Reed College at that time offered perhaps the best calligraphy instruction in the country. Throughout the campus, every poster, every label on every drawer, was beautifully hand calligraphed. Because I had dropped out and didn’t have to take the normal classes, I decided to take a calligraphy class to learn how to do this. I learned about serif and sans serif typefaces, about varying the amount of space between different letter combinations, about what makes great typography great. It was beautiful, historical, artistically subtle in a way that science can’t capture, and I found it fascinating. . . . [T]en years later, when we were designing the first Macintosh computer, it all came back to me. And we designed it all into the Mac. It was the first computer with beautiful typography. . . . If I had never dropped out, I would have never dropped in on this calligraphy class, and personal computers might not have the wonderful typography that they do.

—Steve Jobs

That quotation from a 2005 address by Apple’s cofounder received renewed attention when this key player in the personal computer revolution died last fall, reminding fans that his 1970s Portland sojourn paved the way for desktop publishing and much else. But how, exactly, did calligraphy come to play such a large role in a small private college in Oregon?

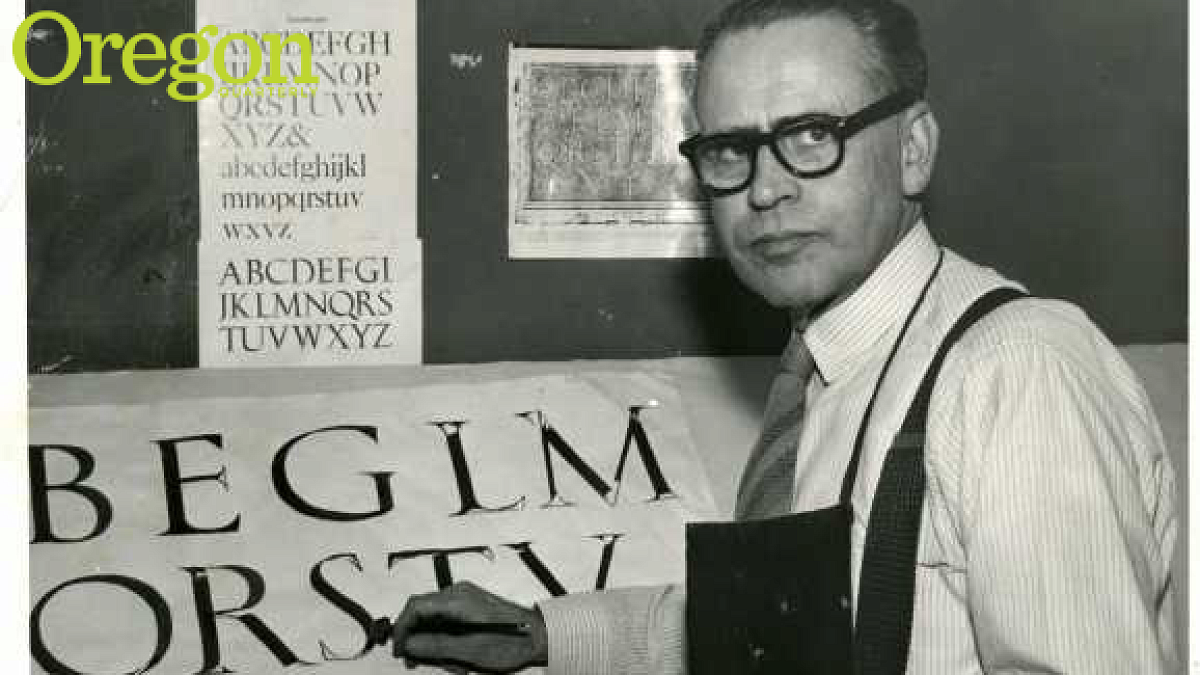

The visionary behind those classes and posters was longtime Reed College professor Lloyd Reynolds, MA ’29, whose successor, Robert Palladino, taught Jobs and hundreds of other Reed students, along with the thousands that Reynolds (1902–78) himself taught between 1929 and his retirement four decades later. “He was critical in the introduction of calligraphy to the Pacific Northwest and to the West Coast,” says his former student, Reed College special collections librarian Gay Walker.

Jobs wasn’t the only one to achieve fame beyond the esoteric world of calligraphy. Poets Gary Snyder, William Stafford, and Carolyn Kizer, composer Lou Harrison, type designer Sumner Stone, printmaker Margot Voorhies Thompson, and many other artists were deeply influenced by Reynolds and his philosophy. A recent retrospective exhibition at Reed’s Cooley Memorial Art Gallery revealed the breadth of the Oregon artist and scholar’s influence and the beauty of his art.

Reynolds’s philosophy began to take shape during his years at the UO in the 1920s. He had moved to Oregon from Minnesota with his family as a child in 1914, and even then he loved to draw, especially letters. After graduating from Portland’s Franklin High School in 1920, he earned a degree in botany and forestry from Oregon State; then, after teaching high school in Roseburg and doing some unsatisfying advertising lettering, Reynolds obtained a master’s degree in English literature from the UO. His philosophy of art and learning sprang from the writers he studied at the University. “William Blake, John Ruskin, and William Morris had become my mentors,” Reynolds wrote. “All three hated commercialism and industrialism and valued art, literature, and book-making.”

