University of Oregon junior Miles Sisk considers the Erb Memorial Union his second home. A member of the facilities staff since the summer before his freshman year, he knows every tucked-away corner and stairwell in the 64-year-old structure. He rattles off facts about the building and its history as if he had lived them—the leaks in 2006 that caused the wood floors to buckle three feet high; the inefficiency of the 1970s addition (70 percent of the EMU’s heating costs, he says, went to heating that part of the building); the barbershop that used to be on the ground floor. He takes visitors on a trek through narrow corridors and back stairways to the building’s rooftop. He’s familiar with the underground warren of tunnels that were once used for electrical wiring and steam piping. It gets hot in the tunnels, he says. Very hot. “It’s a little place we call Hell.”

From its earliest conception in the 1920s, the EMU was envisioned as a place for students to congregate; to study, relax, recreate, and participate in student-run organizations. Despite a two-and-a-half-decade gestation before a brick was ever laid, at least one misguided renovation, and an ever-evolving student culture, the vision has succeeded. Not only have the building’s larger spaces served as central meeting areas, but its smaller spaces—tucked away lounges, secluded meeting spots, and upper-level balconies—have served to comfort, nourish, and support thousands of students, and many employees, over the years.

Byron Caloz ’81 says his most resonant memory of the EMU is riding his bike along that very corridor. “Clickety-clack, clickety-clack, as I let the bike tires roll down to the basement-level bricks and then up to the street corner,” he posted on a UO Facebook page. “The EMU was really the heart of the University of Oregon. It told me the university was a great place . . . and continued to reinforce that opinion throughout my time at the UO, not only because of its grand staircase, the bike route underneath, and the Fishbowl, but also because of its many programs which opened up possibilities for students to live and grow beyond what could be taught in classrooms.”

The early days

The EMU that opened in September 1950 was the product of a combination of vision, planning, delayed hopes, and patience. Eagerly supported by the university’s fourth president Prince Lucien Campbell and the classes of 1923-25 the likelihood of a student union at the UO faded after Campbell died in 1925 and subsequent administrations chose different priorities.

Donald Erb, the university’s seventh president, took office in 1938, and according to the 2013 video Meet You at the S.U., Erb revived the dream of a student union, seeing it as a place that would accommodate veterans as well as “a place to practice democracy.” Erb’s advocacy was steadfast, but after the 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor, plans for a student union were once again put on the back burner. No new buildings were constructed during the war years. When the conflict wound down, however, the UO’s enrollment more than doubled as a flood of vets returned to campus, and the need for a student union became undeniable.

Students caught the wave of renewed interest, forming a Student Union Committee in 1944. The following year, the university approved a plan for the construction of a student union to be financed by student fees and outside donations. The State Board of Higher Education gave the plan the go-ahead, preliminary plans were drawn up by 1947, and the UO’s largest fundraising campaign to date—led by alumni Ernest Haycox ’23 and John MacGregor ’23—was soon underway. Ground was broken in 1948 for the new building at the corner of 13th Avenue and University Street—formerly the site of a two-story farmhouse built by pioneer Fielding McMurry, whose brick-making business had supplied bricks used in the construction of the UO’s first two buildings, Deady and Villard Halls. The student union building was completed two years later, at a cost of $2.1 million. It was named for Erb, who had died in 1943, and dedicated to all students who had served in the armed forces.

The structure was unique for the times, says Gregg Lobisser, assistant vice president for capital projects in the Division of Student Life. “It was pushing the envelope of design. The broad expanse of glass in the Fishbowl, that arc of glass, was really out there. It represented a leap forward in modernism.”

