We may not talk much about it, but most of us know how it feels to be graced by an unexpected kindness. A schoolmate we barely knew shielded us from a bully. A stranger helped us out of a predicament. A partner who could have been angry at our bungling chose to be loving instead.

Kindness has a quiet, private power. It doesn't call attention to itself, and it often appears when people feel least in control of their circumstances. Maybe because of this, kindness as a moral virtue has received short shrift in elevated circles of Western thought. The philosophical greats barely gave it a nod, and literature often framed it as trifling, sentimental, and saccharine—a woman's virtue, some termed it.

Philosopher Caroline Lundquist, MA '06, PhD '13, sees kindness differently. In her view, being kind is a powerful and potentially transformative act. Determined to give the long-overlooked virtue its due, she made it the subject of her doctoral thesis, which traces perceptions of kindness through Aristotelian ethics and Kantian morality all the way to modern culture. "My work is about elevating kindness to show it for what it has always been—of tremendous value and worth," Lundquist says. "The main reason kindness has been dismissed is the same reason we should pay attention to it. It's showing us how vulnerable we are."

Lundquist is an ethicist. Part of her motivation for delving into the concept of kindness was the perennial ethical challenge of addressing the inequities that exist in life, from the rough circumstances that affect some lives from birth to the unforeseen events that throw the most well-planned lives into turmoil. This uncontrollable fact of human existence is often called "luck."

American culture elevates the self-made individual, Lundquist says, but the truth is "sometimes the deck is stacked against you." Misfortune happens. People are born with disabilities, or into lives of dysfunction or extreme poverty. Accidents and illness take away loved ones.

Kindness can blunt the edges of misfortune or luck gone bad, she contends. But the act of kindness goes even deeper. By acknowledging that we all have the potential to be victims of turns in luck, and that we all have the power to ease others' misfortune, kindness links us together. "Kindness is the enactment of a fundamental truth of human existence, which is simply that we are each other's best and worst luck," Lundquist writes in her thesis, "Impossible and Necessary: The Problem of Luck and the Promise of Kindness."

Lundquist, 34 and the mother of two, says her interest in kindness began at a young age. "The only time I got in trouble at school was when I was trying to stop a bully from picking on someone," she says. But her motivation to explore the topic as an academic came from an experience where she feels she failed to extend kindness. A cousin had been tormented at school and was treated harshly at home. Although she and her cousin were close when they were kids, they later grew apart. Seeing him in his early 20s, she noticed he seemed sad, "a shell of the person I knew growing up." She had a nagging feeling she should do something, but she had a new baby at home and was immersed in the demands of her master's program. The day she received her degree, she learned her cousin had taken his life. "I was filled with remorse," she says. "For a year I didn't sleep through the night. Thoughts tormented me—what I could have said or done. And whether it would have made a difference."

Lundquist began to change, becoming more alert to situations where she could express kindness. "I decided it was more important to do too much than too little," she says, "that it is OK to look foolish for helping someone who may be in need."

In her dissertation, Lundquist examines the subject of kindness not only through the eyes of ancient philosophers and ethicists, but also as it is seen in literature and popular culture, citing examples of authors and individuals who have explored or demonstrated its power. These include the loving and gentle Monseigneur Bienvenu in Victor Hugo's Les Miserables; Scout Finch's awakening to kindness toward Boo Radley in To Kill a Mockingbird; South African political martyr Steve Biko's work in the Black Consciousness Movement; and comedian Phyllis Diller's reputation for unflagging kindness. "Caroline makes the strongest case for [kindness] that I've ever seen," says Mark Johnson, UO Philip H. Knight Professor of Liberal Arts and Sciences, who directed Lundquist's thesis. "She blends these real-life examples with examples from novels to give a concrete sense of what this virtue is," he says. "It is not a theoretical treatise."

Sometimes when people think of kindness, Johnson says, they think it involves being a sucker. Or that people will never learn discipline if others are kind to them. But Lundquist's work "shows how kindness means that what you're doing for the other person is directed toward their moral growth and flourishing," he says.

