Cali Bagby ’08 stood sweating in line outside the mess hall in Balad, Iraq, when the alarm signaling a mortar attack rang out between the vast concrete walls of the Army compound. “The door to the chow hall closed,” she recalls. “I had to get down in the dirt and cover my head with my hands.”

It was her first day working in a war zone.

Bagby had anticipated the danger—banked on it, even—when she signed up at age twenty-five, fresh out of college, to work as an embedded journalist with an Oregon National Guard medevac unit (C Company, 7th Battalion, 158th Aviation Regiment, based in Salem). But was she ready for war? In her senior year, she took photojournalism courses with Dan Morrison, a charismatic former war photographer and ex-Marine, who had told Bagby and her classmates, “There is no way in hell you can know if you’re going to like being a foreign correspondent until you leave the country.”

She would soon find out. She left for Balad “prepared to see horrible things,” she says.

After the first alarm sounded, Bagby remained outside the Balad mess hall in the dirt for ten minutes, panic giving way to confusion. “Inside,” she says, “I heard soldiers laughing.”

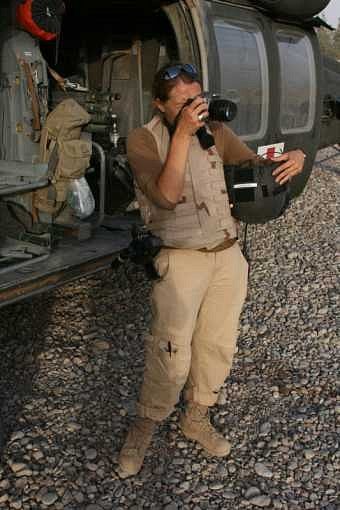

She learned quickly. Mortar attacks came often, but the compound walls offered solid protection. When she flew over Baghdad in a UH-60 Blackhawk, military regulations required her to stay strapped into a back seat, stymied by a Kevlar vest and permitted to shoot photographs only in a tiny radius through the open door. She had to deal with a daunting amount of red tape to access hospitals, which complicated her desire to tell the stories of injured soldiers and civilians. Still, she persevered.

Bagby was no stranger to adventure. She’d risked her life ice-climbing, rock-climbing, and once spending a very long night alone in a makeshift wilderness shelter with dozens of aggressive spiders. Her essay “Climbing with the Guys: Trial by Fire and Ice,” published in The Washington Post while she was still an undergraduate, told the story of her role as the lone woman on an ice-climbing expedition. Soon after graduation, she had accompanied her grandfather—an orthopedic surgeon—to Bangladesh to photograph the hospital he’d cofounded to serve the underprivileged. She returned with a heart-wrenching slide show of amputees and a desire to do what she calls “bigger work than just getting through the day and getting married.”

But what might that work look like?

