It was the early 1970s, and Lane County parks officials and local citizens were trying to get Governor Tom McCall '36 to throw his support toward a proposal to add 3,500 acres of farmland and gravel mines to the Willamette River Greenway. McCall was less than enthusiastic, but he agreed to take a look.

A group led by county planning director Howard Buford volunteered to spend an afternoon driving McCall all over the site: up Mount Pisgah's forested flanks, along its blackberry-infested lowlands, through former floodplains armored with rock revetment and pocked with borrow pits. It was August: the creeks were dry and degraded from the hooves of cattle, the grass was parched, and cowpies littered the ground. Finally, as Buford later told it, the governor caved: "Okay," McCall conceded, "I'll buy your damned brown mountain!"

Four decades later, McCall might not recognize Howard Buford Recreation Area, better known as Buford Park, especially on a fine spring day: the creeks full and their banks lush with native vegetation, the hillsides festooned with wildflowers, the park's 20-plus miles of trails crawling with hikers. If you attended the UO, you may well have hiked to the top of 1,531-foot Mount Pisgah at least once, maybe a hundred times; dozens of locals hike it weekly, even daily. The park now hosts more than a half-million visitors a year.

Dedicated Volunteers

Buford Park has undergone a major metamorphosis in the past 20 years. Many of the improvements are due to the work of volunteers with Mount Pisgah Arboretum, the 209-acre park-within-a-park at the base of the mountain.

Stewardship of the area's remaining 2,154 acres has fallen to the Friends of Buford Park and Mount Pisgah, a citizens' group formed 25 years ago to do the work the underfunded county parks department isn't able to do—which is just about everything.

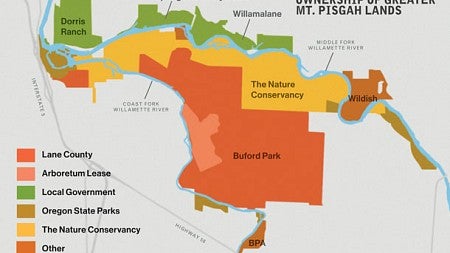

This is, in a sense, Mount Pisgah's moment, with an ambitious interpretive program in the planning at the arboretum, a major habitat restoration effort wrapping up within the bounds of Buford Park, and even more ambitious restoration projects getting underway on adjoining parcels. Buford Park is the largest piece in a mosaic of state and county parks and other conserved lands now clustered at the confluence of the Willamette's Middle and Coast Forks—the start of the Willamette River main stem. Altogether the Greater Mount Pisgah Area, as it's being called, totals some 4,700 acres, slightly smaller than Portland's celebrated Forest Park and nearly as big as Finley National Wildlife Refuge, the largest wildlife preserve in the entire Willamette Valley.

Much of the credit for this uninterrupted assemblage of conserved and connected lands goes to the Friends of Buford Park and its executive director, Chris Orsinger '84, a tall man with a boy's enthusiasm for wild land and rivers and a wonkish bent for the policymaking and politicking required to save them. "It's really satisfying having an executive director who really knows what he's doing," says Friends' board president Chaz Dutoit '89. "We've just transformed the place."

A Complex History

In 1973, the State of Oregon acquired Mount Pisgah along with four miles of Coast Fork river frontage, although the $1.5 million set aside to establish the park didn't stretch far enough to include purchase of a large piece of Middle Fork frontage owned by the Wildish family.

In 1975, the International Arboretum Association—later renamed Friends of Mount Pisgah Arboretum—signed a lease for a chunk of land at the base of Pisgah and set to work cleaning up the abandoned farm there. Lane County took over Buford Park in 1982, renaming it in honor of the county planning director who led the drive to preserve it for the public.

By 1989, the park had been in public ownership for 16 years, yet cattle still grazed freely, littering picnic areas with cowpies and intimidating hikers. Much of the landscape was choked with blackberry thickets. There wasn't much of a trail system—mostly old roads and muddy, rutted paths the cows had cut. And there was no master plan—no road map for how the park might be developed and improved. That year, a group of frequent visitors, frustrated with the condition of the park, decided to take matters into their own hands, forming the Friends of Buford Park. At their urging, the county finally terminated grazing on all but 170 acres of the park. A master plan was drawn up and adopted in 1994, calling for low-intensity recreation, protection of sensitive habitat, and restoration of degraded areas. In 1992, the Friends was formalized as a nonprofit corporation, and in 1995, Orsinger, who had been serving as board president, become the group's executive director.

