Journalism, by definition, is informed by experience. Reporters document events, interpret meaning, and provide context. They are dutybound to help us make sense of the unfamiliar, and tasked with challenging us to question what we might otherwise take for granted. Yet presently, the journalism profession itself has entered uncharted territory. Technological advances continue to disrupt traditional business models and enable anyone with a smartphone and Internet access to produce and distribute media.

Beyond the core principles of ethics, fairness, and verification of facts, few things in journalism remain certain and nearly everything seems up for grabs. Those of us who are charged with training tomorrow’s journalists are also their partners in inventing what journalism will be. Our classrooms are becoming laboratories, and our most rewarding experiments unfold in the field.

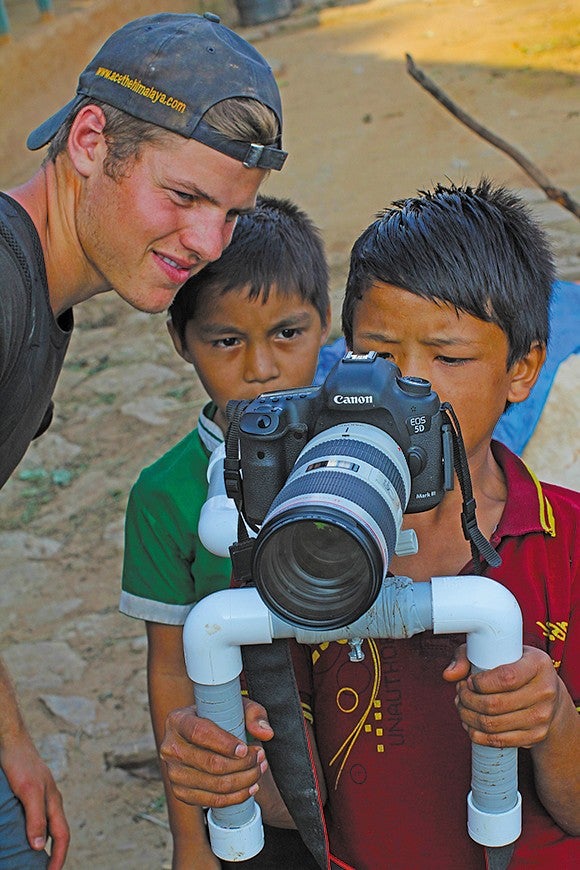

So rather than asking them to conceptualize life inside a communist country, the University of Oregon’s School of Journalism and Communication (SOJC) took students to Cuba just as the United States was renewing diplomatic relations. Instead of speculating about the effects of climate change, students in our Science + Memory program document it each summer in Cordova, Alaska. Our students traveled to rural areas of Nepal following that country’s recent devastating earthquake to report firsthand on relief efforts. In lieu of settling for prevailing stereotypes about people and potential in developing nations, our students build relationships by working alongside them each summer in Ghana, West Africa—as they will during an upcoming trip to Sri Lanka.

Students will tell you: these trips are nothing like vacations. They are rigorous journeys, requiring long hours and challenging work. Participants must prepare for the unpredictable and anticipate inevitable change. Capturing sunrise necessitates gathering gear and scouting to find the best vantage point at least an hour before dawn. Learning to “get the shot” demands patience, practice, and lots of fresh batteries. Student journalists learn to write in any setting and endure many distractions.

Closer to home, undergraduate teams traverse the state each spring to produce OR Magazine, which was acknowledged by Adobe in 2011 as the first student-produced iPad magazine using the company’s digital publishing tools. Through OR Media, students develop strategy and content for Travel Oregon, our state’s tourism commission. Other students explore the region producing “NW Stories,” our experimental documentary series on intriguing people of the Northwest that airs on Oregon Public Broadcasting. What follows are field notes and photographs from some of our most memorable projects in Cuba and Ghana.

Forbidden Cuba

Until a year ago, Cuba was a whispered word among Americans who desired to go but feared facing $250,000 in fines and 10 years in prison (just two possible penalties imposed by the US government), not to mention uncertainties about safety once they arrived. A small provision in the law allowed for education-based cultural exchanges. By this mechanism, two years ago my colleagues and I commenced plans to take 20 journalism students to an otherwise forbidden land. What we didn’t know was that, simultaneously, President Obama, the Pope, and the Castro brothers were secretly working to ease a half-century of strained relations between our two countries—nor that they would resolve their differences so close to our visit.

Our students and faculty members rendezvoused in Miami and departed on a prop plane bound for Havana early Saturday morning on March 21, 2015—just four days after the first scheduled flight was allowed from New York since 1961. We were moved by the realization we would be witnessing Cuba as few would ever see it again: emerging from a veil of isolation and ready to share its wonders with the world.

The rich aroma of Cuban cuisine and the sight of 1950s-era classic cars made us acutely aware we were far from home. Yet much was familiar: bakers browning loaves of bread at the crack of dawn; moms shuttling kids off to school; people everywhere, at every hour, relishing Cuban coffee. “I wasn’t expecting good things,” says Jake Charlson, BS ’15. “I wasn’t expecting anything like what wefound . . . a lot of really happy, amazing people who are extremely proud.”

One stark difference was Cubans’ inattention to screens. For most, the trappings of technology are neither accessible nor affordable. Smartphones are luxury items, and American entertainment is considered contraband. Life is simple, but far from ideal. Most Cubans rely on meager wages and are just getting by. Lines for basic services are long, and many of the comforts we take for granted are out of reach. Yet, there is joy among children, families, and close-knit communities.

