"Among the strangest, and yet most interesting, personalities to attend the University of Oregon was Opal Whiteley '21, now a patient in a public mental institution in England." So began a June 1949 Old Oregon story on this enigmatic Oregonian, whose mysterious life and work continue to defy consensus.

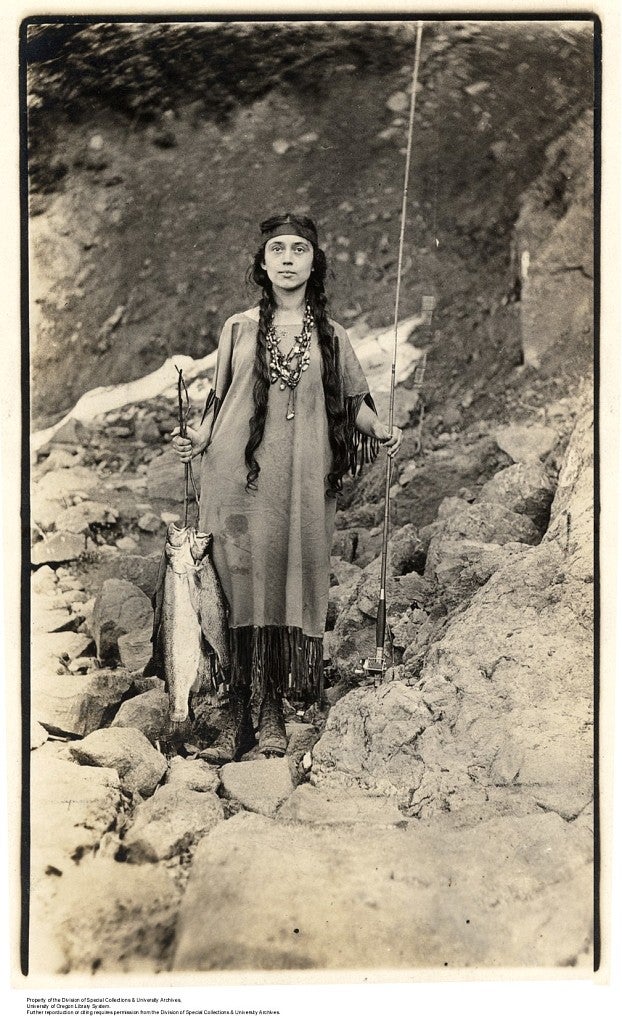

Just inside the door of the Cottage Grove Public Library stands a life-size bronze statue of a young girl dancing joyously, her bare feet surrounded by tall grass and an inscription that reads, in part, "The winds did sing. The leaves did sing. The grasses talked in whispers all along the way." It is a lovely piece, a fitting monument to childhood itself, as well as to the enigmatic author of those words, who spent most of her own childhood living near the town.

The text comes from The Story of Opal: The Journal of an Understanding Heart, a book published in 1920 by the Atlantic Monthly Press of Boston, Massachusetts. Its author, the girl depicted in the statue, was most commonly known as Opal Whiteley. Those two facts are about all everyone seems to agree on in what became a literary controversy that continues to this day.

* * *

On September 24, 1919, 21-year-old Opal Whiteley of Oregon travelled to the Boston office of Ellery Sedgewick, editor and publisher of the Atlantic Monthly. The Atlantic had recently started publishing books, and Whiteley brought a copy of The Fairyland Around Us, a volume she had self-published the previous year, in the hope of selling it to the Atlantic Monthly Press. Sedgewick wisely declined to publish the uneven hodgepodge of a book, but asked about a childhood diary Whiteley had mentioned in her cover letter requesting an appointment. She told him she still had the diary, but that it had been torn to pieces by a younger sister. The diary fragments were sent for, and the young author spent the next several months supported by Sedgewick while she worked on producing a manuscript from the reassembled pieces. The diary appeared during 1920 in installments in the Atlantic, and was published later that year by the Atlantic Monthly Press as The Story of Opal. Early on, readers were largely accepting of the work, but as the chapters unfolded, some began to express doubts as to the diary's authenticity—a point that is still argued over today.

