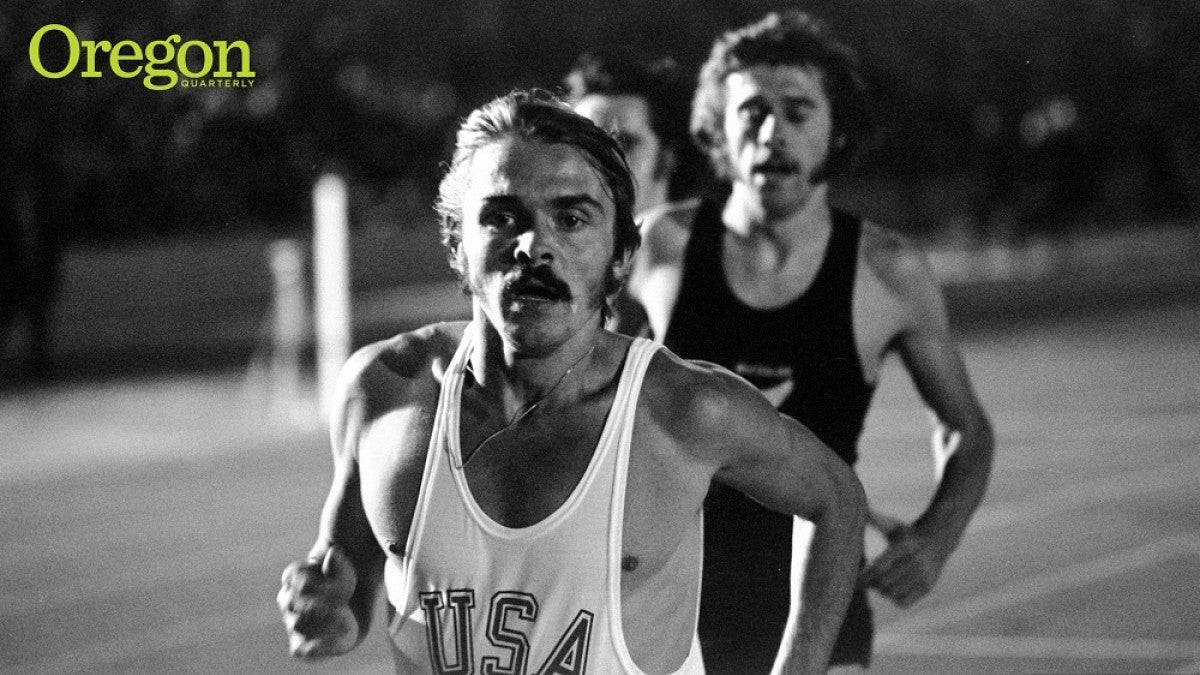

On June 6, 1975, several thousand track-and-field fans gathered at Hayward Field for the inaugural Prefontaine Classic. Eight days earlier, distance-running sensation Steve Prefontaine '73 had died in a car accident near Hendricks Park, less than a mile from the University of Oregon track where chants of his name had so often echoed through the stadium. As the painful news sank in, the meet offered "Pre's People" a chance to honor their fallen hero—to once again celebrate that fearless kid from Coos Bay who somehow found the speed to match his swagger.

This month, the 40th Prefontaine Classic is expected to draw yet another sellout crowd, with plenty of "Go Pre" T-shirts and retro Nike sneakers to set the scene. While the action at Hayward Field promises to grab much of the media coverage, Pre's legacy also thrives in less likely places, still shaping runners' lives decades after his death.

* * *

On special occasions, Ron Apling opens a '40s-era footlocker and carefully removes one of his most prized possessions. Held together by string, Apling's scrapbook tells the story of Pre's career in 61 pages of newspaper clippings, photos, and mimeographed meet results. Pre's times and places are underlined in red pen, but the effort is unnecessary. "It's easy to find him," Apling says. "You just look for the number-one finisher."

