Back in the funky ’70s—when shag carpets, waterbeds, and beaded curtains were all the rage—Robb Bokich ’75, MS ’79, needed inexpensive furniture to fit his lanky six-foot-three-inch frame. On a borrowed machine, he taught himself to sew, and after a marathon trial-and-error session, he completed his first fluffy furniture: pillows large enough to lounge on. Soon, friends were paying him to stitch and stuff pillows for their homes. Demand for the pillow furniture grew, so he built a booth and started selling his bright patchwork “hippie furniture” at the Eugene Saturday Market in 1973. Thirty-eight years later—“Who would’ve believed it?” says Bokich—his pillows are comforting customers in twenty-six countries around the globe.

Sink into a foam chair or loveseat at Robb’s Pillow Furniture (on River Road in Eugene) and you’ll feel the reason for his success: Wrapped in velvety fabric and cushy soft—yet dense enough to cradle your back and shoulders like a cozy embrace—the padding conforms to your body and your movements like silent, shifting sand. Tuck a small pillow behind your neck and place another across your lap for a wrist-rest, and you’re set for hours of comfortable reading, writing, video-viewing,

or laptop work. The secret to his furniture’s supportive loft? “It’s all in the cut of the foam,” Bokich explains.

What began as Bokich’s creative effort to pay college expenses became a career that propelled him far beyond any boundaries he and his family may have imagined. During high school, a horrific car accident had left him with hemiplegia, a nearly total paralysis of the left side of his body caused by brain damage. He credits his parents with making him responsible for his own life and insisting he become independent. “I had a big clunky leg brace and I used a cane, but I limped a mile and a half to school every day,” he says. “I had no mouth control, only garbled speech, and I drooled. Really, I was not a very attractive individual.” With the small insurance settlement from the accident he did what most teen boys would do (bought a car) and what few severely disabled people might have dared: after graduation, he took a twelve-month trip around the world. Alone.

The brain injury, says Bokich, left him with a child-like level of derring-do that served him well during his travels. Landing in the Philippines, he was forced to speak English slowly and clearly so native people could understand him—perhaps the best speech therapy he might have undertaken. He hopped a freighter for southern ports, then navigated his way to Japan to attend the World’s Fair. While in Japan, he broke his leg brace and wrestled with language and financial barriers to have another one made to his specifications. Throughout the trip, he financed side excursions with wise decisions about currency exchange rates, garnering business and math skills that would prove valuable in his future endeavors. By the time he returned to the United States a year later, he felt physically and socially prepared for the challenges of college. After completing two years at Idaho State, he transferred to Oregon in 1973 and started sewing just a few weeks after arriving in Eugene.

Pulling down As and Bs in his full-time UO classes, Bokich juggled homework and business quandaries. With sales of his pillow furniture consistently rising (he’d added a booth at the Oregon Country Fair), he needed an inexpensive source of shredded foam, mountains of it, and to keep costs low he decided to shred the foam himself. He discovered an interesting machine under a tarp in a friend’s barn: a century-old wool carder. Bokich bargained the owner down to $75—half of the original asking price—and began the laborious task of customizing the machine for his use. For more than a year, he tinkered with the contraption between classes and homework, meanwhile stitching and stuffing pillows till the wee hours of the morning. He finally designed a set of bladed teeth that would cut and shape the foam the way he wanted it, providing the air-filled “zero pressure point” loft that he patented in 1984.

After earning his master’s at the University, the pillow business was doing so well that Bokich just kept sewing. Local buyers and UO students from far-flung locations form the largest part of his customer base (Robb’s pillows have been shipped to Afghanistan, Malaysia, Indonesia, Japan, and even Iran). But perhaps the most fulfilling use of his pillow furniture came about as a surprise to Bokich. One of his regular customers—an occupational therapist from the Eugene School District—found that the furniture’s body-hugging qualities were especially comforting to her special-needs students. Her testimonial states that Bokich’s basic four-foot-square pillow chair “nearly surrounds a student who sits in it, providing the deep pressure that helps calm the nervous system.” Another special-needs customer says the furniture “somehow finds my most effective center of gravity, allowing me to feign a ladylike stillness as it envelopes and supports me. A must, especially if you happen to be autistic!” In honor of these special customers, Bokich renamed his four-foot-square raindrop chair: It’s now called the “hug” chair, and is still priced at $79 to maintain affordability. Bokich regularly attends national conferences, where he promotes and sells his pillow furniture to therapists and health practitioners.

