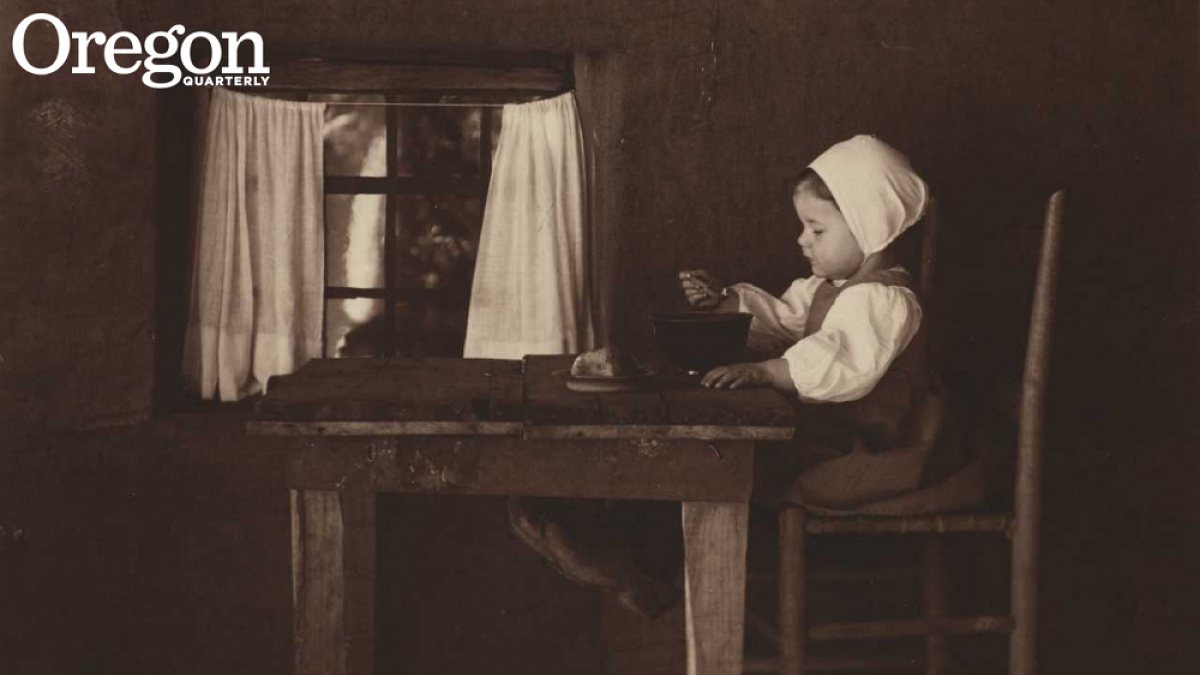

I remember that afternoon ten years ago quite clearly. The month is November, it is a Wednesday as I make my way through the darkening hallways of the Frye Art Museum in Seattle. There is less than an hour to go until closing when I am assaulted, hit over the head, by art. A framed image of a young girl at a simple table holds me in its place. I can’t look away. As in the sight of a new, mysterious lover, I find myself transfixed.

Instinctively, I scribble down a few lines and close my notebook. I go on with my life. But the photograph calls me back. There’s an inexplicable detail in the courage of the child’s spoon against the window’s broad horizon that I need to experience again. Four years after my initial visit, I return to the museum in search of that same piece. With the assistance and agile detective work of the gift shop cashier, I find that I’ve fallen for the photograph “Hunger Is the Best Cook” by Oregon photographer Myra Albert Wiggins.

Much of what I’ve learned concerning Wiggins’s life I gleaned from Carole Glauber’s excellent book, Witch of Kodakery (Washington State University Press, 1997). Through this account, I began to understand the facts of Myra Albert Wiggins’s history.

Wiggins not only created award-winning photographs, she painted, taught voice, wrote a regular column for the Seattle Times, and gave “lantern lectures”—a precursor to PowerPoint presentations—out of her home. In other words, she was intrepid. How can one not admire her spunk? As an early adopter of the camera and the bicycle, she was the YouTube channel host, the “app” inventor of her time. And although Wiggins had the advantages of a wealthy childhood, her economic situation reversed course dramatically when she married childhood sweetheart Fred Wiggins on November 24, 1894, at the First Presbyterian Church in Salem.

Fred Wiggins worked as a clerk at the Holverson and Company Dry Good Store. Surely, Myra’s father, president of the Capital National Bank, must have warned her against marrying the boy. And although Fred eventually graduated from store clerk to owning his own shop to running a plant nursery in Toppenish, his business ventures were largely failures. Ultimately he became a traveling salesman crisscrossing the country by train one hundred and seven times. Myra’s photographs often paid the bills.

