Simple carb. Staff of life. Sacrament, mitzvah, the very body of Christ. Prisoner’s rations. The highest expression of the baker’s art. Irritant, allergen, toxin.

Bread has been baked and consumed, in one form or another, for at least 10,000 years. It requires only four simple ingredients. Yet everything about it—on close examination—is complex, from the interaction of those ingredients in the rising dough to the social and political history bread has been shaped by and has helped to shape. No surprise, then, that when five University of Oregon professors—food lovers all—met last year to kick around ideas for an interdisciplinary life science–humanities honors college colloquium organized around one foodstuff or another, bread quickly emerged as the obvious focus.

The resulting course—Bread 101—challenged both students and instructors. “By the end of the term,” biologist Judith Eisen says, “I realized I knew less than I thought I knew going into this!”

“I had never considered—until I met all these people—the microscopic picture of bread,” says physicist Miriam Deutsch. “When you put everything together in the bowl and mix it up, whoa! The energy landscape of that is so complex.”

But what is bread? Beyond the dictionary definition (to which the Oxford English Dictionary devotes a full page), the answer may depend on whom you ask. Here, each of the course’s instructors reflects on the essence of that most ubiquitous of human foods.

Life Giving Life

Judith Eisen, Neuroscientist

Bread itself is not alive, but it is shaped by living organisms. If we talk exclusively about leavened bread, it requires four ingredients. It has grain, which is typically wheat. It has salt. It has water. And it has some sort of leavening agent. Most of the breads we talked and thought about in class used yeast or sourdough starter, which is yeast plus bacteria. So with the exception of the water and the salt, which is a mineral, bread comes from something that is alive. The yeast and bacteria stay alive until you bake the bread. And the grain that you use, the kernel of wheat, is alive until you grind it. The plant that it comes from is dead—it dies naturally in the fall—and if you grind that grain, you can’t get another plant out of it. But before it is ground, you could take that grain and grow it and get a whole other plant out of it. After it is baked, it helps create life by providing fuel to other organisms. So you can think of it as a sort of cycle.

At age 17, Judith Eisen found a recipe for challah and baked it for her brother’s bar mitzvah. She has been baking bread ever since. “I’m one of those people who likes to be in touch with my food, whatever it is,” Eisen says. At the UO, Eisen researches development of the nervous system in embryos. She also directs the Science Literacy Program. “The world is increasingly technological, and science increasingly encroaches on our life in many ways,” she says; science literacy courses are designed to help students develop “the skills to think about science, to think about the kinds of things that they may hear about in the media and the kinds of things that may impact their lives.”

Energy In, Energy Out

Miriam Deutsch, Physicist

In physics, almost everything you do involves energies: energies being converted, being transformed from one form to another. Bread falls into that equation very, very simply. A slice of bread is roughly 100 calories, so that tells us something about its energy content. Some of it you use because you need to move around, some of it gets stored in your body, and the rest goes out. So in terms of the energy balance, it’s fairly straightforward.

But what also interested me was energy investment: how much energy does it cost to produce that bread? How much energy goes in, how much energy can come out? We know how much can come out, because the food label tells us. But how much goes in? How much energy does it take to bake a loaf of bread, beginning with sowing the seeds? The answer turned out to be very large-scale and incredibly complex. I thought this was going to be straightforward, but when I was preparing the lecture, I thought, I don’t know how to do this—and almost no one knows how to do this! I found only one study, a cost analysis done in Sweden, comparing commercial bakeries with regional bakeries versus home bakers. It really was a humbling experience to understand how much we don’t understand about our global food production: what it really takes to produce food, to keep us going as a society.

Miriam Deutsch has baked her own bread for years—first as a way to recapture the taste and texture of the crusty white bread of her childhood in Israel, then to keep her own kids occupied (“Kneading dough is a very good activity for kids on a weekend”), and these days as a way to decompress from her work, which centers on studying the interaction of light with nanoscale metal particles and potential applications in sensor technology. “I love the contrast. You have this very high-tech professional side to your life, and then you go home and you make bread: there’s something about it that’s very grounding.”