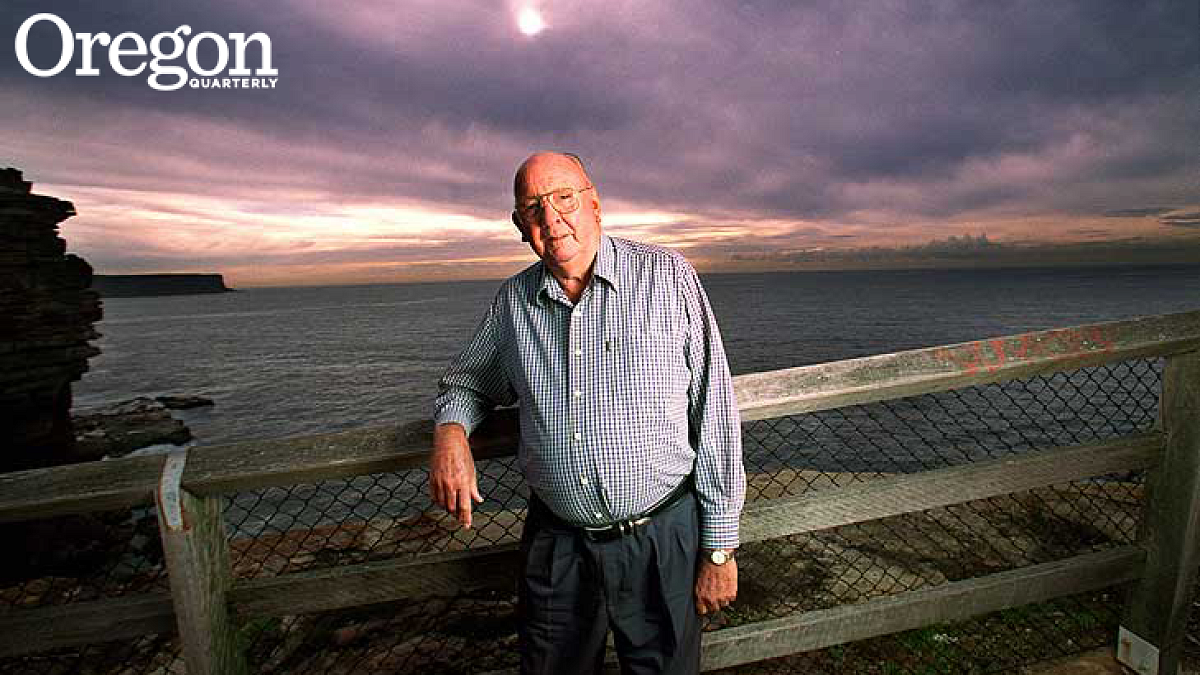

Lundquist has become fascinated with people who live in the vicinity of notorious suicide spots and who choose to interact with individuals who have decided to end their lives. The late Don Ritchie, known in Australia as the "Angel of The Gap," lived near a sheer cliff overlooking the harbor in Sydney. Over the course of five decades, he stopped, by official count, at least 160 people from jumping. At first he actively tried to change people's minds, Lundquist says, occasionally even pulling them from the edge of the cliff. But over time, he changed his approach, inviting potential jumpers to have tea with him on his porch. He listened to what they had to say. When they were done with tea, he let them go. Many went back home. Some continued toward the cliff.

For Lundquist, Ritchie's approach personified true kindness, which means accepting people for who they are at that moment, even if it means knowing they will jump to their death. Some people thanked him after sharing a cup of tea (and before heading to the cliff), she says, saying he had made their last moments meaningful. "He made the difference between them leaving the world in despair and alone, and leaving it feeling someone was there, and cared," she says.

Lundquist is writing a book stemming from her dissertation, and is also considering writing one specifically about suicide interveners. Stories about people not caring are all too frequent, she says, adding, "I'm tired of hearing about that. They don't paint humanity in a positive light. They only tell part of the story."

—By Alice Tallmadge, MA '87