In a nuclear apocalypse there’s plenty of necessities: food, water, shelter, clothing. But what would people do for entertainment?

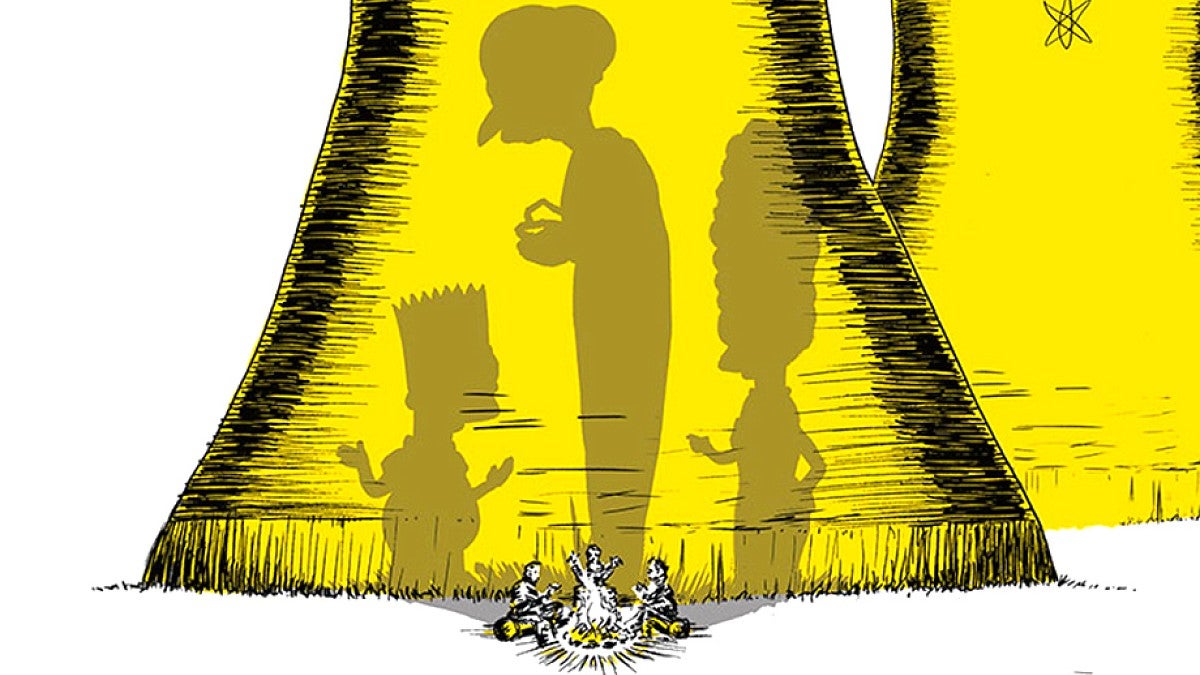

Well, in “Mr. Burns, a Post-Electric Play,” a dark comedy being performed by the UO’s University Theatre in early June, survivors band together and try to re-enact the “Cape Feare” episode of The Simpsons to brighten up the bleakness.

The play fast-forwards seven years, and the episode has become the center point for all pop culture. And in another 75 years, Bart and Lisa have transformed, turned into myths from which new forms of performance are created.

“They start off trying to remember, so it’s pretty close to the actual episode,” said Tricia Rodley, instructor in the UO’s Department of Theatre Arts and the director of the production. “By the time we get to seven years later, more noticeable changes start to happen, and in the third act these are not The Simpsons characters that we know and love; most have merged into more noble tropes. They're recognizable, but they serve a different function.”

“Mr. Burns” premiers at the Hope Theatre in the Miller Theatre Complex on June 1 at 8 p.m. and runs through June 11 at 2 p.m. For all show dates and times, or to purchase tickets, visit the UO Ticket Office’s website. Tickets are $10 for adults, $8 for seniors, faculty, staff and non-UO students, and are free for UO students.

The play was written by Anne Washburn in 2012 and opened at the Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company in Washington, D.C. It was a 2015 Whiting Award winner, which is given annually to 10 emerging writers in fiction, nonfiction, poetry and drama.

Rodley said she chose “Mr. Burns,” which the cast and crew have been working on for more than a year because the issues it addresses are very relevant in today’s world.

“The way the world is going right now there’s a very present fear of nuclear catastrophe in a way there hasn’t been in a while,” she said. “It’s about community and how we respond to disaster together, and the idea of cultural memory — what we remember, what we value, how we try to hold on to that if it’s taken away from us.”

—By Noah Ripley, University Communications