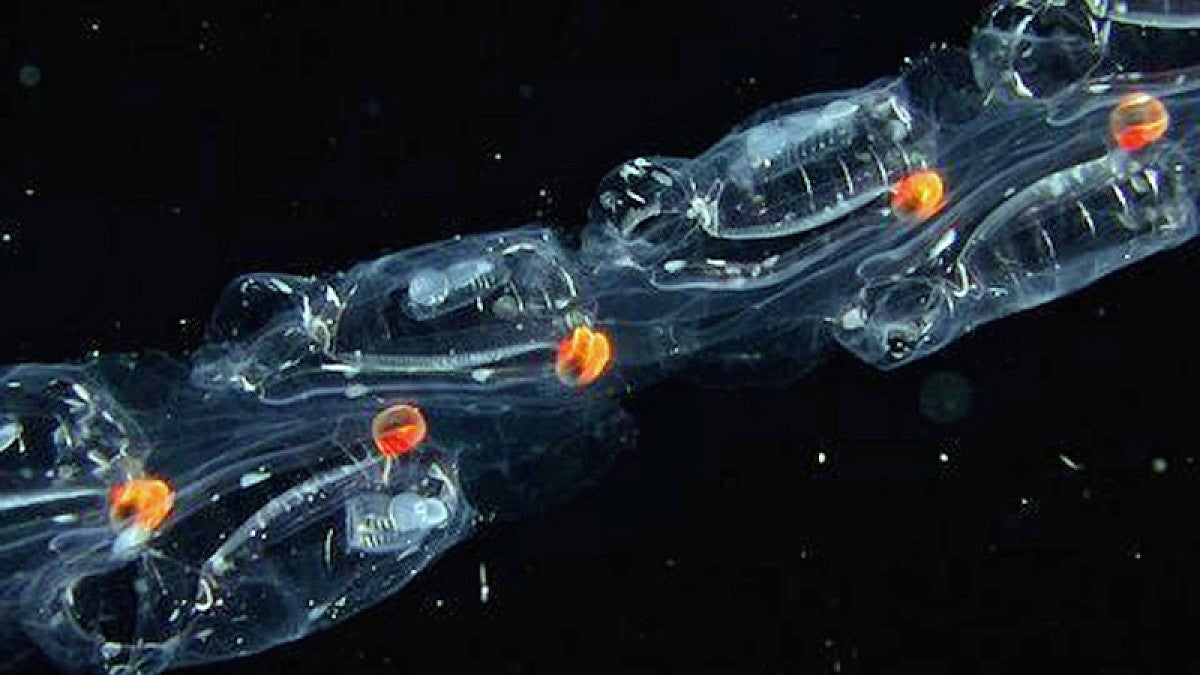

Ever wondered what those clear, jellyfish-like blobs on the beach are? Well, they’re called sea salps, a barrel-shaped organism that swims by using contractions to pump water through its body.

Part of their lives are spent swimming alone, but the rest it is linked with other salps, forming a chain. And it’s while they’re linked that they exhibit the strange behavior discovered by UO marine biologist Kelly Sutherland.

When the salps are faced with a strong current or a predator, they synchronize their propulsions to achieve maximum speeds. But in every-day life, when they’re just swimming along, each salp in the chain swims at its own pace. And, contrary to what might be expected, this translates into more efficient transportation for the entire group.

“The story with a lot of the things I work with is fact is always stranger than fiction,” Sutherland said. “You couldn’t make this stuff up.”

The salps can travel thousands of feet every night — the equivalent of a human running a marathon every day — at speeds around 10 body-lengths per second. Studying their movement can help researchers find new, more efficient, ways to move underwater.

“It can inform design principles and give us new ideas we wouldn’t come up with ourselves,” Sutherland said.

For more, see “It’s Better to Swim Alone, Yet Together, if You’re a Salp” in The New York Times and “Researchers find that teamwork helps jellies jet around the ocean” in Around the O.

Sutherland has been teaching at the UO’s Clark Honors College since 2011. Her research looks at how marine organisms interact with one another and within their fluid environment. She is affiliated with the Institute of Ecology and Evolution and the Oregon Institute of Marine Biology. She also sits on the steering committee of the Ala Alda Affiliate for Science Communication.