On a sunny summer day in Seoul, DaHyun Kim is going over paperwork and preparing for her only clients of the day — a group of young defectors from North Korea.

The recent UO grad will be their guide, bringing them to the United States, and training them for three months to assimilate into a new life. The process is part of her work with nonprofit Liberty in North Korea, an organization that helps refugees resettle in a safe place; provides transportation, clothes, documents, medical checkups and work; and sometimes reconnects them with loved ones.

“Millions of North Koreans have fled the country, but even after they were able to escape through the most guarded border on earth, they are still at risk of exploitation and capture because they cannot afford the journey to a safe country,” Kim said. “Many make it to China, but that country repatriates hundreds back. Others are forced to work illegally and are exploited and abused. Half of our refugees are children.”

Liberty in North Korea works exclusively through donations. It costs $3,000 to rescue one refugee and set them on a path to a new and safe life. So far, the organization has assisted more than 756 North Korean refugees.

In August, Kim will return to the U.S as a project coordinator at Liberty in North Korea, which has its headquarters in Los Angeles, teaching young refugees English, training them in public speaking and working with local media to tell the story of young North Korean defectors.

Ironically, Kim’s own personal path had plenty of obstacles, and despite the empowering and courageous work she does today, she wasn’t always so sure of her own future.

Kim is a survivor of domestic violence and was raised by a single mother and moved a lot during her childhood. She was born in Bucheon but lived for a long time in Suwon, in northwestern South Korea. Her mother happily remarried before the family finally settled in the town of Daejeon.

“Growing up, I never knew what I wanted to do,” Kim said. “I never thought I was good enough for anything. I grew up by myself. My mother was always working, like, 20 hours a day as a hair designer, server and cook. I had no support or care at home. I just thought I would become whatever my mom would tell me to be.”

As a teenager, Kim had low hopes for herself. When given the opportunity to learn English at school, she didn’t care for the class because she never imagined leaving South Korea.

“The idea of going to Oregon didn’t come to me until the last year of high school,” Kim said.

Kim’s mother contacted her only sister, who has lived in Salem for more than 30 years. The aunt sponsored Kim for a visa so she could attend Chemeketa Community College and learn English.

In March 2011, three months after graduating from Banseok High School, Kim arrived to an unseen Oregon with one suitcase, no English skills or experience of another culture, and $5,000 — her mother’s life savings.

After a term of English courses, Kim transferred to Portland Community College. As a student worker at PCC, she worked a lot with the international students office. That experience and her work as a student ambassador sparked an interest in international studies.

In fall 2015, Kim transferred to the UO, having earned a scholarship through the International Cultural Service Program. She served as a student ambassador promoting Korean culture and participating in discussions of international issues across campus.In February 2017, Kim earned a grant for a six-month professional media internship at the United Nations headquarters in Nairobi, Kenya. The trip would prove a catalyst for her international career and an eye-opening experience on the kind of work she would end up doing.

“From the moment I got to Kenya, I wanted to see how people lived,” Kim said. “From the moment I landed, I was very excited.”

But as Kim found out, once diplomats, visitors and interns arrive in Nairobi’s Green Zone, they are advised not to leave the area without a security escort, and some areas of the city are forbidden to U.N. visitors.

As the first weeks went by, Kim met a lot of diplomats and officers at the U.N.’s environment headquarters. She even met U.N. Secretary-General António Manuel de Oliveira Guterres.

However, she felt unsatisfied with the experience.

“At the time I wanted to go out and deny all of the bad media I had seen about Kenya,” said Kim. “But every official simply scared me with ideas about going out of the green zone.”

Kim shared her frustrations with a German graphic designer in the office named Viola Kup. She didn’t know Kup was also the founder of Usanii Lab, a graphic design collective that teaches practical design skills to youngsters in the slums as a way to overcome poverty.

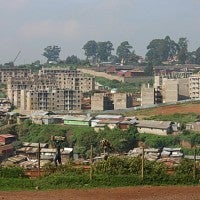

Kup snuck Kim into Mathare Valley, a slum east of Nairobi that is home to more than 500,000 people and is one of the oldest slums in Africa.

“They train the kids to learn photography, how to use Photoshop and do graphic design,” Kim said. “Once they are done, they recruit a new cohort and have the former team teach the same skills to newcomers. Along the way, hopefully they raise a little bit of money to keep the whole thing going.”

But Kim soon found a harsher reality in Nairobi. Her homestay mom, Anika, was a volunteer at local orphanage, Toto Angel Centre, and around the middle of her stay in Nairobi, Kim once again snuck out of the U.N. safe area.

This time it was to visit the orphanage in a town named Buruburu, an area known to have one of the highest numbers of gangs in Kenya.

“Most of the children in the orphanage were born in the town, but their parents simply cannot afford to take care of them,” Kim said. “Instead of seeing their kids suffer, the parents send the children to the orphanage to get a meal, learn something and play. The sad part is you cannot take out the orphanage out of the city and at the same time it is surrounded by violence.”

The experiences of a single place with different needs made an impression on Kim and shaped her professional agenda to become a social problem solver, not a diplomat.

“I think everyone needs someone who believes in them,” she said.

Kim left Kenya and returned to Oregon in fall 2017 to complete her bachelor’s degree in international studies and a minor in economics. She graduated last spring.

Looking out of the window of her office, DaHyun Kim seems to reflect on much of what has happened in her life. But quickly she turns to the task at hand. She shuffles a few folders in her hands and straightens them up, ready for her clients.

A smile on her face, a streak of light comes through her window.

—By Chakris Kussalanant, University Communications