More than 300 languages were spoken at the time Europeans arrived in what is now the United States. More than half of them have gone silent as US government policies of forced removal and assimilation fractured and dispersed Native American communities.

Today, Native social scientists are actively engaged in the revitalization of their cultures and languages. At the University of Oregon, teams of Native researchers are building digital archives containing historical documentation to make language knowledge available to their communities.

RELATED LINKS

Chief Warren Brainard of the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Indians, is focused on a future that could restore much of what has been lost—his tribe’s ancestral languages and the sense of culture and community rooted in them. He and other elders are supporting two linguists from their own community to carry out research for the revitalization of Hanis, Miluk, Alsea, and Siuslaw. Tribal members spend hours being interviewed, describing their upbringing, families, customs, even a story—anything that might trigger the recollection of a word or phrase that the linguists can document.

Outside the UO, efforts to preserve and revitalize languages are surging in response to a global rise in language endangerment. Governmental and private institutions, museums, and universities are partnering with tribes and Native researchers to develop dictionaries, curriculums, and other resources for teaching the next generation of Native children the languages of their people.

This reversal of fortune for his ancestors’ language is deeply gratifying for Chief Brainard. “Tribal people realize that their language and way of life is quickly disappearing,” he says, “so it’s great to have someone who will work with them to revive it.”

Gabriela Pérez Báez is a new assistant professor in linguistics at Oregon who specializes in the revitalization of indigenous languages. She is codirector of the National Breath of Life Archival Institute for Indigenous Languages, which trains Native American community researchers to navigate massive physical and digital archival repositories such as the National Anthropological Archives. The documents and other resources held in these collections are of great value for cultural and linguistic revitalization.

Pérez Báez and Breath of Life codirector Daryl Baldwin of the Myaamia Center at Miami University recently received $311,641 from the National Endowment for the Humanities to provide training to Native researchers on the use of powerful new archival software—the Indigenous Languages Digital Archive (ILDA). Users of ILDA can instantly search tens of thousands of digital records on a query.

ILDA is already making an impact. Three Native researchers at the UO Northwest Indian Language Institute working on the Nuu-wee-ya’ (new-WAY-ah) language have created an archive with more than 28,000 entries. For Siletz tribal member Carson Viles, BA ’13 (environmental studies), ILDA provides a platform to do the technical work needed to support revitalization of his ancestral language.

The software enables researchers from the tribes to choose the information important to them for a revitalization project. “Through ILDA, community researchers have control over the data on their languages and cultures,” Pérez Báez says. “There’s an element of empowerment.” She is inspired by Viles’ view of the process of language revitalization as “putting the world back together.”

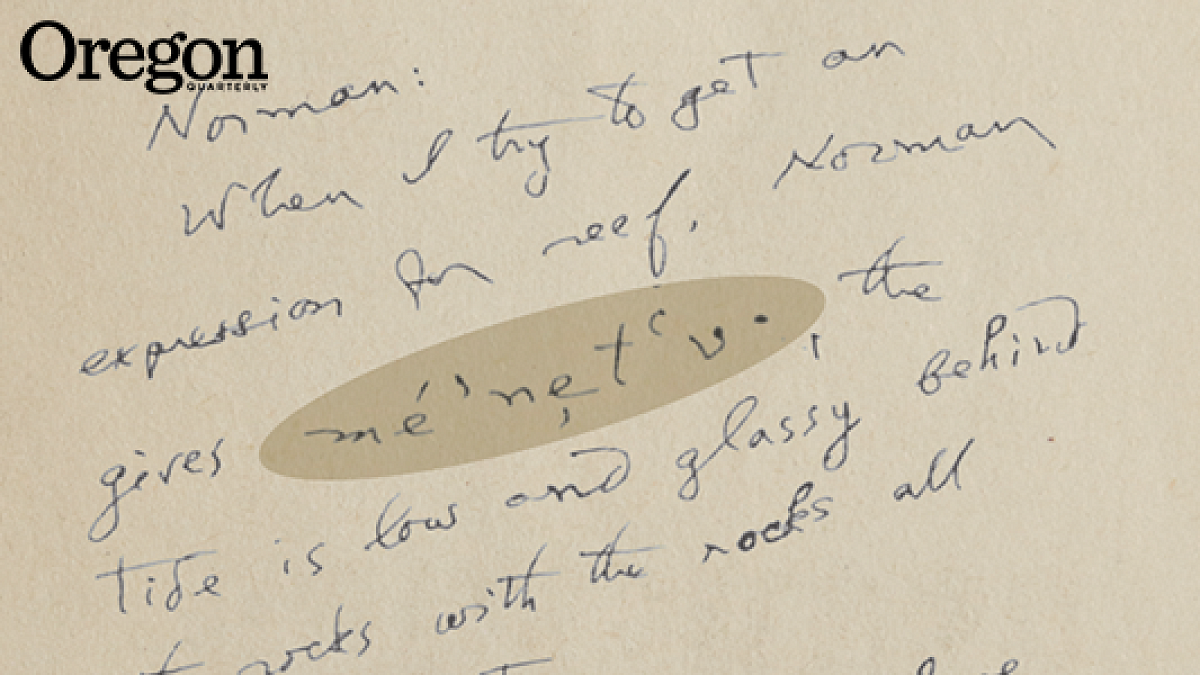

For these tribal researchers, a first contact with historical language resources can be emotional. It is often a direct ancestor who spoke in a recording or who provided the words or stories in the archival manuscripts. Sometimes, files also include photographs of old tribal members and ways of life.

UO linguistics major Enna Helms, a researcher and member of the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Indians who is working with elders on the project, has seen firsthand the impact of the project on Native people who participate.

“Our elders and their parents grew up in a time where it was really not OK to speak the language or to dance or sing our songs,” Helms says. “But the spirit is still here. We’re in this process of finding our voice again—not just in the language but in things surrounding our environment and lifeways. It’s healing.”

—By Matt Cooper, University Communications