Robert Elder ’00 was in his mid-twenties and single when he began researching his book, Last Words of the Executed (University of Chicago Press, 2010), a compilation of the final statements of more than 900 convicted criminals who faced death by hanging, firing squad, electric chair, or lethal injections.

By the time he completed the book, he was thirty-three, married, and the father of one-year-old twins.

Getting to the finish line was tough, the Chicago journalist says. “I hadn’t expected to have children during [the writing of the book]. I had to spend time with people who were accused of horrific child murder, molestation, rape, and abuse. My wife, who was researching with me every step of the way, was pregnant with twins. We were having grisly, difficult conversations, and it just wasn’t pleasant.”

Elder, who has written for The New York Times, Chicago Tribune, and Salon, spent seven years searching through newspaper archives and prison records, reading through more than 6,000 written and oral recordings of executed prisoners’ “last words.” He was motivated by one of journalism’s most esteemed aspirations, to give public voice to the traditionally voiceless.

“These are society’s most dangerous, outcast members,” Elder says. “Why is it a cultural ritual to record what they say? I wanted to have a laser beam focus on that central question.”

For centuries, people’s dying statements have been recorded and revered. “They matter because they can’t be taken back,” Elder says. “Death is an experience each of us has to go through. We all wonder, ‘what does one say on the edge of oblivion?’”

The last words of those about to be executed have a particular resonance, Elder says, not only because of their circumstances but because, unlike most of us, these people know the exact time of their death and that their statements will be recorded. He was “appalled,” he says, when he realized that although these “last words” existed in archives and records, no one had formally compiled them into a book. So he set to work.

Elder chose the book’s entries to reflect a variety of people, regions, periods, ethnic backgrounds, and cultural attitudes. Entries span 350 years, from 1659 to 2009. He also included “words I read that I could not shake, things that stuck with me,” he says.

Early entries are often last words of individuals hanged for religious reasons, such as Quakers in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. “Yea, I have been in Paradise several days and now I am about to enter eternal happiness,” were the final words of Mary Dyer, executed in 1660 for disobeying a banishment decree. Wayward soldiers are also represented. “I have been among drawn swords, flying bullets, roaring cannons, amidst all which, I knew not what Fear meant: but now I have appreciations of the dreadful wrath of God, in the other World, which I am going into, my soul within me, is amazed at it,” said an unnamed military ring leader, executed in 1673 for treason and mutiny.

Most of the entries are from individuals whose names are known only to history, to specific geographical areas, or to those affected by the crimes, but some famous names made the cut, including accused witch Sarah Good, hung in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1692: “I am no more a witch than you are a wizard, and if you take away my life, God will give you blood to drink.” Ted Bundy, executed by the electric chair in 1989, is also present: “I’d like you to give my love to my family and friends.” Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh, executed in Indiana by lethal injection in 2001, didn’t leave any words of his own but left behind the poem “Invictus” by William Ernest Henley: “It matters not how strait the gate/How charged with punishments the scroll/ I am the master of my fate/I am the captain of my soul.”

Oral historian Studs Terkel, who wrote the book’s foreword, commented that what he would remember best about the book “is its poetry—the actual poetry in the speech of people at the most traumatic moment of their lives.”

Elder says he did not intend the book to take a stand on the issue of capital punishment. However, many of the soon-to-be executed used their last words to proclaim their innocence and at least one was innocent of the murder for which he was put to death. In recent years, many used their last words to rail against capital punishment and plead for the practice to be abolished.

But brief descriptions of the crimes for which each of the speakers was put to death provide essential context for their often-desperate words. Some of the crimes were the result of impulse, passion, mental illness, greed, or revenge. But others were cold-blooded and grisly: Frank Rose, executed by a Utah firing squad in 1904, shot his wife on Christmas Day and left his two-year-old son, without food or water, with his mother’s body for two days. Gordon Northcott, executed by hanging in 1930, admitted to torturing, molesting, and killing twenty young men and boys. Jason Massey, killed by lethal injection in Texas in 2001, raped, stabbed, disemboweled, decapitated, and mutilated a thirteen-year-old girl.

Initially, Elder wasn’t going to include descriptions of the crimes because he didn’t want them to divert attention from the focus of the book. But eventually, he says, “I was convinced by my wife and a couple of editors that it would give the book greater context, depth, and resonance. You can feel empathy for the person speaking, but when put in the context of the crime, it makes you feel conflicted. It creates emotional and cognitive dissonance with the reader.”

Elder visited Salem, Massachusetts, while on a recent tour promoting the book. Although the town has erected a memorial reminding people of the town’s intolerant past, the actual site where nineteen people were executed for witchcraft, Gallows Hill, is now a playground. “I was stunned it was not more of a memorial, but at least the area is going to good use,” he says. “And I like it that they don’t call it something else.”

In order to lighten his mood while writing Last Words, Elder, who has been a film critic, embarked on a second book based on interviews with thirty directors discussing the movies that made them want to be a director. Working on the book was a life saver, he says. “You can’t spend that much time on such a dark subject and keep your perspective and sanity.”