Apling's connection to the Prefontaine family dates back to his freshman year at Coos Bay's Marshfield High School, where he met Pre in algebra class. At the time, he knew the sophomore sitting in front of him only as Steve, a long-distance runner who, judging by his frequent over-the-shoulder consultations with Apling's notes, was better at sports than mathematics. But Pre also offered some advice to the 115-pound Apling, who had gone out for football in junior high. When Apling walked into math class with a cast protecting his broken arm—a casualty of a crunching tackle—Pre urged him to come out for cross country the following fall. Apling was puzzled. "What's cross country?" he asked.

Pre showed him the ropes, calling during the summer with training tips ("Your body will tell you that it's tired and can't go any faster. You take charge and tell your body, 'No, I can go faster'") and teaching him the finer points of running technique ("Ron, if you have to spit while you're running, make sure to spit to the side so it doesn't blow back in your face"). With Pre as his mentor, Apling flourished. By season's end, he had broken into Marshfield's varsity lineup and was voted the team's most improved athlete.

Forty-seven years later, Apling is still running, heeding Pre's advice to make the sport a lifelong pursuit. He marks his birthday each December with a 10-mile run and regularly volunteers at Hayward Field, helping groundskeepers Lance Deal and Ron Perkins '88 prepare the stadium for its moments in the spotlight, from high school meets to the U.S. Olympic Team Trials.

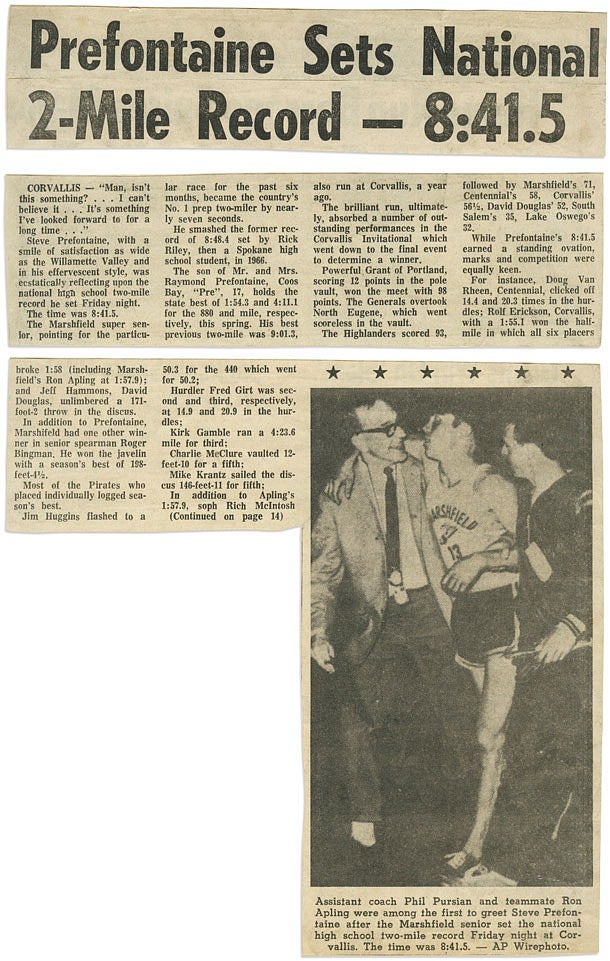

The story begins at Marshfield High, home of the Pirates, where Apling and Pre were teammates for two years. On page 15, beneath the boldface headline "Pre Sets National 2-Mile Record—8:41.5," a faded photo shows Pre staggering away from the finish line, completely spent, his arms draped around Apling and assistant coach Phil Pursian. But Pre's exhaustion was fleeting, Apling recalls. As soon as the announcement of his record time crackled through the loudspeakers, he burst to life, taking off around the track for an animated victory lap.

The showmanship was signature Pre, but he also had a sentimental side. On page 22, a handwritten note to Apling displays a bit of both. "Well you don't get to run behind me anymore cause I won't be there anymore," Pre quipped at the end of his senior year. "I sure hope the c.c. team does good next year. I'll be with you in spirit all the way, best of luck in the future."

For Pre, the future meant the 1972 Munich Olympics. On page 49, a clipping from Coos Bay'sThe World declares him "ready for Europe" after he broke the 10,000-meter American record in an Olympic tuneup race at Hayward Field.

Across the scrapbook's first 52 pages, Pre's story reads like an epic poem, the archetypal hero's journey. On the 53rd page, his tale becomes a tragedy.