Opal Irene Whiteley was what her parents named her. She was also known at various times as Opal Stanley Whiteley, Françoise d'Orlá, Marie de Bourbon, Francesca Henriette Marguerite d'Orléans, Françoise Marguerite Henriette Marie Alice Léopodine d'Orléans, and Françoise Marie de Bourbon-Orléans. But when people argue about who Opal Whiteley really was, they tend to talk about one or another of three seemingly disparate Opals: Opal the Sunshine Fairy, Opal the Fraud, and Crazy Opal.

The debate usually involves someone emphasizing one of those three aspects of her life and personality and downplaying or denying the others. It is probably impossible to settle for once and forever all the many claims and counterarguments concerning who she was, what she did or didn't do, and, especially, why. What is certain is that she created a memorable character—the little nature girl now immortalized in bronze—one that still appeals to a great many readers.

Whiteley and her book have generated panel discussions, a blog, biographies, and, despite the many scholarly doubts as to the book's authenticity, a grammar school nature studies curriculum that presents the work as that of a seven-year-old child.

* * *

The Whiteley's lived at times in shoeless poverty, but their cultural life was richer than one might expect, given the family's financial instability. Opal's parents were literate and her mother often read stories and poetry to the children, and provided them with music lessons. Her childhood took place in the first decade of the 20th century, in a gritty Oregon that still depended on horses and mules, a landscape and society richly described by James Stevens and H. L. Davis. She was a highly intelligent, imaginative, lively, and precocious child, full of questions and given to daydreaming, much like the Opal of her 1920 book. Her father doted on her, and she must have been a charming little girl.

It is the particulars of that childhood, as portrayed in The Story of Opal, that are endlessly argued over. The specifics of landscape, many of the people, and at least one of the incidents mentioned in the book have been verified by researchers. Other details are simply too fantastic for most people to swallow. Among the more unbelievable aspects is the prevalence of French words and phrases within the book, along with a slathering of heavy-handed clues hinting that little Miss Whiteley was actually the orphaned daughter of French aristocrats.

* * *

From a literary perspective, The Story of Opal reeks of artifice. It is not, as the author claimed, a seven-year-old child's diary, but rather a novel in diary form, beginning with an introductory chapter, ending with a dénouement, and employing stock plots, foreshadowing, chapter finales, and a blatantly disingenuous worldview clearly designed to appeal to adult sensibilities. It belongs to an identifiable genre of 19th-century mawkish stories of childhood, such as Martha Finley's Elsie Dinsmore novels, which feature an oppressively sweet-tempered little girl who is constantly running into parental trouble by being so very earnestly good.

John Steinbeck once pointed out that every novel contains a character who is the author's wished-for self. This imagined self is who we read about in The Story of Opal. It is probable that Opal Whitely really was a sensitive child, attuned to the great beauty of the natural world in imaginative ways that amounted to a sort of primitive and intuitive mysticism. She may well have known trees whom she regarded as friends, and likely had a great fondness for animals and flowers. Whiteley could not have written as she did without being, to a considerable extent, the person she portrayed. Literature does not appear suddenly and fully realized out of nothing, but rather comes from within the author, drawn up in memory buckets from the well of experience. The character she made of herself could not have held such appeal for so many without the readers' recognition of the underlying artistic truths contained within the novel and within themselves.

The appeal of Opal the character (as distinct from Whiteley the author) explains a great deal about why readers today, primarily in Britain and the United States, still feel strongly enough about this book to defend its author on blogs and in panel discussions. Skeptics and true believers alike may yearn for someone like little Opal, with her unsullied outlook and mystical relationship with the natural world and with God. Her defenders, who often call themselves "Opalites," fall in love with the self-portrait of this sweet little girl, and loving her, seek to defend her from her critics. Her critics are often overly dismissive of the book and its author not because of its literary merit, but because it has been promoted as an actual diary. This critical vehemence, in large part, may come from a feeling of betrayal because Opal, as the Sunshine Fairy character, is so seductively innocent and has such a great appeal that one can be fully aware of the deception and still want to believe in such a delightful creation.