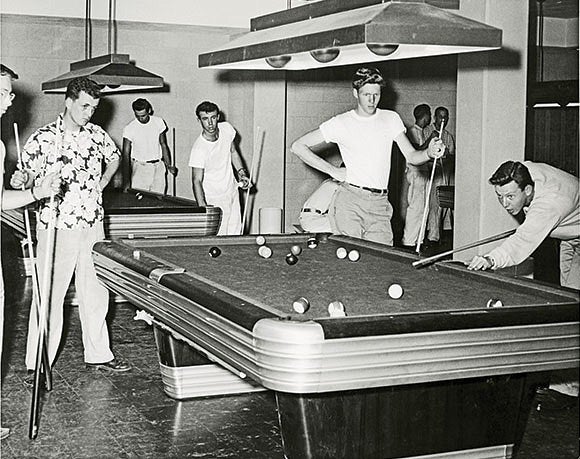

In addition to its modern aesthetics, the union offered students a host of amenities. The ground floor included a four-chair barbershop, a post office, an eight-lane, state-of-the-art bowling alley (25 cents per person per lane before 6:00 p.m., 30 cents after); 10 billiard tables (60 cents per hour before 6:00 p.m., 75 cents after); and seven Ping-Pong tables (15 cents per hour). In the bag-lunch room, students could rent a locker for 10 cents a term to store lunches they brought from home. Two listening rooms allowed students to listen to classical or jazz recordings. Budding pianists could hone their skills in the piano practice room. The building quickly became the center of student activity for the burgeoning campus community.

In the ensuing years, a room was made available for the ASUO president to live in on the building’s third floor. Even though his digs were small, Henry Drummonds, 1966–67 ASUO president, was delighted with them. “I got to live in the student union over the summer. I thought that was pretty cool,” he says. He could come and go as he pleased, but at the time, the university imposed strict curfews on residents of the women’s dormitories. One of Drummonds’s goals as president was getting rid of the curfews. “As a politician, I wanted [the university] to come out of in loco parentis,” he says. “And I was successful.”

The student government offices were eventually moved to the ground floor of the EMU. Emma Kallaway, 2009–10 ASUO president (with Getachew Kassa), says a small closet outfitted with a table and a couple of chairs in the student government office was hugely important to her tenure as president, and to her growth as an individual.

“We called it the ‘situation room,’” she says. “It’s where we would go to have private disagreements with each other. It’s silly, but it was important to have a place where you could disagree in private, and find a resolution without fighting it out in public. It was there I learned how to be wrong, how to be persuaded, how to speak my mind, how to fight respectfully. I learned how to strategize there.”

Another spot that sticks in Kallaway’s mind is the balcony area outside the ballroom. In March 2010, vandals broke into the university’s Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer Alliance office, destroyed its computers, and spray-painted a swastika on the carpet. That night students organized a vigil, and Kallaway went to the balcony to get a bird’s-eye view of the crowd. “People and candles filled the amphitheater and spilled out onto 13th Avenue,” she says. “I saw faculty, administrators, students, and people from the community. I realized I got to live in a place that was kind, that was going to show up when a portion of our community was down.”

The ballroom

In the building’s original conception, the ballroom was intended to be the heart of the EMU. From the lobby, students walked up a grand staircase made of green terrazzo to a room that could accommodate a thousand people. The sprung dance floor made dancing easier on the feet, and students took advantage. Throughout the 1950s, the ballroom was a focal point for social activities—from big bands to student-hosted parties.

Suzanne (Brouillard) VanOrman ’61 had her first volunteer job at the EMU playing jazz records in the listening room. Her second was selecting movies for Sunday afternoon screenings in the ballroom. She remembers a toga party EMU staff members held in the ballroom to thank volunteers. “We all dressed in sheets. Si [Ellington, the EMU director] had a wreath ’round his head. It was crowded and there was a lot of good food.” The party raised eyebrows and created a bit of a buzz. “I’m not sure if they ever had another one,” she says.

The ballroom was used for more serious matters as well. When John F. Kennedy and his brother Ted Kennedy came to the UO, they spoke at the ballroom. “Whenever JFK came to Eugene, we were with him,” VanOrman says. “We were the young people handing out the pamphlets. And when he was on stage, we got to sit with him.” Ted was younger and more personable than his brother, she remembers. “He was the one that connected better with the kids because we were more his age. John was more serious. He was running for president, after all.”

Mike Kraiman began working in the EMU in 1978 and never left. Today he’s the technology administrator and scheduler for the building, but the ballroom is the area closest to his heart. “I’ve spent a lot of my life there. The ballroom is my space,” he says. In the late ’70s, the ballroom was one of the few venues in Eugene where music groups could perform for large audiences, and his job was to manage lights and sound during the shows.

