Combating Racism

February 2022

At the UO, as across the country, we have had to face a renewed reckoning around issues of race and inequality. We know the work of creating a more inclusive and antiracist community is a continuous journey. Each month, these pages will highlight some of the work being done and the resources available here on campus. We hope these efforts act not as a token, but as a turnkey to help open doors for those to come.

Carina Miller, Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs (Photo by Anna Glavash Miller)

Rachel Cushman, Chinook Nation (Photo by Amiran White)

A Spirit of Service

Young professionals, young mothers, and busy UO alums, Rachel Cushman BS ’10 and Carina Miller BS ’11 also find time to serve their Indigenous communities as elected leaders.

The University of Oregon is located on Kalapuya Ilihi, the traditional Indigenous homeland of the Kalapuya people. Following treaties between 1851 and 1855, Kalapuya people were dispossessed of their Indigenous homeland by the United States government and forcibly removed.

In the present day, the state and university have begun taking steps of coming to account with still-painful aspects of our histories. Cultural institutions are challenged to make amends and restore sound communal relations not only with the descendants of the Kalapuya, but with all of Oregon’s diverse Indigenous peoples.

“The educational system as it exists today was instituted to erase us,” says Rachel Cushman, BS ’10 (ethnic studies). “Indian people who are living today all have been traumatized by the white colonialist structure, and in places like the UO we still have to take up space and find a way to belong.”

Since graduating in the first UO cohort to earn bachelor’s degrees in a department-housed ethnic studies program, Cushman—who uses the gender-neutral Chinuk Wawa pronoun yaka—has become a spouse, mother, educator and community leader. Recently, yaka has also returned to campus as a first-year doctoral student in the Department of Indigenous, Race, and Ethnic Studies.

“Academic programs like mine exist to undo some of that legacy of erasure and trauma. We educate in order to help deprogram and decolonize.”

Carina Miller BS ’11 (ethnic studies), who grew up on the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs’ reservation, was Cushman’s roommate, confidant and frequent collaborator during their time as undergraduates. For people raised in close-knit Tribal communities, she believes, leaving home for college can be particularly traumatic. Beyond feeling homesick, Miller remembers much of her college experience in terms of culture shock and struggle—especially during the first year.

“Honestly, the hardest lesson the UO taught me was in not being as different as I’d hoped it would be. The same kinds of racism I’d endured in high school, I also experienced in college. But the friendships are what taught me the most. They gave me the support and the ability to look at different viewpoints.”

Reconnecting with her inner resilience, Miller began taking on roles in student governance and organizing. She was elected an ASUO student senator and served as co-director of the Native American Student Union.

“I was raised by my parents to be a leader. But it was a struggle trying to understand how to represent people of color well, not just be tokens and show up.”

Cushman adds, “Multicultural Center Student Unions in the EMU are where I found most of my support in the institution. It wasn’t just the Native students—it was all the students of color working together and building coalition with one another.”

According to yaka, programs like the Sapsik’ʷałá Teacher Education Program and the Critical and Sociological Studies in Education doctoral program took root from students’ social and institutional justice activism.

“We had to fight in many arenas, taking over spaces on campus and making change. It took a lot of student demands even to get the UO where it is today.”

This activist mindset was something that each carried with them after graduating. Even as they pursued careers and took on the many responsibilities of motherhood in subsequent years, both felt drawn in a spirit of service to their people. Eventually, this led them to seek—and win—elected offices.

Cushman currently serves on the Chinook Indian Nation Tribal Council as secretary-treasurer.

“A major goal of mine, as is a goal of all our council members, is clarification of our Federal status,” yaka says. “We need this to ensure our inherited rights are upheld by the U.S. government.”

