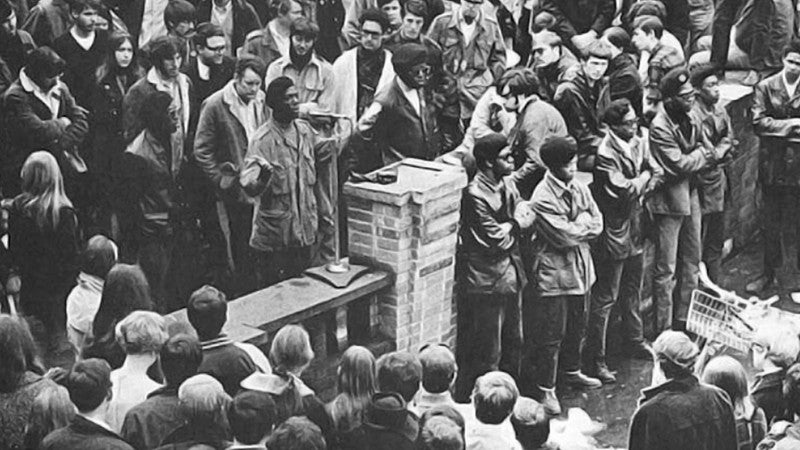

On April 8, 1968, while the country was mourning the assassination days earlier of Martin Luther King Jr. and racial tensions mounted nationwide, the Black Student Union at the University of Oregon issued a list of grievances and demands to then-President Arthur Flemming.

Among those demands was campus space for black students and other minorities to gather and have access to tutoring and a place to study.

Flash ahead to Nov. 12, 2015, and unrest was once again simmering on campuses across the nation in connection with protests at the University of Missouri around acts of racism. Students at the UO held a march in solidarity — one of dozens around the country — in support of their counterparts at Missouri.

The events of that day set fire to a movement that first flickered 50 years prior and would result in a building dedicated to the needs of black students on campus: the Lyllye Reynolds-Parker Black Cultural Center.

The center celebrates its grand opening Oct. 12, one year to the day after groundbreaking. It will serve as an academic and cultural touchstone for black students. Programs and resources will now be at hand to help them more successfully navigate their path through the UO.

Named after Reynolds-Parker, a popular and beloved student advisor with a long family history in Eugene, the center will be open to all students who want to learn more about black history and culture. What’s more, the center, which sits on East 15th Avenue between Moss and Villard streets, will serve as a gathering place for future, current and former students.

It was designed to provide flexible space that can accommodate an array of activities, including study, student meetings, academic support and even small classes, dinners or performances and will showcase cultural pieces and artwork that celebrate black heritage.

Desirae Brown, a senior sociology major and co-coordinator of the Black Women of Achievement student group, has been hearing about the center since she set foot on campus.

“It’s important for me because it’s going to be the only space on campus that was built with me in mind and my needs as a black student,” Brown said.

A long history

The heading reads: “Grievances and Demands of Black Students on the University of Oregon.”

The seven-page document, dated April 8, 1968, and signed by Johnny Holloway, president of the Black Student Union, lists four grievances and five major demands. The demands included adding more black dormitory counselors, increased financial aid and the addition of African-American curriculum.

And under the “General” heading, item D lists: “That office space and adequate facilities be provided to the Black Student Union in order to conduct a study skill and tutoring center.” Flemming established a “committee on racism” to research the students’ grievances, according to coverage in the Eugene Register-Guard from the time.

The creation of that space took a meaningful step forward on Thursday, Nov. 12, 2015.

Shortly after the conclusion of a lecture by Charles Ogletree of Harvard Law School on “Black Lives Matter: Race and Justice Across America” at Ford Alumni Center, a long column of marchers progressed along East 13th Avenue toward Johnson Hall. A group of students that would form the core of the Black Student Task Force organized the march as part of a nationwide action in solidarity with events in Missouri, sparked by the Black Lives Matter movement as well as issues of race and a hunger strike at the University of Missouri.