Last year, Elder was laid off from his decade-long reporting job at the Chicago Tribune, which gave him time to address ideas that had been languishing in his back pocket for years. He set up two websites asking people to send in their stories of relationship beginnings and endings. “I just wanted to do something fun, frivolous, and light as air,” he says. He is apparently graced with a journalist’s Midas touch—both www.ItWasOverWhen.com and www.ItWasLoveWhen.com went viral, and he signed a contract for two books based on the collected stories. He is now a regional editor for AOL’s www.Patch.com, a local news website covering eleven states.

Elder has been named the School of Journalism and Communication’s 2010 Eric Allen Outstanding Young Alumnus. He will be honored during the school’s Hall of Achievement dinner and reception in November 2010.

—By Alice Tallmadge, MA '87

Closer to Home . . .

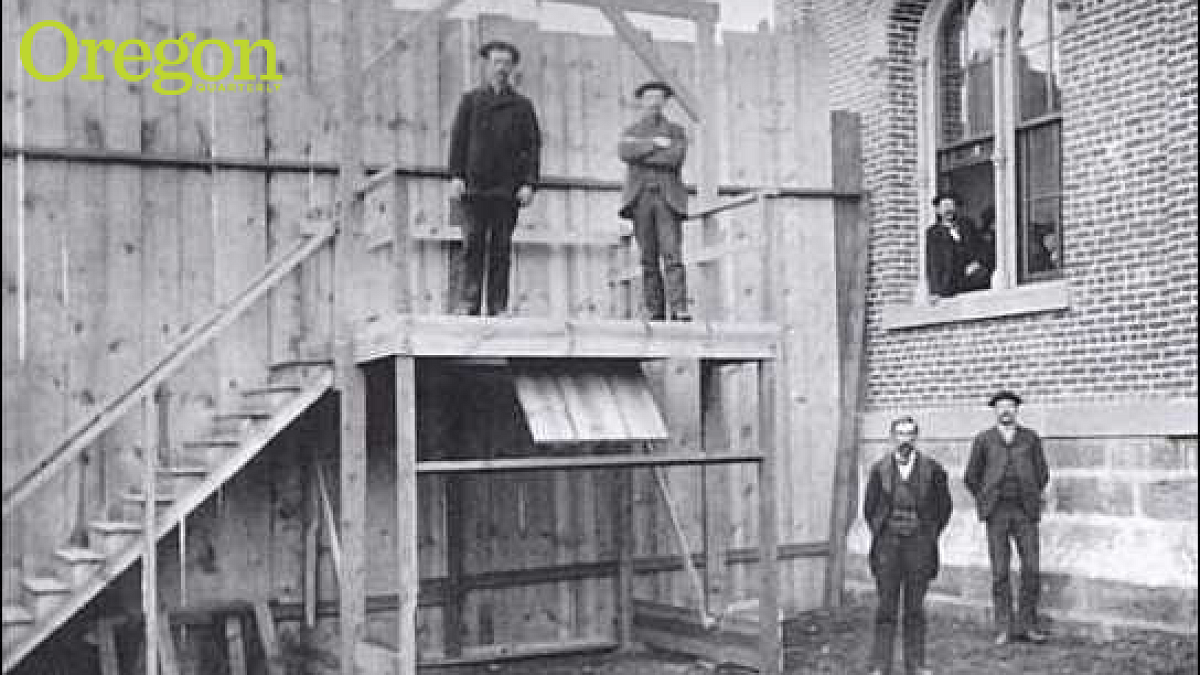

Oregon has never executed a woman, as Diane Goeres-Gardner ’71, MA ’83, found in researching her second book, Murder, Morality and Madness (Caxton Press, 2009). The book delves into the background of all eighteen Oregon women accused of murder from the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s. Goeres-Gardner combed through archives of newspapers, court documents, and police arrest records to discover the context of the women’s crimes, the judicial process the women went through, and the living conditions convicted women endured in prison.

Goeres-Gardner’s research exposed the time’s contradictory attitude toward women. The prevailing Victorian view was that women were too weak and frail of mind to vote, much less carry out such a dastardly deed as murder. On the other hand, the press and the public didn’t hesitate to excoriate some of the women before they were tried. And if a woman was sent to prison, the conditions she faced were stark and isolating. “I thought I would find women had been discriminated against,” Goeres-Gardner said, “but not how badly they were discriminated against. How cold-blooded it could be at times, how blatant and how vicious.”

And how exploitive. During that period Portland was known for being a “mecca for vice and sin.” The 1880 census listed fifty-eight prostitutes living and working in Portland. By 1912 there were more than 400 houses of prostitution on Portland’s west side. Prostitution was prosecuted, but only to a degree. Fines and payoffs to police paid for a major portion of the civic government operating in the city. Economically, bawdy houses were “a source of income to the police, the politicians, the physicians, the liquor dealers, and the municipality.”

—AT