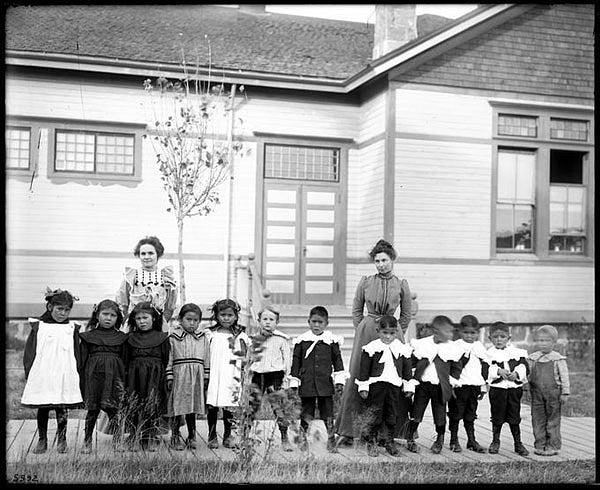

Rachel Cushman’s grandmothers, Jenni and Louisa Lane in photographs taken at the Indian Village in Seaside, Oregon. Courtesy of R. Cushman.

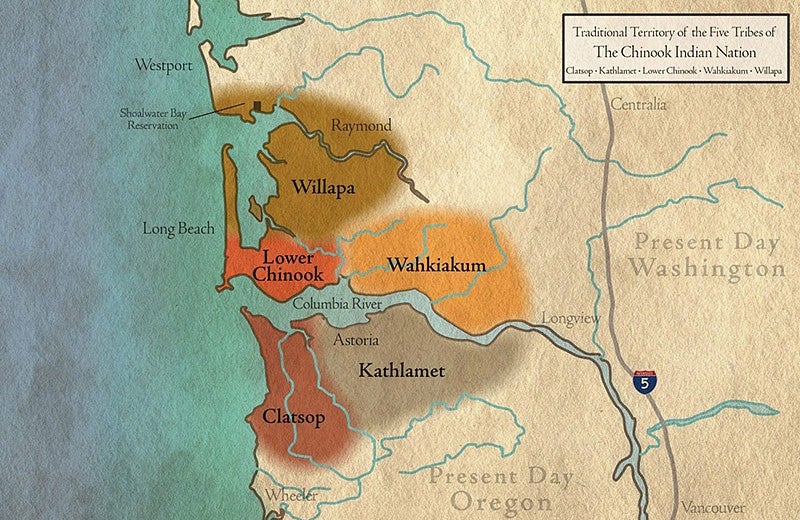

Representing the five Indigenous Tribes with homelands nearest the mouth of the Columbia River, the Chinook Nation has been locked in a struggle for recognition since the U.S. Congress failed to ratify the Tansey Point treaties negotiated by their leaders in 1851. In arbitrary and outrageous contradiction to Oregon’s territorial charter of 1848—pledging that the government would always deal with Natives in good faith and never seize their lands without consent—the five tribes were denied a reservation, annuities, or any other legal benefits of treaty status.

The implications, Cushman recounts, have been enormous. Without Federal recognition, current members of the Tribe were ineligible to receive enhanced health-care benefits extended to most Native Americans during the COVID crisis. Their history is not addressed in Oregon’s K-12 curriculum, which was only designed to cover the state’s nine Federally-recognized Tribes. And as a teenager, Cushman suffered through the heartbreaking withdrawal of a prestigious Gates Scholarship offer after the Chinooks’ recognition—finally bestowed by the Department of the Interior in 2001—was controversially rescinded just one year later.