* * *

Whiteley's story is also described as a mystery. Mystery is a wonderful word, one that reliably sells books and magazines and has provided gainful employment for generations of publishers, editors, and writers. In the matter of The Story of Opal, the mystery is not really whether or not the author misrepresented her manuscript, but what her state of mind was at the time.

Whiteley had a photographic memory, and drew attention at an early age by reciting long passages from the King James Bible. She took a keen interest in botany and wildlife biology, and from her studies could name hundreds of species of plants, animals, and insects by both their scientific and common names. At the age of 12 she came to the attention of G. Evert Baker, a Portland-area lawyer who was lecturing in Cottage Grove on behalf of Junior Christian Endeavor, a religious social organization for adolescents. He urged the girl to start her own local chapter of the group and recruited her as an organizer. A few years later she was touring the state, charming large crowds and helping to rapidly increase the number of Junior Christian Endeavor chapters. In the process she learned about the value of self-promotion, and she learned to rely on the kindness of the strangers who fed and sheltered her. These two lessons became key survival strategies that served her well throughout her life.

The press attention that year came when, during a week-long visit with an aunt in Eugene, the teenager visited the University of Oregon and caused a stir among the faculty with her extensive knowledge of geology, wildlife biology, and botany. Professor Warren D. Smith, head of the university's geology department at the time, declared, "She may become one of the greatest minds that Oregon has ever produced." Plans were put forth to waive the university's requirement that students complete high school, so that Opal might be given a full scholarship to the university. In the end she had to wait a year while she finished her senior year of high school, and she was admitted in the fall of 1916 with a small, partial scholarship. Her university career lasted two years, during which she managed to complete about a year's worth of studies before dropping out, unable to come up with the funds needed to pay tuition.

* * *

She was clearly ambitious—prior to her visit to Ellery Sedgewick at the Atlantic, she spent a year in Hollywood, trying to break into the movie business. She was also clearly suffering from mental health troubles. She was said to have been plagued by nightmares and to have complained of being followed by shadowy figures; between 1916 and 1922 she had four recorded episodes of what were called "nervous breakdowns." Each of these lasted several months and each came following months-long periods of extremely intense work—long days and overnight sessions running on little more than nervous energy.

Somewhere along the line she developed an idée fixe, believing that she was actually the orphaned daughter of Henri d'Orléans, a French nobleman and 19th-century explorer and naturalist who died in 1901. She must have needed that story very badly. Perhaps it helped her to understand herself and her place in the world. William Kittredge once wrote that much of what we struggle with as humans is the development of an evolving story about ourselves that allows us to make sense of our lives. Some of these narratives are healthy stories that help us to survive; others are unhealthy. All of these stories are necessary responses to life's experiences.

Whiteley was acknowledged as exceptional while still a preteen—exceptionally intelligent, exceptionally knowledgeable, and an exceptionally charismatic public speaker. At least adults saw her that way, although she seems to have been something of an outcast among her schoolmates. It sometimes seems a wonder that anyone survives adolescence, with its hormonal rollercoaster rides and doubt-filled search for a sense of self in a time of such substantial physical, emotional, and social changes. An exceptionally talented and socially awkward girl, likely experiencing the effects of bipolar disorder, might understandably develop an exceptional explanation for why she found her life as it was.

