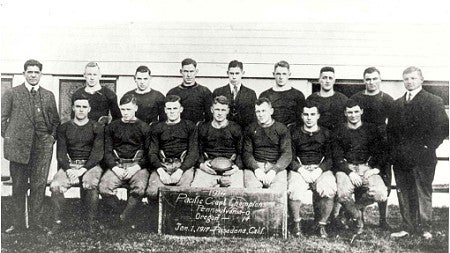

Back in 1917, when the Ducks played in the third-ever Rose Bowl, things were a lot different.

For starters, they weren’t the Ducks. And it wasn’t the Rose Bowl.

The UO was the Webfoots, and the team wore blue and yellow uniforms and played on Kincaid Field, near where the Lundquist College of Business now sits. Justin Herbert would have looked decidedly out of place representing Oregon back then — the Webfoots’ playbook did not include a single passing play.

Meanwhile, Tournament of Roses organizers were in charge of putting together the Tournament East-West football game, which accompanied the beloved Rose Parade. The inaugural game had been played in 1902, and a crowd of 8,000 showed up to Tournament Park on the California Institute of Technology’s campus to see Michigan beat Stanford, after the team from Palo Alto simply quit playing while trailing 49-0.

After that debacle, the game was replaced with chariot races, inspired by “Ben Hur.” When the Tournament East-West game was finally played again, on New Year’s Day in 1916, the Brown Bears took on the Washington State Warriors. The Warriors spent their mornings leading up to the game acting as extras in the silent film “Brown of Harvard”; the Bears relaxed by attending the Rose Parade.

The Warriors won, but unimpressed pollsters declared Cornell, Pittsburgh and Oklahoma national champions. Pac-12 fans think there’s an “East Coast bias” now? At that point, every national champion or co-champion had come from the Ivy League, and the Sooners replaced the University of Illinois as the westernmost team to even share a title.

Washington State’s win failed to improve the West Coast’s standing. One sportswriter dismissed the Bears as only the ninth- or 10th-best team in the East, while the Los Angeles Times wrote that the Warriors’ win “did nothing to diminish the widely held belief that East Coast teams were vastly superior to their Western challengers.”

Something momentous was needed to break the East Coast’s stranglehold on college football dominance.

That “something” turned out to be the University of Oregon.

Playing the role of Goliath to the Webfoots’ David was the five-time national champion Penn Quakers, who boasted a loaded roster featuring four All-Americans. The Quakers were a three-touchdown favorite over the Webfoots, and even coaches who had faced the UO that year picked Philadelphia’s finest to defeat the upstarts from Eugene. As the Oregana reported at the time, “Few dopesters gave Oregon a chance against the well-coached Quakers.”

“We are going to put a team on the field that won't be licked and consequently can't be licked,” Penn head coach Bob Folwell told the Washington Times. The Quakers were so confident that they held an open practice session, where they proudly showed off their dazzling array of trick plays in front of an awed crowd that included the Webfoots.

“I've got only overgrown high school boys, while Penn can field a varsity of big university strength,” said Bezdak. “We haven't a chance.”

When the Webfoots and Quakers arrived at Tournament Park on New Year’s Day, 1917, they were greeted by a raucous crowd of more than 26,000. Back in Eugene, the Heilig Theater on Willamette Street was packed with people wanting to follow the proceedings in Pasadena.

The first radio broadcast of a college football game was more than four years away, so plays were relayed via Morse code a Western Union representative backstage, who passed it along to an announcer who called it out over a megaphone, while the position of the ball on the field was displayed on a board set up on the stage.

What the fans heard, and what the crowd in Pasadena witnessed, defied belief.

The Webfoots’ stellar defense stuffed Penn repeatedly on every drive, including one late in the first half where the Quakers advanced as far as the UO’s 10-yard line, only to be repelled.

In the third quarter, Shy Huntington, the Webfoots’ quarterback, kicker and safety, picked off a pass and led the team on a 70-yard drive back down the field. At the 20-yard line, UO halfback John Parsons handed off to Huntington on a reverse, and Huntington threw the ball to Lloyd Tegart for a touchdown.

“We had been led to believe that they had (no forward passes) at all,” Penn captain Neil Mathews later told the Philadelphia Public Ledger. “We found out to our sorrow that this dope was all wrong.”

Penn’s scouting report wasn’t wrong, though. It’s just that they’d inadvertently taught Oregon that trick play during the open practice session.

“Imagine what we thought and said,” Penn quarterback Bert Bell lamented in a Times interview, “when Oregon scored its first touchdown on our own play.”

Across Oregon, cheering broke out. In the Heilig, hats and coats were thrown into the air in celebration. Newsrooms erupted in delight, with the Klamath Falls Evening Herald later comparing its staffers’ responses to “acrobatic stunts.”

The result was a 14-0 win for the Webfoots, leading LA Times writer Harry Williams to proclaim that West Coast teams would “lick the stuffing out of every eastern team.” Philadelphia’s Evening Ledger called the UO’s victory a “splendid performance,” while a wire report stated West Coast teams were “as good and better than eastern elevens,” and added the UO “is hailed as one of the greatest in the U.S.”

Beckett was named the game’s Most Valuable Player, and was also named an All-American, becoming just the second player from a West Coast school to earn the distinction.

While the Webfoots’ performance was not enough to see the team crowned national champions — that honor went to the Pop Warner-coached Pittsburgh Panthers — it did finally bring national attention to the football played on the Pacific seaboard. Before that game, no West Coast school had won a national championship; in the decade following, Cal and Stanford combined for five. By 1937, 20 years after Oregon’s win, conference schools had won 11.

The school which once fielded “overgrown high school boys” and didn’t play in a single bowl game from 1963-89, is enjoying a period of dominance unparalleled in its history. The Ducks are one of only four teams with multiple national championship game appearances this decade — though LSU and Ohio State University could join that list this year — and no conference rival has more Pac-12 Championship Game wins.

And, thanks to the team that stunned Penn in 1917, the days of those wins being met with deafening silence are long over.

—By Damian Foley, University Communications