The UO marchers also seized the moment to express frustration and anger about racism and other concerns on their own campus. With President Michael H. Schill walking alongside the marchers for part of the route, they gathered in front of Johnson Hall where students took turns on a megaphone airing their concerns.

Afterward, many of the marchers and others gathered and drafted a list of 12 demands, one of which included the opening of a black cultural center. Members of the newly formed Black Student Task Force then met with Schill, where they delivered him their list of demands.

Task force members worked behind the scenes on the center. They were closely involved in planning and building support for it, including visiting key donors.

On Jan. 25, 2017, thanks to a lead gift from longtime university donors Nancy and Dave Petrone, their efforts took a major step forward when Schill announced he would recommend the construction of the Black Cultural Center.

Under sunny skies on Oct. 12, 2018, attendees overflowed outside tents erected for the center’s groundbreaking ceremony.

The speakers included several of those who formed the Black Student Task Force back in 2015. Alumni, students, faculty members and community members beamed as shovels broke through the soil and the much-anticipated project got underway. Many described the day as “historic.”

A turning point

Yvette Alex-Assensoh, vice president for equity and inclusion and professor of political science, is one of the people who was there from the start, who helped nurture the Black Cultural Center from idea to reality.

Serving as a liaison between the Black Student Task Force — which included Shaniece Curry, Dayja Curry, Denisa Clayton, Mimi Gomalo and others — and the UO administration in the days following the 2015 march, Alex-Assensoh helped design and lead the working groups that looked into each of the task force demands. She was involved in initial discussions about the cultural center, helped form a committee led by Jamie Moffitt, Robin Holmes and members of the task force to investigate its feasibility — what will take place inside of the center — and then played a pivotal role in fundraising for it.

She believes its impact will be monumental.

Alex-Assensoh said that the center represents a physical place of belonging for black students on a campus that has few markers regarding the positive contributions of black people and other people of color.

“More importantly,” she added, “it will serve as a site that ignites imagination about endless possibilities for unlimited academic success at the university and as impactful leaders in the world beyond.”

A transformational space

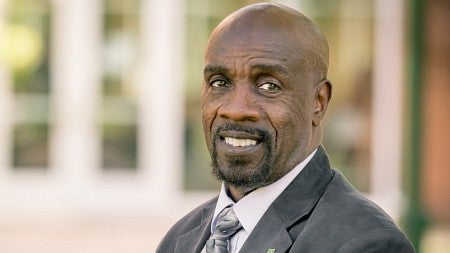

In his office on a September afternoon, Kevin R. Marbury, vice president for student life, proudly held up the plaque that will accompany the time capsule to be placed inside the Lyllye Reynolds-Parker Black Cultural Center.

It will be one of the final pieces to a project whose roots reach back 50 years.

“Of the 12 demands, I really thought the creation of the Black Cultural Center was probably the furthest down the road,” he said. “There were so many other things that were going to have to happen.”

Marbury was hired by the university in 2012 to help oversee construction of the new Student Recreation Center. He was planning on sticking around for about four years, but then things changed. He was asked to help take part in work with the Black Student Task Force and committees researching the list of demands.

“They played a huge role,” Marbury said of the task force members who helped get the center built.

“There was a lot of momentum going, and through that gift we were able to maintain that,” he said. “And here we are ready for a grand opening of something that is going to be transformational for this campus, this community, for the state. I’m really proud of all the people who sacrificed time and money and energy to get us to this point.”

The opening will be a powerful moment for Marbury.

“I’ve been involved in a lot of projects throughout my career, building things, building programs, but this one’s really, really special,” he said. “I think about those students in 2015, standing out in front, saying ‘See me, pay attention to me.’ But then going back 50 years before that to that group in 1968 saying the same thing, the persistence is inspiring. For the University of Oregon to finally say, ‘Yes, this is something we need to do,’ I’m just ecstatic to be part of it and whatever role I was able to play.”

A great opportunity

Marcus Langford had just returned from one of the final walk-throughs of the Lyllye Reynolds-Parker Black Cultural Center, which was slated to be handed over to the university in just a few days. While much work has been done, more lies ahead, the associate dean of students said.