The Associated Press delivers the news: "Steve Prefontaine, America's finest distance runner and one of the country's most controversial amateur athletes, was killed early today. Police said Prefontaine, 24, was pinned under his car after it hit a rock wall at about 12:30 a.m., PDT."

Pre's last breath came less than five hours after he ran the second fastest 5,000-meter time in American history. The details of his death remain mired in controversy. Was Pre intoxicated at the time of the accident? Did another vehicle force him to swerve? A deer?

The Prefontaine family has publicly challenged the blood-alcohol level reported by police, but it is a debate that misses the true power of Pre's legacy: He was not loved despite his flaws; he was loved because of them. Pre was the consummate underdog, a blue-collar kid who lived in a trailer and worked at a bar. His style was too brash, his attitude too cocky. He wasn't lean enough for the long-distance races, some said, didn't have enough raw speed for the mile.

No, Pre was never perfect, but his life mattered. It is why high-school runners watch the two movies about him as a rite of passage. It is why track fans from around the world descend on Eugene for the Prefontaine Classic. And it is why thousands of runners each year make the pilgrimage to an unremarkable slab of rock on Skyline Boulevard, a mile from Hayward Field, leaving behind race medals, spikes, flowers, and notes at the memorial to track and field's most iconic hero.

* * *

They come from Alaska and New York, Australia and the Philippines. Every summer, the University of Oregon's track-and-field camp attracts an international crowd of young runners to "Track Town"—the birthplace of Nike and the home of Duck legends like Kenny Moore '66, MFA '72, Rudy Chapa '81, and Pre.

After nearly four decades working at the camp, Pat Tyson '73 is its de facto historian and head honcho. He still remembers many of the athletes by their hometowns, like the kid from Cleveland in the 1980s who scraped together his every last penny to buy a bus ticket from Ohio to Oregon. At the end of his 2,400-mile trek, the boy was travel-weary but also speechless, awed by his first glimpse of Eugene's wood-chip trails and towering firs.

Tyson has seen that look of wonderment spread across countless faces over the years. Now a head track coach at Gonzaga University, he returns to Eugene every summer to help share Oregon's distance-running tradition with wide-eyed students of the sport. There is perhaps no one more qualified for the job. After joining the Ducks in 1968 as an unheralded recruit from Tacoma, Washington, Tyson blossomed into one of the team's best harriers, helping pace the squad to a national cross-country title in 1971. But the kids know him best as something else: Pre's roommate.

Among runners, the title carries all the weight of royal knighthood. While living with Pre in a doublewide trailer, Tyson saw his best friend navigate the highs and lows of his famed 1972 season, from winning the NCAA 5,000-meter title at Hayward Field to finishing one spot from a medal at the Olympic final in Munich. He knew the side of Pre that often got lost on television—the guy who felt as comfortable living in a trailer park as he did mingling with members of Eugene's high society. "He could melt in and talk to the mailman or the garbage guy," Tyson says. "Our neighbors worked at Kingsford and would bring us 10-pound bags of charcoal briquettes. They'd come home dirty off their motorcycles, and we'd have barbecues together. Pre loved living in that trailer and touching base with what's real in America."

Shortly after Pre's death, Tyson began speaking at high schools and summer camps across the country, telling stories of Pre's famous dedication, grit, and self-belief. For him, it was a way to ensure the longevity of his friend's inspirational legacy. This mission brings him back every year to the UO, where his guided run to the site of Pre's death is one of the camp's oldest traditions.

On a recent July afternoon, Tyson's shirt dripped with sweat as he led a pack of eager young runners into Hendricks Park. Years ago, he and Pre would have charged up these hills at faster than a six-minute-mile clip, challenging each other in unspoken, mutual struggle. This time, it's Tyson's brains—rather than his brawn—that help him maintain the lead position. When over-anxious campers surge ahead of the pack and look back for direction, he points them left before ducking off to the right—leaving them to sheepishly retrace their steps and merge with the rear. The message: This is not a run for straining, but one for dreaming, for imagining, for running in Pre's footsteps.