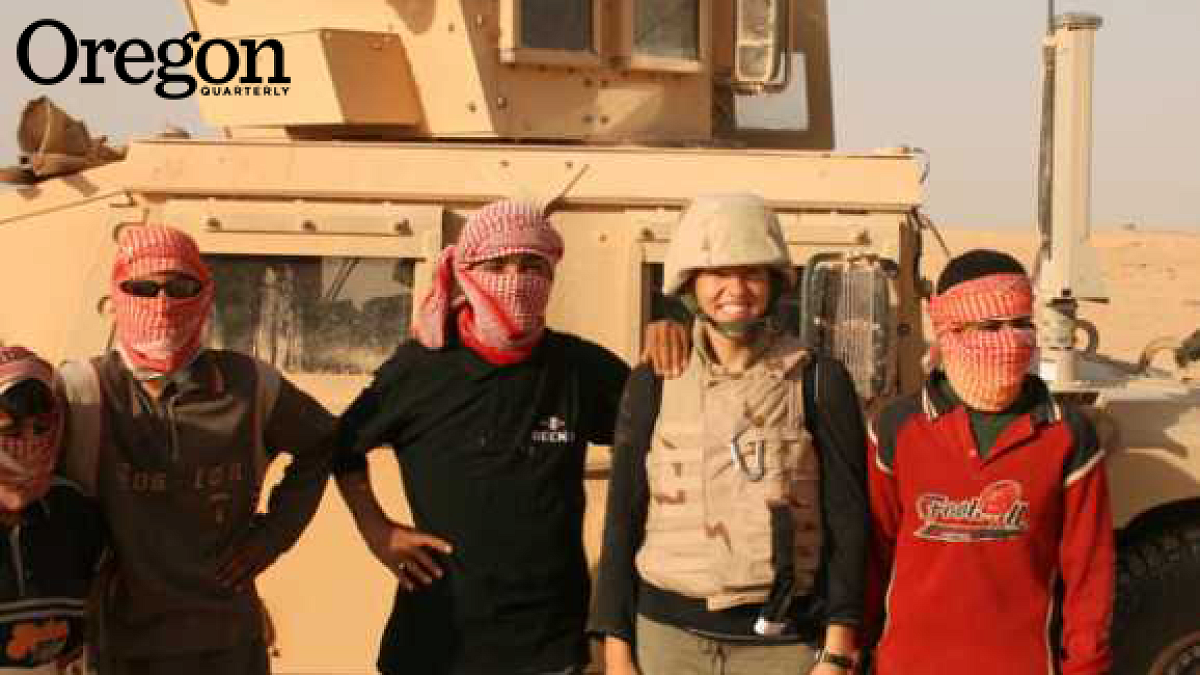

While she pondered this question, a friend, Major Geoffrey Vallee, the commander of an Oregon National Guard medevac unit, told her his unit was headed to Iraq. He invited the young journalist to go. At first, she said no, but she reconsidered, recognizing both the wartime need for “bridging the gap between Oregon citizen-soldiers and the community left behind” as well as the rare opportunity she had to “do something big” early in her career. Working with KVAL-TV in Eugene, she committed to producing multimedia reports—a combination of text, photos, and one-to-five-minute videos—about the unit during ten months in Iraq.

Immediately upon arrival in Iraq, Bagby sensed the difficulty of her mission. She was rarely allowed to leave the U.S. military compound. Internet access was limited. Some soldiers regarded her with suspicion and refused to give her information. Others insisted she write about their friends. “I felt like a fifth-grader at Valentine’s Day,” she says, “being forced to give everyone a valentine.”

She created multimedia pieces that blended stories of soldiers’ resiliency in the face of loneliness and stress with commentary on their emotional and physical wounds—pieces that still inspire parents, in particular, to send thanks. “They’ll write to me and say that it meant so much to see their son or daughter in a story,” she says, “to know that their sacrifice has been recorded.”

Some of her stories cause her to laugh self-consciously now. She filmed light pieces about soldiers making pancakes as an antidote to the chow hall’s limp vegetables and rubbery steak. But she also composed more serious reports about cleaning Blackhawks and practicing dangerous dust landings in the desert. One day, from a helicopter, she watched medevac soldiers attend to a horribly burned nineteen-year old Iraqi woman. Bagby shot a close-up photograph of the dying woman’s mother looking on. The stark image shows a deep sense of sorrow, but also a grim resignation, evoking the iconic Depression-era photographs taken by Dorothea Lange.

In August 2009, Bagby reported on twenty-two-year-old Specialist Jeremy Pierce, who lost his leg in an explosion, the first casualty of Oregon’s 41st Infantry. In her photograph for Oregonlive.com, General Paul Wentz places the Purple Heart on Pierce’s chest over a red, white, and blue quilt emblazoned with the letters “USA.” Pierce’s eyes are closed, his lips clamped shut as if to repress emotion.

Fifteen comments follow Bagby’s photo on the website—a dialogue among strangers, family, and friends pondering the meaning of service and sacrifice. Near the end of the commentary, Pierce’s wife adds her voice. “I would just like to say thank you all for your love and support. God Bless.”

Still, months in a war zone left Bagby increasingly disillusioned and depressed. Exhausted by the conflicts over her identification card, being one of few women in the compound, and struggling to make conversation in 110 degree temperatures with soldiers in the chow hall, she began eating ramen in her room and staying in bed.

The soldiers sometimes sought diversion playing Scrabble. “It felt like you weren’t just playing a game,” she says. “but doing something productive.” The familiarity of the wooden blocks imprinted with letters comforted her, even if she lost the game. “Sometimes you don’t get the right blocks. There’s nothing you can do,” Bagby says. “I’d rather play and lose than not play.”

Back in the United States after her tour, she was troubled by the thought that she’d not gotten the story she’d set out to record. “I was prepared to risk my life,” she says, “and I never did. I didn’t see anyone getting injured. I wasn’t in danger. I built up all this adrenaline for nothing.”

She holed up for several restless months at her parents’ home in Spokane, occasionally mustering the focus for a speaking engagement. Many times she sat down to write, but found herself unable to concentrate. “I didn’t know what to do next,” she says. Wary of committing to a nine-to-five job, she made plans to take a multistate bicycle trip. On a practice ride, she hit a bump and went flying.

Bagby staggered up from the sidewalk covered in blood and road rash. Soon EMTs were on the scene. She felt humiliated and pretended to be a hardcore war veteran, hoping to “save a shred of dignity.” The irony of the situation stung as much as the gravel in her wounds.

She returned to Eugene with a growing sense of despair and sought out her mentor, Dan Morrison. He’d recently gained permission to report for KVAL on a U.S. monitoring team along the Pakistani border, a rugged and unsecured area where soldiers lived in tents without electricity. Already, troops had sustained fatalities from IEDs (improvised explosive devices).

She knew she wanted to tell their stories.

“I’m coming with you,” she told Morrison.

She made arrangements to report for KVAL again and began the arduous process of negotiating visas and shopping for a Kevlar vest.

Morrison no longer refers to Bagby as his student but as his colleague. “Cali has a year of experience in a war zone,” Morrison says. “She knows what she’s doing.”

Morrison plans to stay in Afghanistan for six weeks. Bagby purchased a one-way ticket.

—By Melissa Hart