In 2017, David Koch was volunteering as an exhibition designer for the United Nations when the organization posted an opening for a museum curator in Ethiopia. Koch had never worked in a museum, held no curatorial degrees, and didn’t live in Ethiopia, but his reaction to the advertisement illustrates his approach to most things in life. He went for it.

Koch (right) credits his experience as a writer and director for high-profile TV clients—HBO, Cinemax, Showtime, the Sundance channel, and PBS—for landing him his first job with the UN in 2003 as a special projects producer and style editor at UNICEF. With the Africa Hall project before him now, he sees nothing less than the culmination of his work for the global agency.

“I applied for this job because of the passion that I brought to my video projects at UNICEF and the success of other communications collateral I produced for the UN,” he says.

Koch is the public exhibition development coordinator for the new visitor center, part of the renovation of Africa Hall, a project at the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (ECA), the UN’s headquarters on the continent. The part-time consultancy sends Koch shuttling between the Ethiopian capital and his home in New York City every few months.

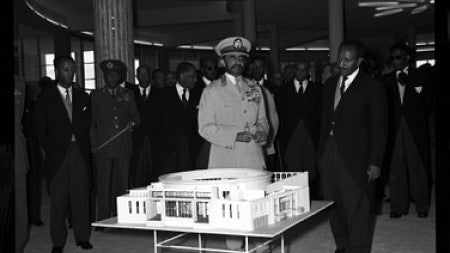

Africa Hall was commissioned by Haile Selassie, Ethiopia’s longtime emperor, and debuted in 1961 as the main conference hall and permanent headquarters for the ECA, established to encourage economic cooperation among member states. At the time, countries across Africa were emerging from the yoke of colonialism; two dozen had obtained independence in the preceding decade.

“Africa Hall was a venue for heads of state, diplomats, and ministers to come together and talk about Africa’s future,” Koch says. “It was exactly what Selassie had envisioned.” In 1963, the Organization of African Unity—the precursor to the African Union, which represents 54 countries on the continent—was founded in Africa Hall, a soaring space with pastel, UN-blue chairs behind tables arranged in horseshoe shape.

Designed by Italian architect Arturo Mezzedimi, Africa Hall sits atop a hill with a view of Addis Ababa’s skyline. The grand building features a façade of glass windows and a balcony stretching the length of the exterior. The “Total Liberation of Africa,” an enormous floor-to-ceiling stained glass window depicting Africa’s past, present, and future, by Ethiopian artist Afewerk Tekle, greets visitors ascending the interior staircase.

“To me, Africa Hall is stunning,” Koch says, while admitting in the same breath that not everyone would concur. He’s a fan of mid-20th century, World’s Fair-era, Cold War–style architecture because it symbolizes a post-World Wars aesthetic of aspiration— for example, the Bauhaus-inspired dedication to can-do modernity. “You just feel the UN’s sense of purpose when you walk through this space,” Koch says. “It’s that idea of bringing member states together on equal footing to build a better world.”

Koch’s task can be summarized in five words: “What does the public experience?” Anything related to that question falls under his purview, and as far as Koch is concerned, the scope is nearly limitless.

Consider the exhibitions. The business plan states that Africa Hall will host permanent and temporary exhibitions—a broad mandate that sets Koch’s mind churning. “Could we partner with the world’s leading museums? Yes, we could,” he says. “What about audio wands with all the UN languages, plus additional African languages? Or perhaps a ‘Model UN’ program? It’s a tabula rasa, and that’s what makes this so exciting.”

Koch is developing a tour program for schoolchildren, architects, international tourists, and university students, in multiple languages and led by highly trained guides. He is also responsible for a video short on the history of Africa Hall, which will play on a giant, state-of-the-art LED screen in the main conference room.

This project draws on skills Koch has honed in prior paid and volunteer positions with the UN.

In 2017, he produced the public exhibition that ran concurrently with the Ocean Conference, an event in New York City focused on the conservation and sustainability of the ocean and seas. The content and media were up to each exhibitor, but the overall aesthetic was Koch’s responsibility. Text accuracy, sign placement, typestyle choices, cohesion among graphics—all these details needed to be accounted for. “It was a great challenge because I was corralling dozens of moving parts into a satisfactory, pleasing, rewarding, and memorable whole,” he says.

Even as a child growing up in Sacramento, Koch noticed the details. An appreciation for his parents’ collection of “faux Scandinavian furniture” helped inspire a European trip during high school. That, in turn, fueled Koch’s wanderlust. He couldn’t wait to leave sunny, hot California for the “rain, pines, moss, and gray skies” of Eugene.

At the UO, Koch felt immediately at home. “I didn’t buy Birkenstocks, I didn’t become a vegetarian, I didn’t really do any of the outdoor things,” he says, smiling. “But I loved it and did become a Birkenstock-wearing vegetarian later in life.”

When he was working on environmental issues for the UN in Nairobi, Kenya, Koch thought it would be interesting to expand his role beyond audiovisual production. As he learned more about the public-facing component of UN-compound sites, Koch wondered who was lucky enough to get to work on those assignments. Now, he is that person. If this is the last role Koch has at the UN before retirement, he intends to go out on a high note.

“Africa Hall really is the project of a lifetime,” Koch says. “I’m putting everything I have into it.”

—By Kelsey Schagemann

Photo courtesy of David Koch