The Thing About Gluten

Eleanor Vandegrift, STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) Educator

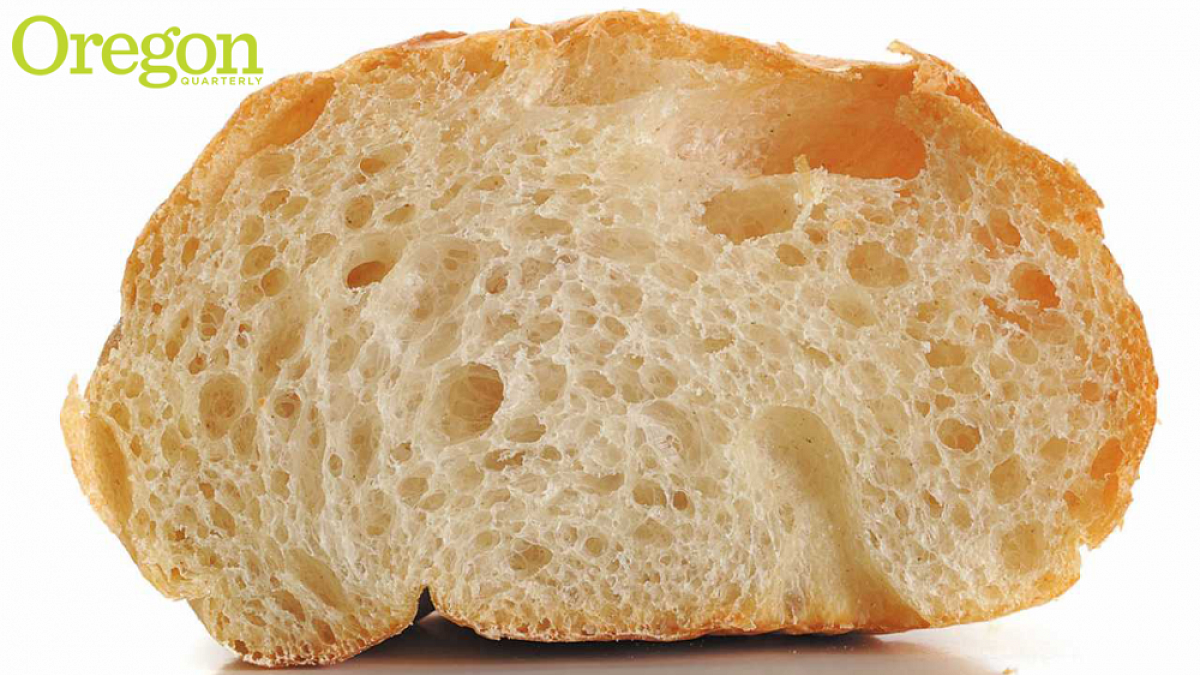

Bread has to have gluten, which comes from classes of two proteins, gliadins and glutenins, that are in wheat and other grains. When they are mixed with water, they bind together. One of them causes the stretchiness in bread, and one causes the recoil. Since teaching the course, my definition of bread has changed to include something that has those properties of stretch, recoil, and bubbling that it gets from gluten.

Commercial bakeries are quite frequently using pure, white flour, where all of the bran and wheat germ have been taken out. As a result, the flour has lower protein content than would otherwise be the case. What industrial bakeries do is add vital wheat gluten. There is so much concern about gluten today, and so many gluten-free foods. In addition to celiac disease [an autoimmune disease in which eating gluten leads to damage in the small intestine], there is a whole range of gluten allergies and sensitivities that have not been studied as deeply. There is some speculation that adding so much extra gluten into our bread is having a society-wide impact on our bodies’ ability to process gluten.

Never mind that some professional bakers won’t slice bread until it has thoroughly cooled to allow the starch to relax—Eleanor Vandegrift still can’t resist tearing into a loaf hot out of the oven, just as she did with the bread her mother baked. She herself dabbles in bread-making: alongside her students, she cultivated a sourdough starter and experimented with baking throughout the term. As associate director of the Science Literacy Program, her primary interest in the course was in crafting and gauging the success of its “backward design.” The instructors started with the learning goals and then crafted curriculum and developed teaching methodologies to help students meet those goals. The faculty members engaged students in learning the science behind bread and its relevance to their everyday lives through discussions, guest speakers, field trips to Noisette Bakery and Camas Country Mill, and a lot of bread-baking.