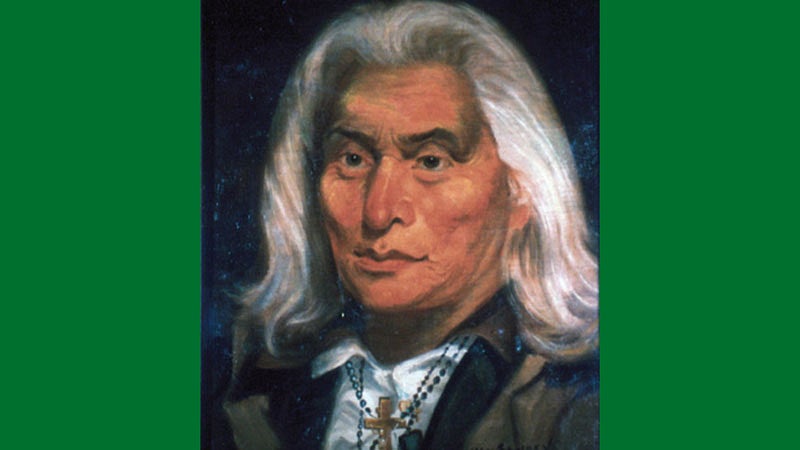

Courtesy of the Chinook Indian Nation

Courtesy of Maximilian Dörrbecker (Chumwa), Wikimedia Commons.

- According to archaeologists, human presence in the Pacific Northwest goes back at least 12,000 years. (“Time immemorial” is the term preferred by many Indigenous people.)

- At the time of their expedition, Lewis and Clark estimated the total population of the Oregon Country at 50,000—we now know the number was much greater, perhaps by a factor of ten.

- Pre-contact Oregon was not only populous, but highly diverse. Scores of languages and dialects representing 13 major linguistic families of North America were spoken here.

- While the vast majority of Indigenous place names were violently erased by white settlers, many rivers and valleys in western Oregon still bear the names of their original inhabitants.

- Of the 109 Tribes and bands terminated nationwide during the 1950s, 62 were in Oregon.

Miller says, “Relationships like the one I have with Rachel have shaped my point of view. Now it also takes into account Rachel’s Tribe; it’s not just about my Tribe and our story.”

Though the community includes the easternmost speakers of Chinookan language, Warm Springs has a very distinct history from Cushman’s people. In 1855, the Wasco and Warm Springs tribes negotiated treaties relinquishing 10 million acres of their traditional lands to the United States, but preserving 640,000 acres for their own use. These lands still comprise the largest Indian Reservation in Oregon. Paiute people later joined the confederation, and Warm Springs has been governed by a representative Tribal Council since 1938.

“We are one of the two Treaty Tribes in the state. We’ve never been terminated and we have a really strong political history.”

But Tribal politics are complex, Miller explains, and not always in the ways that outsiders might imagine. After growing up on the reservation and going off to college, she found that her point of view had evolved in ways that couldn’t be ignored.

“Having an ethnic studies degree, you can’t help but deconstruct things. Going back to your Tribal community after you’ve been educated, you also can’t be quiet.”

She worked for her Tribe in child protective services and head start education, but memories of her student activism and campus coalition-building soon inspired her to seek a more active role in governing the community. She also wanted to provide a voice for some controversial issues.

“I ran for Tribal Council in 2016 on a platform centered on cannabis,” she explains, pointing out that, unlike most of Oregon, possession remains illegal at Warm Springs to this day.

“I was raised in a traditional household, but in my campaign I was also very vocal about our gender roles, healthcare issues, and other things in our community that are harmful. Like a lot of people, I was shocked when I won that election by six votes.”

Since completing her term on the Tribal Council, Miller has run for statewide office, serves on the Columbia River Gorge Commission, and worked to pass and implement Oregon Senate Bill 13, establishing a tribal curriculum for the state’s K-12 public schools, and Oregon House Bill 2845/2023, creating ethnic studies standards.

“We still need to move from a mindset of just teaching about the history of the Tribes,” she says, “to thinking critically about Indigenous perspectives on issues of today, like gaming revenue, natural resources management, healthcare and Federal recognitions. Native youth need to have access to public education that teaches the lessons I got in college at an earlier age.”

Looking ahead to the next steps in the PhD program, Cushman says, “I was a first-generation undergraduate, and I am a first-generation graduate student. My scholarship includes writings about identity, Federal Indian policy, BIPOC resistance to settler-colonial institutions, environmental justice, intersectionality and more. Outside of our classrooms, many of our students would never be exposed to work like this. It’s important because it gives us a little more visibility.”

--By Jason Stone, University Communications

Resources

Visit these resources—a small sampling of the many on campus—for ways to listen, learn, and act in the fight for social justice