Our 10-day journey’s theme focused on universal expressions of art and music. In three-person teams, our students set out to profile six Cuban artists and creatives, including a restaurant entrepreneur, a dancer, a sculptor, a musician, a filmmaker, and an improv actor. “Our goal was to show a deeper human aspect to a country we’ve only known about politically in the news,” says Melanie Burke, BA ’15.

While we were bound by the Cuban government to follow an agreed-upon itinerary, we never encountered the Orwellian surveillance we anticipated. Cuban people were generally friendly, hospitable, and candid in expressing their views.

Carlos Borbon, one of our interview subjects, performs improv—but rarely for laughs. His Spontaneous Theater troupe engages audiences through psychodrama, a form of participatory performance therapy. Their work provides him with a way to express the struggles he encounters in his own life.

Borbon spoke candidly about being harassed by Cuban police because he is openly gay and HIV-positive. Without just cause, he was arrested and jailed two nights before our interview. Before the cameras started rolling, we asked if he feared possible persecution for sharing his story on camera with American journalists. “Consciously, no, but unconsciously, a little bit, of course,” Borbon said. “I don’t think the future is ever going to be easy. But I do believe we have to keep up the struggle, and maybe that is why I am not afraid to do it.”

Borbon’s words were a stark reminder of the courage and sacrifices often required for significant social change. His story is presented with five other artist profiles on the student-created website CubaCreatives.com.

West African Roots

Historians estimate that Spaniards transported more than 600,000 African slaves to Cuba over a period of three centuries. Many of their descendants now practice Santeria, a religion that blends African and Roman Catholic rituals. While in Cuba we visited Cayo Hueso, a neighborhood in central Havana where priests and priestesses welcomed us into their candlelit homes filled with ceramic statues, sacred drums, colorful beads, and other artifacts.

Many Afro-Cubans trace their ancestry to Ghana, West Africa, which was a central hub of the transatlantic slave trade. Formerly known as the Gold Coast, Ghana was the first African nation to declare independence from British colonial rule in 1957. Since severing its ties to the UK, the country has emerged as a peaceful and relatively stable democracy.

Each summer since 2004, the SOJC has taken approximately 20 students to Accra, Ghana’s bustling capitol, to intern at newspapers, radio and television stations, ad agencies, public relations firms, and nongovernmental organizations. Established by Professor Leslie Steeves, the annual six-week Media in Ghana program intentionally places students in positions where they are the only non-Ghanaians. The intent is to provide them with an unfamiliar, immersive, cross-cultural experience. Much like on MTV’s Real World, students live together in one large house. However, after a brief acclimation period they are required to use public transportation to travel to and from their internships. Taxis are plentiful but expensive, so most students rely on trotros, which are privately owned minibuses commonly in disrepair.

Traveling to Ghana was especially significant for Juwan Wedderburn, BS ’15, who was a junior when he participated in the program during the summer of 2014. He is a first generation Jamaican American, and traces his family’s lineage back to Africa. “I always wanted to go to Africa, so it gave me personal satisfaction to get more in touch with my roots,” Wedderburn says.

Julianne Parker, BA ’14, says that the trip provided an opportunity for personal growth, and not just an impressive résumé line. “We can say all we want that we’re here for the internships and for the professional experience, which we are,” Parker says. “But I think no one would sign up for a trip to Ghana if they weren’t looking for something more, whether we know what that is—we may not. But I think we’re all searching for more than just professional experience.”

Weekends provided opportunities for group excursions outside the city limits to explore the country’s tropical diversity and rich culture. However, little prepares students for the experience of retracing the footsteps of slaves at two of the many remaining castles along Ghana’s coast. Our affable African guide led us through dark, dank cobblestone dungeons that are now shadowed by shame. Students who visit share a wide range of insights and emotions.

Carson York, BS ’11, MS ’13, was deeply moved by his experience. “You can’t go through it, not just as a person of European descent, without feeling sort of overcome by guilt,” says the former Ducks offensive lineman, now a manager at Nike. “I feel guilty that someone within my lineage was probably involved in some way. More guilt as a person—that, for whatever reason, humanity was able to perpetrate something so horrendous with so little guilt or moral conflict.”

Sri Lanka and Beyond

We will take a team of students to Sri Lanka during the first two weeks of the December 2016 winter break to document how a country comes together in the aftermath of civil war, tsunami destruction, and current environmental threats to its rain forests. The UO’s Holden Center for Leadership and Community Engagement, known for its service-learning alternative break trips, was our partner for the Cuba experience and will be so again for our journey to Sri Lanka.

These experiences give students unique insights into the human condition and into the universality of diverse cultures, as well as an advantage when entering the job market. “I definitely think my trip to Cuba gave me a competitive edge in my job search,” says Reuben Unrau, BA ’15, who graduated shortly after traveling with us to Cuba. “Going abroad and interacting and interviewing people shows you are open-minded and willing to step out of your comfort zone.” Unrau was recently hired as a production assistant by WBEZ in Chicago, one of National Public Radio’s top stations, on a show appropriately titled Worldview.

This spring, I launched a smartphone-based video production course called Media and Social Change, which is open to students across campus. It teaches participants how to use their pocket devices to capture powerful visual stories with meaningful themes. In fall 2017, our new Social Change in the Digital World Academic Residence Community will welcome its first cohort of students, who will live and take some classes together. The dormitory will be equipped with media production facilities and a screening room, allowing students to get an early start on their media careers.

These developments, taking journalism into a new era, are fitting as the SOJC celebrates its centennial anniversary this year. Albert Einstein once said, “The only source of knowledge is experience.” Theory informs practice, and experience makes it real.

—By Ed Madison

Ed Madison, PhD ’12, is an assistant professor of multimedia journalism in the School of Journalism and Communication.