A Hallmark of Civilization

Jennifer Burns Bright, Literature Scholar and Food Writer

You’ve heard it said that bread is the staff of life? As a humanist, I seek to investigate that in different ways. I’m interested in interrogating what it means for bread to be the basis of life; what is it about bread that is so fundamentally associated with sustenance? You mash up grain and then transform it with water and heat and leavening to create this thing that we associate so deeply with human life. It raises all kinds of questions about what it means to cook and what it means to eat. Does it mean that, because we bake bread, we are civilized? Is that what we mean by life? We have an oven, we have a grinder, we have technology, so we’re able to make a loaf of bread. Or is it important because it’s community-based, because we dine together and “break bread”? And then there’s bread as transformed life, as we see in symbols like Jewish matzoh or the body of Christ. Bread is actually as far from basic as it could be!

In addition to teaching in the comparative literature and English departments, Jennifer Burns Bright writes about food for Via magazine and Eugene Magazine, among others. She is also among those working to establish the UO’s interdisciplinary Food Studies Program, exploring the ways in which food mediates social, political, environmental, cultural, and economic processes. Segueing from sexuality to food isn’t much of a leap, Bright insists: they’re simply “two different ways of expressing desire.” In the class, she focused on literature and journalism that showed how cultural perceptions of bread evolve over time. She grew up eating the sourdough rye bread her Polish grandmother brought home from her job at a bakery outside Detroit; it’s still Bright’s favorite bread. But she has trouble getting a good rise out of her own sourdough; she jokes that all the pickling she does in her home kitchen throws off the balance of yeast and lactic acid bacteria essential to crafting a successful artisan loaf.

Always an Experiment

Karen Guillemin, Microbiologist

The essence of being a successful bread baker is being a successful microbiologist. It matters what kinds of grains you use, and the quality of the water, but ultimately it centers on managing microbial growth. Humans have been microbiologists throughout the history of human culture. We live with microbes all the time. Whether we’re talking about alcoholic beverages or chocolate or cheese or sauerkraut or kim chee or bread, our culture around food has been to culture microbes. It’s only recently, since the advent of microscopes in the 1700s, that we discovered the existence of microbes, but people have long cultivated them in all sorts of food productions, and bread is an amazing example of that. People have known that you’ve got to do certain things to make dough grow: you have to treat it nicely and keep it warm. That’s all microbiology.

One way in which this course overlapped my research was codified in an idea called the disappearing microbiota hypothesis. Western countries have seen the emergence of certain autoimmune diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease—occurrences that are so recent, they cannot be attributed to changes in genetics but, rather, to something in our lifestyle. An important contributor could be changes in our associated microbes and possibly the extinction of ancient microbes. The extensive use of antibiotics may play a role, but another cause—one that this class solidified for me—is that people are much more disconnected from their own food production. In more traditional food production, you would cultivate in your kitchen microbes that you’ve selected because they’re good at breaking down some kind of food product, so when you’re baking bread, you’re cultivating microbes to ferment grains. My feeling is that when you’re cultivating that many microbes, you’re also going to be inoculating yourself with beneficial microbes that are selected to help break down the food that you’re going to eat.

“I’m an enthusiastic cook, and baking is a part of that,” says Karen Guillemin. At home she blogs about local, seasonal cooking in support of the small farmer’s market she helped launch in her Fairmount neighborhood. At work she investigates the impact of beneficial microbes in the human gut. “What was really fun about the class for me is that we could use sourdough bread-baking as a microbiology lab experiment. Normally you’d have to outfit students who are going to cultivate microbes in a lab with safety goggles and gloves. Here we had students go home and mix flour and water together in their own kitchen and watch the dynamics of the growth of a starter.

“Food is such an accessible way for nonscientists to think about scientific questions,” Guillemin continues. Bread—with the complex genetics of its primary ingredient, with the dynamic transformation it makes from simple paste to exquisite slice, with a history inextricable from humans’ own history—revealed itself as an elegant entrée to the scientific method. “We realized we could do everything we wanted to do just focusing on one product.”

—By Bonnie Henderson

Bonnie Henderson, BA ’79, MA ’85, is the author of, most recently, The Next Tsunami: Living on a Restless Coast.

Rising to the Top

Some of the Bread 101 instructors’ favorite breads are products of their own or family members’ kitchens, but here they share a few of their favorite commercial loaves produced by small bakeries on the West Coast.

Portland

German Bakery: Seedless sourdough rye bread

Salem

Cascade Baking Company: Ciabatta

Eugene

Noisette: Baguette, spent grains bread, olive bread

Eugene City Bakery: Olive bread, pane antico

Hideaway Bakery: Old world rye bread

San Diego

Bread and Cie: Olive bread