“Reynolds revered and absorbed the ideas of William Morris [who] propounded the ‘craftsman ideal,’ the belief that natural beauty, simplicity, and utility should infuse everyday life and everyday objects, and goods should be made by artisans rather than by machines,” Cooley Gallery curator and director Stephanie Snyder wrote in the exhibition catalog.

Reynolds believed that art and art- making were for everyone, not just elites. That democratic attitude fit in at Portland’s Reed College, which even then had earned a reputation for left-leaning thinking and rigorous curricula. Reed hired Reynolds to teach English and creative writing in 1929. Still, his childhood attraction to lettering wouldn’t subside. In 1934, he found a book on the history of writing and lettering. “It was like a bolt of lightning. Here was the insight I had been seeking,” he recalled later. “The only logical approach is the historical one. Learn to cut reed and quill pens and write your way through the history of the alphabet!”

Impressed by his early efforts, the English department asked Reynolds to make calligraphed bulletin board announcements. Students who encountered his strikingly elegant script asked for informal instruction, and by 1948, Reynolds was running a new workshop course in calligraphy.

His studio classes included lectures on the history of letters, design, philosophy, literature, page layout, and other contextual material. In addition, using brown, red, or black felt-tip markers, he would demonstrate each alphabet, writing on butcher paper mounted on easels, and the students would practice imitating him, over and over, learning by example. Eventually, the self-taught Reynolds would teach book design, typography, and printmaking as well, and not just at Reed, but also at Marylhurst College (now University), at the city’s art museum, and in workshops for teachers around the country.

“By the late fifties and sixties, the full impact of Reynolds’s teaching was apparent on campus,” wrote Walker, who helped curate the Cooley exhibition, in the catalog. “His classes were oversubscribed and fully attended—the art history course commonly had standing room only. . . . Everywhere were attractive hand-lettered posters, banners, and broadsides. The campus was abuzz with this beautifying functional art.”

Calligraphy was not the only way Reynolds left his mark. The Cooley Gallery exhibit demonstrated the artist’s superior printmaking skills and wood and zinc engraving, all of which he applied to book illustrations and taught in graphic arts workshops. He also designed bookplates, including one used at Reed’s Hauser Memorial Library for almost half a century, and cofounded Reed’s Champoeg Press.

Just as Reynolds retained the love of English lit he’d learned at the UO, he maintained the love of nature cultivated in his forestry studies at OSU, so Reedies in those days could sometimes spot “weathergrams”—brief texts about seasonal subjects Reynolds inscribed on the backs of used brown paper grocery sacks and hung on tree branches during the stretch between solstice and equinox. “We let a bough or branch be our publisher,” one read.

Reynolds’s reverence for nature and progressive political views stretched back for decades. Some of his late 1930s and early 1940s prints opposed American involvement in Europe’s wars. One of the darkest images in the Cooley exhibit depicts a fierce figure gazing haughtily down at the viewer. His 1954 print The Accuser was made around the same time he was ordered to testify at the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings in Portland, based on accusations that he, like many American artists and intellectuals of the time, had once been a member of the Young Communist League. Reynolds refused to answer the committee’s questions, resulting in suspension from teaching his summer course. To keep his job, he reluctantly agreed to explain his political affiliations to Reed’s president and some trustees. (Another Reed professor and close friend was fired after refusing to do so.)

The incident didn’t diminish the high regard Reynolds earned in his distinguished academic career. Governor Tom McCall ’36 appointed him Oregon’s Calligrapher Laureate in 1972. Several of the award certificates he received from arts and educational institutions appeared in the Cooley exhibit—beautifully calligraphed by his students. (The exhibit’s catalog copy is set in ITC Stone Serif, designed by Reynolds’s student Sumner Stone.)

While Steve Jobs arrived too late to take calligraphy directly from Reynolds, the master’s inspiring legacy is unmistakable; Apple’s sleek creations embody the ideals of useful beauty Jobs learned from the classes Reynolds designed. The Apple cofounder famously placed his company at the intersection of technology and liberal arts, reflecting the classroom combination of literature, history, and technique training practiced by Reynolds and Palladino.

But though he would likely have admired their user-centered usefulness and minimalist design, Reynolds himself might not have entirely approved of Jobs’s technological creations. “Since the early 1960s, a profound change in Western culture has appeared,” he wrote. “Many people have become aware of the faults in our commercial, technological culture. They are tired of being only spectators and consumers. We can make things, not just push buttons. We might not need electric toothbrushes, electric can openers, pencil sharpeners, and shoe polishers. We can use our hands. In writing something, we might use a pen and ignore the electric typewriter. Instead of boredom, joy in the making!”

—By Brett Campbell, MS ’96