Quickly the Friends' membership and budget began to grow and its accomplishments to stack up. Volunteers inventoried the mountain trails, helped develop a master trails plan, and worked with the county to rehab, regrade, and reroute some of those paths. They inventoried the plant life in the park and took steps to protect and restore the oak savannas—the area's signature ecosystem, now globally rare—as well as wetland prairies, riparian areas, and other habitat types. They arranged for a federally funded habitat study of a 25-square-mile area centered on the park, and they began implementing some of the recommendations, including reopening old river channels and reestablishing native plant species in a bend of the Coast Fork known as the South Meadow—a 20-year project that is nearly complete.

In 2000, the Friends created a native plant nursery at the north end of the park; it provides wildflowers, grasses, shrubs, and trees, not only for the Friends' own restoration projects but for other groups, such as the McKenzie River Trust. Today the Friends has 12 paid staff members and an annual budget exceeding $600,000, most of it used for habitat restoration.

The Missing Piece

Meanwhile, acquisition of the Wildish family's six miles of river frontage was never far off Orsinger's radar. It was the one that got away, "the wild heartland of the Mount Pisgah area," as he characterizes it. The habitat study the Friends arranged in the mid-'90s had highlighted benefits that would accrue for salmon and other wildlife by restoring the riparian landscape and reconnecting the gravel ponds to the river. Another study was done by the Army Corps of Engineers following the Willamette River's disastrous 1996 flood. It suggested that opening old river channels on the Wildish lands, thus allowing high water to flow over the floodplains at the confluence of the Willamette, could do even more to limit downstream damage during winter floods than could holding the water behind dams upstream.

As early as 1991, Orsinger had begun talks with the Wildish family, gauging their willingness to put those lands into conservation, if a price could be agreed upon and funding could be secured.

It only took 20 years.

Wildish had been a willing seller back in 1973 and remained one into this century, but the company had no interest in giving the land away; it was seeking fair market value. Not until 2010, after a series of statewide land-use issues were settled, did Wildish settle on a price: $23.4 million. The county didn't have that kind of money to spend. By then, however, Orsinger had contacted The Nature Conservancy (TNC), an international conservation organization experienced in handling large, complex transactions of this kind. That year, TNC became the owner of what it now calls its Willamette Confluence Preserve.

TNC has since begun planning what it expects will be a 10-year project to breach the site's artificially hardened riverbanks and reconnect its gravel ponds to the Middle Fork in an effort to restore complexity to the river and allow it to flood seasonally. Work is scheduled to start this summer. Once the land and river are back on a healthy trajectory, TNC plans to turn the land over either to the state or county parks department or another public agency willing and able to manage it for the benefit of the fish and wildlife the organization expects to have welcomed back to the site. The TNC preserve is not currently open to the public, but the Friends of Buford Park offers frequent tours.

Orsinger acknowledges that $23.4 million is a lot of money, and the habitat restoration TNC is planning might cost nearly that much again. "Why is it worth spending so much?" Orsinger poses rhetorically. "In part because it was the largest continuous ownership that was available in the floodplain on the entire Willamette River. There's no other opportunity like it, not to mention at the confluence, in a conservation opportunity area, next to a 2,300-acre natural park. Basically, it's the meat in the sandwich of a 4,700-acre natural area."

The Last Little Bit

Which makes Turtle Flats—63 weedy acres of abandoned gravel ponds behind the former BRING Recycling site west of the park, abutting the Nature Conservancy preserve—the cherry on the sundae. Lane County Waste Management bought the parcel in the 1970s for a landfill that was never built. Meanwhile, people began using it to access undeveloped, state-owned Glassbar Island, a traditional nude beach. Over time the remote, shrubby site also became infamous as a seedy hook-up venue. It's ripe for floodplain restoration and ideally situated for family-friendly recreation, but its social history makes it tricky to manage. The county's waste division has been trying to unload it since the 1990s. Lane County Parks doesn't want it. The Nature Conservancy already has its hands full. McKenzie River Trust isn't prepared to take it on.

That leaves the Friends of Buford Park and Mount Pisgah, which—for the first time in its 25-year history—is poised to become not just a guest steward but an actual landowner. By the end of this year, the group hopes to take ownership of Turtle Flats. The Friends has already begun collaborating with TNC to design the extensive habitat restoration and, ultimately, low-impact recreational development it envisions for the site.

"It's a very big deal," says Friends board president Dutoit. "There wasn't another entity that was willing to take over ownership; we're what's left. It's a crucial, small, final piece, the last piece of the puzzle to make the whole system work. With our partners and their technical expertise, and grants we can secure to do the work, we felt we could take it on."

The benefits of the conservation work going on at the Greater Mount Pisgah Area are hard to overstate, says Brian Millington, JD '06, past president of the Friends' board.

