"My aim as a designer is to create gardens for people looking for a connection to the natural world. This can be as simple as a lovely place to unwind after a week of hard work, or as profound as a cosmological sanctuary for soul searching.

"As winters are cold and wet in Oregon, I started to travel routinely during the months of December through April. A trip to Europe, followed by 15 winters in Asia, and six in South America have had significant influence on my work. My own garden has taken on the form of a Maharaja's harem, essentially an Earthly paradise of opulent sensuous indulgence."

—Jeffrey Bale

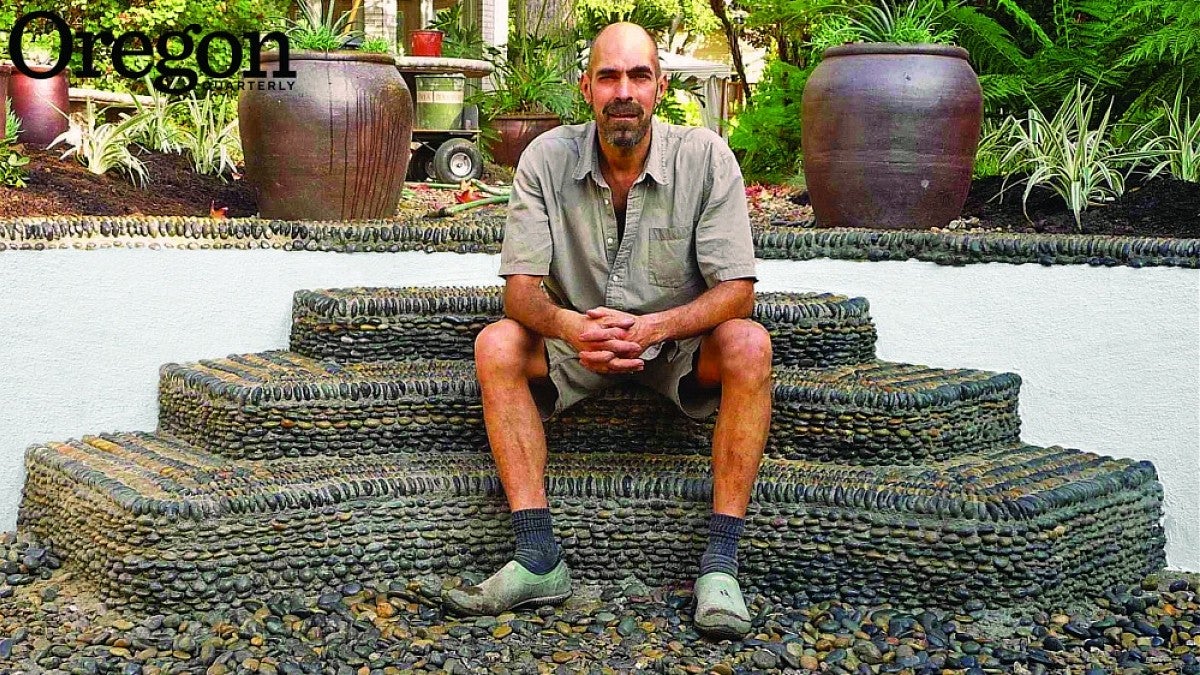

Jeffrey Bale '81 is a nomad. Few people possess passports more frequently or widely stamped: Brazil, Cambodia, India, Greece, Sri Lanka, Morocco—and that's just a short sampling. In his globetrotting, he finds inspiration for the stunning works of outdoor art that are likely to remain cemented in place for many decades.

Bale has trekked around the globe escaping the Northwest winters while seeking out humanity's great achievements in masonry, architecture, and landscaping, from the Alhambra in Spain to the mosaics of Pompeii to 2,500-year-old gardens in Ragusa, Sicily. He sets a world of motifs into his landscape designs, most notably his trademark pebble patios, pathways, walls, and fountains, which reflect natural, spiritual, and astrological imagery.

"I wanted to see the world," says Bale, "and I've been able to travel because I don't have a mortgage." He paid $16,000 for his house in northeast Portland soon after graduating from the university's landscape architecture program, and paid it off when he was just 28. "Smartest thing I ever did."

Bale, who grew up in north Eugene, credits a junior high career-day interview with landscape architect Lloyd Bond '49—who designed the city's downtown Park Blocks—for early inspiration.

"He was a very fine landscape architect, and Eugene is lucky to have the Park Blocks," says Bale, who becomes passionate when talking about well-conceived designs that can endure, inspire, become classic.

Bale values his own instruction from the university's landscape architecture faculty. This was in the pre-AutoCAD era, he says, and had a heavy emphasis on reality-based design.

"The industry is all computers now. It's faster, but less personal, and not very reality-based. My work is more organic," reflects Bale, who rarely even does hand drawings. "I do mockups, I take a lot of pictures. And I'm really into natural materials; they have such soul and resonance."

Bale's stonework, especially, resonates with his connection to the earth and his recognition of a place's soul. Many of the materials he uses are stones he's plucked—he calls it "gentle resource extraction"—from ocean and river beaches, or other treasures he's unearthed near a project's site. You see this local-sourcing ethic in the stones he carted along a two-mile stretch of beach to craft an ornate fire pit inset adorned with the image of a Pacific octopus overlooking Puget Sound; in the four tons of old San Francisco street cobblestones and three tons of beach rock he scored to build a showpiece $100,000 patio and fountain in Sonoma County. "It's a profound thing using material that took millions of years to get to the place where it's at," Bale marvels.

As careful as he is when selecting materials, his technique for using those materials is even more meticulous. Most artists use computers to generate templates, and then—quite comfortably—build mosaics modularly on a work surface in the "dry set" method. This involves placing stones to form part of an image in reverse, pouring grout over the back side and letting it set before flipping it over, anchoring the panel in a concrete slab, and repeating the process to piece together an overall scene. But Bale tediously works on hands and knees, without templates, directly on the mosaic surface. He lays stones in about a one-square-foot patch of fast-setting wet mortar before covering it with plywood, jumping on it to level the surface, and moving to the next square. The process can take days, weeks, or longer.

Bale's unusual technique allows precise control over how deep each stone sits, and he inserts many stones so that the smallest surface areas are exposed. In the long term, he says, this makes it less likely rocks will detach.

Detachment is something Bale often talks about—both in describing a project's potential for deterioration and in terms of how far removed from the natural world many people—even landscape designers—have become.

"We're really disconnected from nature," he laments. "Americans may have a beautiful house, incredible furniture, a great art collection, and a crummy yard. They just come home, go in the house—'mow-and-blow' takes care of things, maybe they barbecue on the patio." Many newer parks and public spaces display the same detachment, Bale says. "Asphalt and white concrete is America, and they're the two ugliest things. It's such a disconnect from aesthetics and from nature."

Bale likes to comment on and challenge thought processes about design through his prolific blogging (www.jeffreygardens.blogspot.com) and photography, as well as in self-published books such as The Gardens of Jeffrey Bale and Gardens of Southern Italy.

He also is developing a proposed book, The Pleasure Garden, based on his ideas about luxurious landscapes where one can revel in the soothing sounds of flowing water and songbirds, inhale deeply the scents of blooming flowers, pluck fresh fruit and eat it on the spot, wonder at beautiful stones, and lie down and nap.

His thoughts and actions work together to create such pleasure—with every garden he imagines, every stone he gathers, every airplane he boards.

"The world's profound," Bale stresses. "If you can even come close to matching that in design, I think you've had some success."

—By Joel Gorthy '98