With only the help of his family (wife Emily Wille and her son Jeff), Bokich’s pillow furniture is still stitched, stuffed, and shipped from his original shop on River Road to customers around the world. A vacuum-packing process condenses the hug chair to a box the size of a carry-on suitcase. Bokich encourages customers to ship his hug chairs to their kids or grandchildren, and watch them as they open the small package and a huge pillow pops out. “The look on their faces—now that’s priceless!” he says.

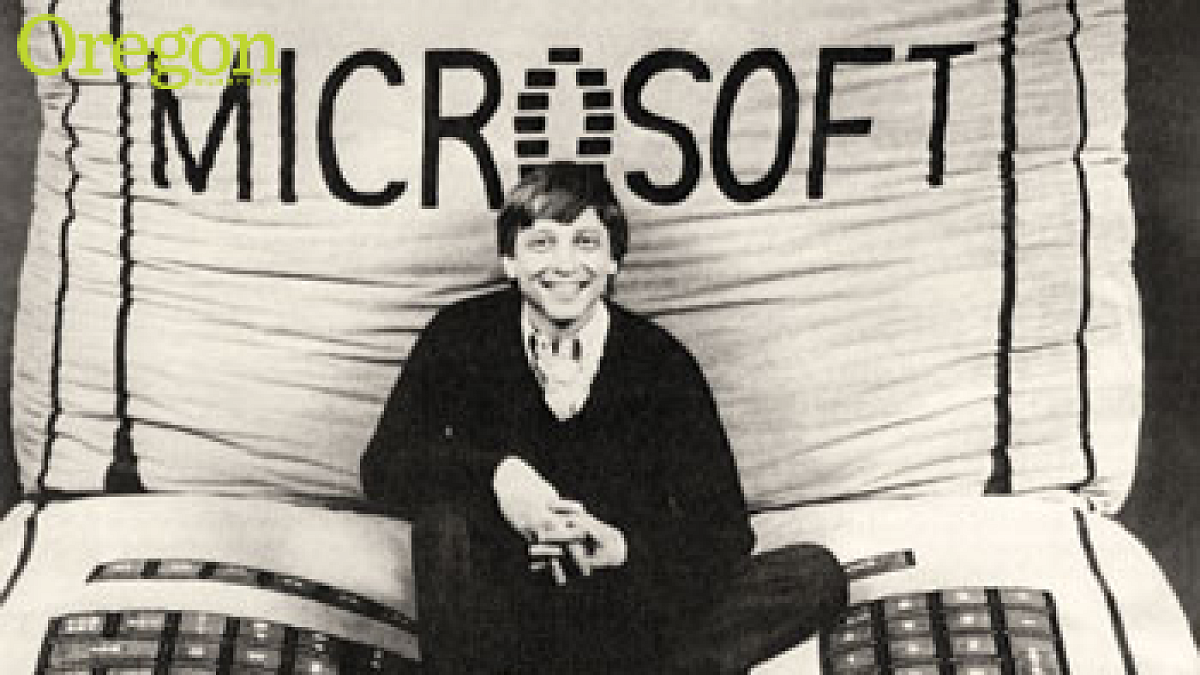

Boyish Billionaire In the mid-eighties, Robb Bokich got a call from People magazine, wondering if he could sew a custom order for a photo shoot they were planning. "They found me through word of mouth, or the phone book, I guess," he says. "They wanted to do a play on words, a huge, soft pillow model of a computer for this company called Microsoft." Bokich stitched up a couple of mattress-sized pillows and enlisted an artist friend to paint on the logo and a complete computer keyboard. Then he delivered the pillows to Seattle so a twenty-eight-year-old Bill Gates could lounge on them for the shoot. "I suppose you'd call that a soft landing," quips Bokich.

—By Katherine Gries ’05, MA ’09