* * *

Hunger Is the Best Cook

—after a photograph of Myra Albert Wiggins, 1898

Dark bowl, small mouth, sumptuous spoon —

Whatever there is

there’s not much here,

but the girl’s intent —

enraptured nearly in the pause

and trick of it, the mythic

mirror of abeyance. Her body

opens toward the rim

of awe — all lick and swallow,

imagination readying the tongue.

* * *

Is art simply a hymn to reconfiguration:

Wild huckleberries,

wedge of bread, broken chaff

from the season’s ripe wheat?

The museum patron

presumes the sharp taste —

believes fully in the meal

where the spoon doesn’t waver —

where the girl will

never bring this moment to its end and eat—

* * *

But this is not the story

of the actual:

moon-faced, well-fed,

photographer’s daughter

re-clothed and then

again, for a mother’s ambitious narrative.

The costume, the curtains, the fable

rise in what the woman

called The Vermeer Style —

deficiency reshaped for pleasure’s sake.

* * *

Fistfuls of wildflowers

rupture the room as she shoots

frame after frame

cajoling the unstudied studio pose.

Is her family shrapnel or daisy chain?

Wiggins’ curved hand

charting the shutter: half right, half wrong —

lighting through to

the alchemist’s kitchen —

—By Susan Rich

Today there is no listing for Wiggins at the National Museum of Women, and the Smithsonian’s website mentions only one of her photographs: “Augustus Saint-Gauden’s Class at Art Students League 1892 or 1893.” Now in the twenty-first century, Myra Albert Wiggins is in danger of extinction—like so many artists before her. Why is Myra Albert Wiggins a miniscule footnote in early American photography? And why am I so drawn to her work?

What I do know is that her photograph “Hunger Is the Best Cook” arrested me, spoke to me in ways far beyond the image on the wall—an image that I didn’t understand as a photograph but more as poetry. In a way, I entered the photograph like Jane and Michael Banks enter the chalk drawing on the London pavement and, along with Mary Poppins, canter over soft hills via three painted carousel stallions. The photograph transported me into the room with the child, alone, moving me toward an unknowable taste from a magic spoon.

Somehow I have to confess: I became that child—and at the same time was unexpectedly transported to my own lonely childhood. Through the photograph I was able to transcend time and space; to move in history back to 1898, to a little girl, feet dangling, face intent on her task.

It strikes me that this movement both outside the self and at the same time further into one’s personal history is exactly what poetry accomplishes. And what I’ve now learned, visual art can also do. There’s a fancy word for writing about visual art: ekphrasis. It derives from the Greek and literally means to “speak out.” Yes, I believe pictures do speak although it’s a trick to hear what they truly want to tell us.

For a long time, I was suspicious of ekphrastic work. It seemed for people of another pedigree—those with fountain pens and a fluid knowledge of, say, Greek. To begin writing about Wiggins’s work, I needed to understand my own definition of ekphrasis. What I came up with is this: Ekphrastic poetry is a written response to a visual painting, photograph, dance, sculpture, Ikea catalog, child’s drawing, or bumper sticker. An ekphrastic poem begins with inspiration from another piece of art and with the understanding that art

begets art.

I began my project understanding nothing of late nineteenth-century photography. In fact, that night in the museum, I believed I was looking at a Dutch painting, not a photograph at all. Looking directly at “Hunger Is the Best Cook,” this is what I wrote:

Dark bowl, small mouth, sumptuous spoon—

Whatever there is

There’s not much here

My first ekphrastic attempt was to describe what I could see as well as what I could not. Whatever oatmeal or apple brown betty the girl hopes to eat is suspended in the dark, held in midair. There’s a cinematic quality to this piece—a moment caught out of time that exists in the continuous present. The viewer can never know what comes next in this hungry child’s life. Perhaps this is part of the mystery that elevates art and makes the ordinary so extraordinary.

As I drafted “Hunger Is the Best Cook,” I spent a good deal of time staring at a copy of the photograph in the Frye’s catalog from the show Pioneer Women Photographers. And yet, little of the photograph finds its way into the poem, except for the girl. Most of the poem questions how art does what it does. Viewing this piece on a museum wall, it never occurred to me that the photographer had built the table specifically for this picture, cut black construction paper to divide the window into six panes, or dressed her three-year-old daughter head to toe in a Dutch peasant outfit from another time period.

The more I learned, the more interested I became. Here was a woman staging her photographs—connecting photography to cinema from the very beginning. The piece is a fiction—the room a stage, her daughter far from a hungry peasant. I felt even more intrigued by the piece knowing her lie had appeared so true.