Through her nature studies, Whiteley was familiar with the now long-discredited 19th-century genetic theories underlying both Eugenics and Social Darwinism. A century ago, many mainstream scientists, as well as notables such as Oliver Wendell Holmes and Andrew Carnegie, believed that moral inclinations, character traits, and intelligence were unavoidably inherited, just like one's hair color. If Whiteley felt superior to those around her (and she was told repeatedly that she was) and wondered at the reason for that, then being the orphaned daughter of European aristocrats, rather than that of a poor Oregon logger, would have offered an attractive explanation. Later on, it might also have explained her nightmares (the result of childhood kidnapping trauma) and those unsettling feelings of being followed by unseen strangers (agents hired—sometimes for her good and sometimes with ill intent—to keep an eye on the orphaned princess.)

It seems to have taken Whiteley a few years to fully develop the story of her ancestry. During her time as a student at the University of Oregon, she told a local woman that she was an orphan. A few years later, in Los Angeles, she was saying that she had been born in Italy. By 1918, when she arrived in Boston, her story had become that of a French orphan.

It would be difficult to say to what degree Whiteley believed in her increasingly elaborate story of marriage at the age of four to the Prince of Wales; shipwreck; kidnapping; being carried from Rome, Italy, to Portland, Oregon; and being placed in the care of Ed and Lizzie Whiteley. Her frequent and almost casual fabrications concerning her past show that she was no stranger to deception, but the fact that she stuck to the story for the rest of her life seems to indicate that she actually believed it. It's not hard to see how such an intensely imaginative person, playing a role long enough, could virtually become the character she started out portraying.

* * *

Opal Whiteley never returned to Oregon or to the United States. She spent time in India, then settled down in London in the early 1930s and lived a marginal existence supported by wealthy patrons, a scattered few freelance writing assignments, and babysitting. Her neighbors saw her as a local eccentric, a bit daft, perhaps, but harmless. Whiteley was institutionalized in 1948 after her neighbors complained to the authorities that she'd been shouting in the street and was living in squalid conditions. She was diagnosed as having "paraphrenia with paranoid features." Paraphrenia is usually interpreted nowadays as a late-onset form of schizophrenia that typically appears at about 40 years of age, though at the time it had a broader definition and served as a general term for delusional disorders that begin in middle age. The June 1949 issue of Old Oregon (now Oregon Quarterly) included a touching appeal to readers to contribute to the Opal Whiteley fund, care of Mr. Ellery Sedgewick at the Atlantic Monthly, to assist with her care.

Whiteley spent the last 44 years of her life in a British mental institution, growing increasingly paranoid. She believed herself imprisoned, and by the early 1970s came to believe that Jews from outer space were masquerading as people she knew and planning to invade Oregon.

* * *

Those who condemn Whiteley often see the diary as a coldly fraudulent hoax. Some of her defenders insist that no fraud at all occurred, while others conclude that the fraudulence was only partial, and those parts excusable on the grounds that the author was mentally unstable. Reconciling the paradoxical aspects of the author's life and art is challenging for many readers. That someone as enticing as the Sunshine Fairy was also a liar and a moocher who hurt her own family deeply by denying her parentage is, understandably, difficult for some readers to accept. But to ignore the harm she brought and focus only on the beauty she created does a disservice to her, to literature, and to history.

It has been 95 years now since the day Opal Irene Whiteley kept her appointment with Ellery Sedgewick. My guess is that she was seeking not just a book deal, but acceptance of herself as well. In the near century since that day, neither those who condemn her for her fraudulence nor those who canonize her as a saint have managed to grant her the unconditional approval she so desperately sought.

—By Robert Leo Heilman

Robert Leo Heilman lives in Myrtle Creek and is the author of Overstory Zero: Real Life in Timber Country. His last piece for Oregon Quarterly was the Autumn 2011 cover story "With a Human Face: When Hoedads Walked the Earth."

The Opal Whiteley Papers, a collection of correspondence, writings, newspaper clippings, photographs, and other ephemera relating to the author, is housed in the University of Oregon Libraries Special Collections and University Archives. The collection also includes a copy of Whiteley's self-published book, The Fairyland Around Us.