Along with Aris Hall, the building’s new coordinator who started Sept. 30, Langford will help shape the academic programming that happens within the center.

The first year will be about developing connections between faculty members, student organizations and other groups. Langford said the center is planning on offering events such as cultural enrichment programs, skills and leadership development workshops, or inviting faculty members for tutoring sessions, study tables, review sessions and possibly classes.

“Those are some of the ways we can ensure that the Black Cultural Center is leveraged to enhance the academic success of our black students,” Langford said.

He also wants it to be a welcoming gathering place for students and others to enjoy.

Langford expects the build-out of the center’s programming to be an intentional and incremental process. And he recognizes that many people have high and varied expectations for the center and its coordinator. That’s kept him up at night, but it also energizes him.

“Part of what I’m most excited about is what this means for students on the front end who invested a lot of time energy and effort into this,” he said. “I’m pleased they will have the opportunity to see the results of all the time, energy and effort they expended.

“I’m also excited about what this means for students who are here and those who will be coming behind,” he added. “I think this is an awesome opportunity — something that I genuinely believe will serve black students at the University of Oregon well, and as a result of serving black students at University of Oregon well, it will serve the University of Oregon well.”

Building a foundation

Ericka Warren sees opportunity that she never had when she looks at the Black Cultural Center.

When Warren, a 1992 grad, was on campus, the gathering space for black students was unimpressive.

“The Black Student Union office was a little small corner in the basement of the EMU,” said Warren, who is now president of the Black Alumni Network. “It did not allow for the opportunities that will be presented to students going forward.”

As the idea of a Black Cultural Center began to take hold, Warren and other members of the Black Alumni Network rallied in support, raising money for a resource they would have loved to have had access to when they were here.

“This is a place where students who are coming onto this campus can feel a sense of home, can begin to build a sense of community,” Warren said.

But like others, Warren sees the center as a foundation from which to build rather than as a finish line.

“This is a great place for us to begin,” she said. “I want to celebrate the tenacity and courage of the Black Student Task Force. They did an excellent job echoing the sentiments of the 1968 BSU members, and they were persistent. They were engaged, they brought their needs before the university and engaged with us as the Black Alumni Board. We are so pleased that President Schill was open and listened.

“I hope that the BSU students from 1968 are proud of the seed that they planted, and I hope that they’re filled with sense of accomplishment as well,” she added. “I hope that the greater community at the University of Oregon — students that are not students of color — I hope they learn to embrace this as well and see it as something positive, that they’re part of a campus that appreciates diversity and celebrates inclusion. I hope that alumni take the opportunity to reconnect through the BCC and give back to students in the way they would have loved to have been embraced when they were undergrads.”

With some of the 12 demands remaining unmet and with the center still in its infancy, Warren echoed a theme aired by many.

“Now the issue is, how do we move forward. How do we best utilize this space to create an inclusive community on campus,” she asked.

More than a building

The Black Cultural Center sits on the eastern edge of campus, near the Global Scholars Hall and other student housing in the East 15th Avenue and Villard Street neighborhood.

The 3,200-square-foot, $3 million center is being funded mostly by private donations, led by the Petrones. Operations of the center will be funded through the president’s strategic investments fund.

In college, Marbury was part of only the second group of students to live in a black cultural center at the school he attended as an undergraduate, so he understands some of what the students here might be feeling and knows the building is only part of the equation.

“It wasn’t so much what was inside the center, it was what came out of the center, the interactions and the experiences you had in the place and how they manifested themselves when you left,” he said, adding that he expects a similar effect here.

“Lots of people are going to be overwhelmed by what comes out of just 3,200 square feet of space,” he said.

For current students, like senior Desiree Brown, it represents progress and hope.

“I want it to be a space where I can see other black students using it in a way that makes them feel welcomed on campus,” she said. “I think creating that space for black students will help bring energy to campus as a whole. It will make it better.”

—By Jim Murez, University Communications