Kraiman eventually mastered the lights, and the sound. He began keeping files on the various groups who performed in the ballroom—Los Lobos, R.E.M., Talking Heads, the Ramones, Dennis Quaid and the Mystics, even a surprise performance by Bob Dylan. Kraiman still remembers Iggy Pop’s gig in 1983, when the rocker threw the microphone stand into the crowd, along with pieces of raw chicken.

For the past several years, the office of Laura Fine Moro, a contract attorney for the ASUO Legal Services, has been located in a former storage closet near the ballroom. Because her office has no heat or air conditioning, she keeps the door open. She’s watched a jazz dancer work for hours to perfect a performance piece, observed dressed-to-the-nines high school students giddy with excitement at participating in a mock UN meeting, and students napping on a bench outside her door. “There’s never a dull moment,” Moro says. “Mostly it’s delightful seeing the whole population of the university pass by me—in protest, in prayer, in pursuit of knowledge, or providing entertainment.” Her office was moved in June to accommodate the renovation, and she wasn’t looking forward to the change.

Another beloved space close to the ballroom is the area now known as the Adell McMillan Art Gallery. The west wall is a bank of 14-foot-high windows, each fronted with a window seat. Students have been seeking out the comfort of those seats for years, says Lobisser. “I’ve been on campus 35 years, and I never go by when there aren’t students sitting in those window seats. That’s their place between classes. It’s kind of special when a building creates such beloved spaces used by generation after generation and helps give students a sense of identity and belonging. I don’t think architects imagined those window seats being so important to the experience of so many students.”

Free speech for all

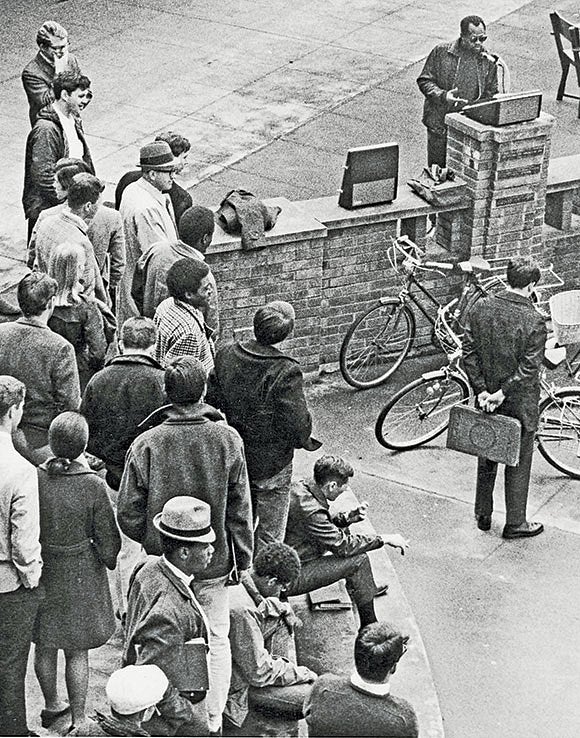

The free speech platform outside the EMU has been one of the most energetic spaces connected with the building. In 1961, a speaker named Homer Tomlinson, who proclaimed himself “King of the World,” was heckled by students while orating from the Fishbowl terrace. According to A Common Ground, a history of the EMU written by former EMU director (and gallery namesake) Adell McMillan, the audience’s intolerance prompted an angry response from UO president Arthur Flemming. The Student Union Board decided to erect a free speech platform on the terrace, with a quote reading, “Every new opinion, at its starting, is precisely in a minority of one.” The wooden platform was later replaced with a permanent brick podium. Few could have imagined the role the platform would play in just a few years’ time, when politics, social change, and student unrest hit the university like a lightning strike.

Political turmoil percolated through the campus in the coming years, and by the time Kip Morgan ’75, ’77 took the ASUO helm in 1969, the campus was in a churn over issues including student autonomy, racism, the draft, and the Vietnam War. The free speech platform “was where people spoke their dreams,” says Morgan, an antiwar and antidraft activist. “All different factions. Religion, politics, and economics were up for debate.”

During those tumultuous years, the EMU was the focus of protest rallies and demonstrations, including a 24-hour sit-in. In January 1969, protesters harassed naval recruiters and burned their recruiting materials. A few months later, students erected shacks on the EMU lawn and invited homeless people to live in them. In a controversial decision that raised hackles around the state, UO acting president Charles Johnson allowed the shacks to remain for two weeks.