"The Eugene-Springfield population is going to have access to cleaner water, a bigger park, and a conservation area that is going to be protected in perpetuity. It will be there as the city grows, this really special and important spot. It's all going to be there for the next generation."

Change of mission, change of heart

A founder and major supporter of the arboretum regrets its change of focus.

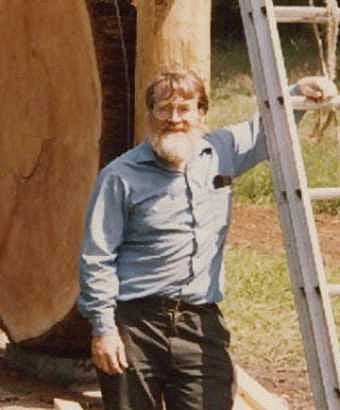

When Theodore Palmer moved to Eugene in 1970 to join the UO mathematics faculty, he vowed he would ensure that an arboretum was built in his adopted city. And not just any arboretum, but a world-class collection of trees from around the globe, artfully arranged in a natural setting—an arboretum second to none. He spent the next 40 years working toward that goal as a board member, fundraiser in chief, donor, trail builder, and puller of blackberries and Scotch broom. But while his vision never changed, the interests of the community did. Today Mount Pisgah Arboretum is thriving as a nature education center and showcase of the southern Willamette Valley ecosystem—minus its ardent, long-time cheerleader.

Palmer practically grew up in an arboretum: his father was a botanical taxonomist at Harvard University's Arnold Arboretum, North America's first public arboretum and still among the world's finest. Every Palmer family vacation—and later, Palmer's own travels—included visits to arboretums. So when Palmer, newly arrived in Eugene, learned that plans were already afoot to create, as the group's original mission statement put it, "a garden featuring plants from around the world growing together to symbolize international friendship," he threw himself into that effort. When it became apparent that a large county park was to be established on Mount Pisgah, a few minutes from town, the group jumped on it.

More experienced arboretum professionals urged Mount Pisgah Arboretum to defer planting until they had a master plan in place. As a result, by early this century few nonnative trees had been planted, aside from a grove of coast redwoods and a species rhododendron garden. But by then a new generation of board members had begun to question the arboretum's core mission. In 2012, they voted to rewrite the mission statement, taking out references to exotic tree species and focusing on education and stewardship of the site's native landscape.

Worry about the invasive potential of exotic trees was one reason given for the change in mission, though Palmer dismisses it. "The board established strict rules to deal with this concern," he says. Board member Tim King agrees with that assessment. His support for the new mission had more to do with the difficulty and expense of properly caring for a wide variety of exotic trees with varied needs, given the site's animal inhabitants, shallow soils, and long, hot summers. King should know: the UO campus, where he was grounds supervisor for 25 years, is home to some 3,000 trees representing more than 500 species. "When I joined the board in 2001, I always had the idea that an arboretum was a collection of trees from around the world," King says, "but you can find quite a few around the U.S. and the world that are dedicated to native species only; it's kind of a trend."

Arboretum board president Anne Forrestel is not so quick to dismiss the potential harm from nonnative tree species on the riverside site, particularly given the habitat restoration efforts under way in the rest of Buford Park and the adjacent Nature Conservancy property. "Scientific evidence has become so much clearer about what happens when you tamper with native ecosystems," says Forrestel, a senior instructor at UO's Lundquist College of Business. As part of its decision-making process, the arboretum posted a poll on its website, drawing some 350 comments. "More than 70 percent of them advocated changing mission to showcase our native ecosystem," Forrestel says. That majority included virtually the entire UO scientific community, she says, as well as the Friends of Buford Park "and many, many individuals in the community." Especially given the impending restoration of the former Wildish lands, "to have, in the middle of that, 200 acres where we're going to bring in trees from all over the world makes no sense."

"Without Theodore, we wouldn't be where we are," Forrestel adds. "I joined the board because of Theodore. I was so inspired by him." But the original vision for the arboretum is now 40 years old. The world has changed, she says, and it is important that the arboretum keep up with those changes.

Palmer has left the board and is no longer volunteering for the arboretum in any capacity. When asked, he still encourages others to support it. "I think the arboretum is doing a good thing in town, bringing children out to spend time in nature," he says. It is that education mission that the board is now focused on. Fundraising has begun for an ambitious interpretive program that will highlight each of the eight habitat types found within the arboretum, including the installation of a bird blind made of woven branches at the Water Garden.

Palmer hasn't entirely lost hope that his vision for the arboretum might someday be revived, but he doesn't expect it will be in his lifetime. The change in mission, the professor emeritus says, has broken his heart.

—By Bonnie Henderson '79, MA '85