Editor’s note: This article is republished as it appears in The Conversation, an independent news publisher that works with academics worldwide to disseminate research-based articles and commentary. The University of Oregon partners with The Conversation to bring the expertise and views of its faculty members to a wide audience. For more information, see the note accompanying this story.

Imagine you’re in line at a coffee shop. You order your usual cappuccino and swipe your credit card to pay. Then the cashier swivels a little screen that prompts you for a tip – before the espresso shot is pulled or a drop of milk steamed.

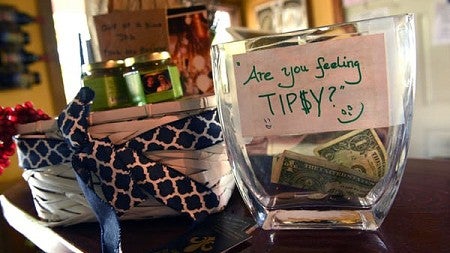

This is a dilemma that most of us are increasingly facing in a variety of settings where previously you might have encountered a lone tip jar with change and crumpled dollar bills. Now we’re being asked to fork a over $3 tip for a $4 coffee drink.

In recently published research, we explored how this new preservice tipping etiquette is affecting consumers, and what it meant for the baristas and other employees hoping for a reward for their efforts.

The pre-service tip invasion

Point of sale platforms such as Square and Clover are making it easier than ever for businesses large and small to seamlessly integrate tip requests into the service experience.

While most of us are used to filling out the tip line on a receipt at a full-service, sit-down restaurant, we are now seeing tip requests occur in many new environments, such as cafes and bakeries, fast-casual delis and food trucks, and even retail stores, flower shops and liquor stores.

Articles in the popular press about the trend suggest that some prefer the convenience of tipping when placing their order. Others say they feel that they are being guilted into tipping employees who have not yet provided a service and who have done little more than type in an order and hand over a muffin.

How consumers really feel about it

To find out how people respond to differences in tip timing – before or after service – we conducted a series of experiments with fellow marketing professor Hong Yuan.

We looked at how it affected tip amounts, ratings and likelihood of returning to the business, controlling for variables that might affect tip amounts, most notably the effects of repeat customers or attractive workers.

Next, to dive a little deeper into why, we conducted three experiments in which we recruited participants online and asked them to imagine themselves a customer in a scenario. In one, participants imagined ordering a drink and a sandwich at a cafe, while the other two involved getting a haircut at a salon. In all three, participants were randomly prompted to tip either before or after receiving service.

Then we asked them to fill out a scaled survey rating the experience in terms of how likely they’d be to return to the business and how they felt about the tip request. In the third study, we also asked participants to select how much they’d tip and and how they’d rate the service on Yelp.

In each study, we found that participants viewed preservice tip requests as unfair and manipulative and reduced the likelihood that they would become repeat customers. In the third study, requests for tips before a haircut also led to lower gratuities and online ratings.

We also found that businesses that emphasize the convenience of tipping can offset some, but not all, of the other negative feelings.

Tip benefits

Tipping trends are constantly shifting.

Some innovations include the introduction of recommended tip amounts on receipts and the proliferation of tip jars in the 1990s and most recently digital tip requests. Each has contributed to “tip creep,” which has pushed up the average tip from 10 percent in the 1940s to more than 20 percent today and made tipping the norm in more and more types of business.

Our findings, however, suggest that businesses should be careful when adopting new innovations. Customers, employees and owners all benefit if businesses stick to tradition and request the tip only after the coffee is poured.

—By Nathan B. Warren, University of Oregon, and Sara Hanson, University of Richmond