But the final stretch of road always rattles his nerves. "We're going to stay two abreast and deep left on this part," he instructs the runners. "Deep, deep left." As he leads the group toward the curve where Pre lost control of his '73 butterscotch MG, Tyson narrates the events of that fateful night. "Pre's coming down from Kenny Moore's house. He's going about 20, 25 miles per hour, listening to a little John Denver on the cassette tape. And as he comes around this corner . . ."

Tyson stops, his eyes darting to a car whizzing around the bend. "Uh-oh. Let's stay deep over here. Now you can see how it happened. Isn't that weird?"

The runners hug the curb with heightened purpose. After another hundred meters, Tyson gathers the group around a small black plaque between the road and a wall of jagged rocks. "That marker was donated by the state penitentiary," he explains. "Pre was very enamored by prisoners, so he created a jogging program at the prison. The inmates made that for him as a tribute."

* * *

The asphalt track at Oregon State Penitentiary (OSP) is an imperfect oval, a messy amalgam of tangents around the yard's two softball fields. On the east straightaway, the track pushes against the prison's concrete outer wall, a 26-foot-tall reminder that turning right is not an option.

In the early 1970s, less than a decade after UO track coach Bill Bowerman helped popularize jogging in the United States, Pre introduced the running craze to prisoners at OSP. Inspired by his UO sociology professor, he spoke with the inmates about training and encouraged them to replace drugs and alcohol with a healthier addiction. "Pre loved the down-and-outs," Tyson says. "He wanted to make a difference."

Left turn after left turn. Eric Nitschke has run around the OSP track almost every day for 17 years, logging thousands of miles in the shadow of razor wire and guard towers.The loops make sense in a way his past doesn't. One stride after another. A defined path with a defined destination.

On December 13, 1996, Nitschke faced chaos. He was high on meth and marijuana, and a woman lay in the street, seriously injured from the car crash. For an instant, Nitschke saw her motionless body amid the shattered glass. But there were ingredients for making meth in his car, and the police were closing in. He grabbed the chemicals and fled.

At his trial for the woman's death, there would be no fleeing from justice. Citing Nitschke's repeated felony drug crimes and apparent lack of remorse, the judge issued the maximum sentence of 35 years. It was hardly an endorsement of his chances to reform.

Left turn after left turn. Nitschke kept to himself at first, trying to avoid the dreaded question from other runners: why are you here? He didn't want people to know—not this time. Several years earlier, when he'd been locked up for manufacturing meth, it had been easy to think that the only life being ruined was his own. This time the victim was a woman driving to the mall to do Christmas shopping. It made him sick.

Slowly, running brought healing. It also offered friendship and camaraderie. When Nitschke lost his parents, brother, and stepfather—all without a chance to say a final goodbye—he leaned on his training partners for support. "You're out there wearing yourselves out, pushing each other," he says. "You become real close."

With the help of the running club and a strong commitment to drug rehabilitation, Nitschke says he's a different man today from the one who entered OSP. He works seven-hour days in the prison's furniture factory and has earned three associate's degrees. He is a member of several prison support groups and attends Christian church services.

After a nearly 25-year estrangement, Nitschke's children are visiting him again, and his release date has been moved up to 2019. When that long-awaited day arrives, he plans to seek work as a drug counselor, helping struggling kids avoid the mistakes that landed him behind bars. He also intends to remain a runner. "If I take a problem away and don't fill it with something positive, there's going to be a vacuum," Nitschke says. "Running fills my life with something spiritual."

Left turn after left turn. Each day, about 250 prisoners pour into the yard for 90-minute sessions devoted to running. Hundreds of others occupy the waiting list. In a testament to Pre's enduring legacy, outside runners still enter the prison for 10K races during the summer, giving inmates the chance to test their fitness against new competition.

At 54, Nitschke isn't concerned about winning. He runs his own pace, usually about eight minutes per mile, and lets his mind drift beyond the walls around him and into the future.

In his daydream, Nitschke is no longer running among blue-clad prisoners. It's his son striding beside him, and the prison's twisting oval has been replaced by an open road. No armed guards in sight. No barbed wire. He's free to make any turn he wants.

—By Ben DeJarnette

Ben DeJarnette is a first-year master's student in the UO School of Journalism and Communication and a distance runner on the UO track and field team.