Nothing occurred on campus, says Morgan, that wasn’t first discussed at the free speech platform. “It was very open. There was no fear.”

Ron Eachus ’70 became ASUO president in 1970. He says the free speech platform continued to be a nexus of debate, mobilization, and political activity. “It was a place to argue, to pontificate. A place to organize,” he says. “You could stay or walk by, but you couldn’t avoid it.”

Even during volatile exchanges of ideas, students remained vigilant about fairness at the platform, he says. “It was a symbolic place that carried a lot of meaning and was used in a way that reflected that purpose and symbolism. There, you could talk about things you were not able to talk about in class. When you were there, you could talk about the real world.”

The Fishbowl

Despite the spacious charm of the ballroom, and the political intensity of the free speech platform, the EMU space remembered most frequently and fondly is the iconic Fishbowl. Years before it was featured in the 1978 film Animal House, the curved glass Fishbowl had become the center of student interaction on campus.

“That first year, I was over there all the time, hanging out, playing cards between classes,” says Dignan, the 1952–53 ASUO president. “It was new and exciting, a place to go and meet people.” Drummonds recalls that rather than put up with his aggravating roommate, he would park himself in the Fishbowl. “I could block everything out—the noise and the music—and study. I loved the Fishbowl space.” Joe Leahy ’65 remembers spending Friday afternoons during his senior year at the Fishbowl, reading the Register-Guard and sipping coffee. “It was a quiet moment at the end of the week,” he says.

Scott Farleigh ’68, JD ’74, 1967–68 ASUO president, remembers study-break dates at the Fishbowl, and lots of community. “It honestly was my favorite spot,” he says. “It’s where everybody met. I’d go there and meet political allies, campaign people, friends. It was a sort of special place—there was social intercourse for discussion, for open-minded fairness, for meeting people. Ideas were generated there that would never have occurred but for the opportunity presented by the Fishbowl.”

Over the years the Fishbowl has been the site of impromptu revival meetings, Bible study groups, and music performances. It has also provided a sense of belonging in difficult times. In Meet You at the S.U., late UO professor George Wasson recalls that the day President Kennedy was shot in 1963, the campus community gravitated to the Fishbowl. “The EMU was packed. Loaded with people,” he says. The only sounds came from radio broadcasters and the music they played, which included Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings. “Nobody talked. People were crying. The whole Fishbowl—just quiet except for the music and the broadcasts. A stunning moment. I’ll always remember it.”

Renovation plans call for the Fishbowl to retain its original character—including the distinctive bank of windows that inspired its name—even as it receives updates including new floor and ceiling tiles, modernized food service setup and lights, and renovated restrooms.

Chong and other EMU employees are excited about the “new” EMU. She’s excited about the small changes—such as having updated circuit breakers that won’t blow during nighttime study hours and the reinforced south lawn that won’t turn into a muddy bog after heavy use. Kraiman says he never had much affection for the ’70s side of the building, which he felt lacked the structural integrity and class of the original building and its materials. “Every time I see [demolition crews] taking more swings at the building, I go, ‘Yeah!’” he says.

“We knew the 1950s building was worth saving. It had good bones,” says Dan Geiger, EMU renovation manager. “We wanted the new addition to have much more of a feeling that it was modern but it spoke well with the design of the 1950s building. We wanted [the new EMU] to have a sense of timelessness. We didn’t want it to feel dated to a particular time period.”

As a member of the EMU board, Miles Sisk, the junior who considers the EMU his second home, has for the last two years participated in planning the building’s renovation. He’s psyched about the changes—replacing the ’70s building with a more energy-efficient structure, technology upgrades, and new food venues, and the large screens that will hang in the lobby to show student-produced videos. But what really excites him is the effect the remodel will have on students.

“The renovation itself is a catalyst for what goes on in the building. It will give students more opportunities to get engaged with the campus,” he says. “That’s what the renovation is about—not having fancier things, but bringing students back to the center of campus, to a place where they feel more comfortable getting involved, and more willing to do so.”

—By Alice Tallmadge

Alice Tallmadge, MA ’87, is a local freelance writer. Her lingering memory of the EMU is eating taco salads while reading the Daily Emerald in the Fishbowl.