* * *

By the time I began writing “Polishing Brass” a few years later, I’d read of Wiggins’s acceptance in key New York art circles of her day. For a brief moment, from roughly 1903 to 1909, Wiggins claimed a corner of the international spotlight. In 1903, she was honored with a one-woman show at the Chicago Art Institute. In 1904, Alfred Stieglitz included her work in the photographs he sent to The Hague International Photo Exhibition. Her images hung beside the work of Stieglitz, Sarah Ladd, and Edward Steichen representing the best of the photo-secessionists—the early twentieth-century movement that promoted photography as fine art. Sadly, Wiggins’s fame was short-lived. Today, familiarity with her work has all but disappeared.

And so a photograph of her maidservant, Alma Schmidt, polishing a brass pan seemed linked to Wiggins’s own obscurity. Only through Glauber’s account of the photographer’s domestic life does it become clear who the models are for many of Wiggins’s prints. Yet, in more than a dozen works, the same young woman continues to polish brass, spin wool, serve food, and attend a child—all in a Dutch peasant costume. Who was this young woman beyond a servant in the Wiggins’s home? What did she make of her mistress’s art? Their relationship exists somewhere in the photograph, but it seemed I could only imagine it.

“Polishing Brass,” an extended meditation on beauty and its deceptions, was one of the more difficult poems for me to write. How to pay tribute to the unknown model without a poem entirely made of questions? Again, I began with the image in front of me:

rivulet of vertebrae

vestige of one breath-

takingly long

and sexual arm

which grasps

the ledge

Already, I’ve imposed my own point of view on the work. The figure has been transformed into a sexy icon—no longer a mere maidservant. Here is a young woman seen, but not known, more than a hundred years after her picture was taken. Taken into the twenty-first century—but without a history. Has something been pillaged from her dignity, to be remembered only as a maidservant doubling as a model in Dutch hand-me-downs?

The poem pushes to extend beyond the frame of the picture, to connect the afternoon of Wiggins and Alma working on the composition together with the moment the reader experiences the poem, no matter where in the world she may be: Almeria, Soho, Barcelona. I want to transcend the image and find the flesh-and-blood woman who stood before the lens. Who was Alma Schmidt? Whom did she love?

Once again, it is what isn’t here that interests me the most. As poet and essayist Mark Doty observed recently, “You don’t need a poem to show you the work of art . . . that’s how not to write an ekphrastic poem.”

Instead, he said—and I am paraphrasing here—we write ekphrastic poems to focus and examine our own experience from that visual anchor. The image is a container for our own emotional context. It carries our obsessions. A good ekphrastic poem both acknowledges its source and moves away from it.

* * *

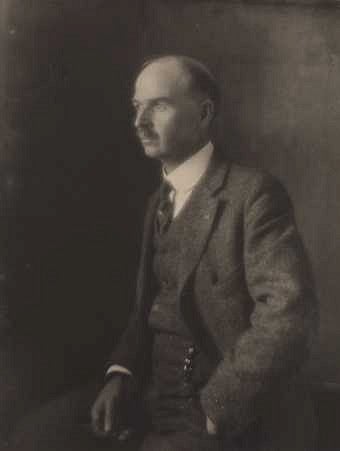

In “Mr. Albert Wiggins Recalls Their Arrangement,” the springboard of the image all but disappears. The persona poem, in the voice of Myra’s husband, Fred, is based instead on a line from Glauber’s text. She states that at an exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum where three of Myra’s pieces were shown, Fred, “bursting with pride,” walked around the show stating he was “just Mr. Myra Wiggins.” In the photographs of Fred Wiggins, he looks every part the serious businessman—handlebar mustache and receding hairline. I feel sorry for Fred. His car dealership went broke, his nursery plants died in a cold snap, and he was still working as a salesman well into his eighties.

Before taking on Fred’s voice, I had never written a poem from a man’s point of view. And yet, I became convinced that I understood Fred Wiggins intimately. Or did I? Maybe his jovial nature and overt praise of his wife reminded me subconsciously of another man I had known. Only in reflection could I see why Fred was so familiar to me.

There were long separations when either Fred or Myra traveled for work. Glauber portrays a strong and loving marriage—but no one could possibly know how the pair felt about one another. In later years, they were strapped for cash as Myra’s frequent letters imploring Fred to send money shows.

* * *

I have spent four years in the company of Myra Albert Wiggins. To date, I’ve written a little more than a dozen poems inspired by her photographs, her paintings, her husband, and her grandmother. What have I learned? That photographs can speak; they can jump out at me from museum walls and paperback books. Perhaps the impulse to create art is not bound by time or space, that although Wiggins never became famous, her work has indeed outlived her. That poetry and image can become one. At the time of her death, Myra Albert Wiggins was working on a new painting in her Seattle studio. She was a lively eighty-seven.

—By Susan Rich

Susan Rich, MFA ’96, is a poet who lives in Seattle. The poems referred to in this essay are from her most recent collection, The Alchemist’s Kitchen (White Pine Press, 2010).