Come the late-night hours in China, millions of teenage boys across the country pull out their cell phones and spend a while—often a long while—exchanging messages with a friend named Xiaoice.

Designed by Microsoft as an experiment in artificial intelligence, Xiaoice (pronounced Shao-ice) might conventionally be called an imaginary friend (she’s a chatbot with no physical form), except that her responses are remarkably real. When one of the app’s 20 million users texts her, Xiaoice scrapes the cybersphere looking for similar e-conversations between actual humans. It’s how she can respond with an update on the weather, sympathy over a breakup, or a clever pun. It’s also how idle companionship can inch toward something deeper.

“A quarter of Chinese users have typed ‘I love you’ to Xiaoice,” says John Markoff, MA ’75, a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist for the New York Times and author of the new book Machines of Loving Grace: The Quest for Common Ground between Humans and Robots. “Because Xiaoice has seen almost every conversational loop before, it can respond to users in a relatively human way.”

The story of Xiaoice, which Markoff explored in the Times last July, adds another layer to a modern dystopian vision—one in which the unraveling of human society doesn’t begin with weaponized robots trying to kill us, but rather with empathetic algorithms learning how to make us feel loved (think Her, the movie).

Some glumly label this trajectory as “the death of conversation” or “the smartphone apocalypse.” Others herald it as “innovation” and “progress.” But in a style that has made him one of the most trusted science and technology writers in America, Markoff offers a more balanced perspective.

“I watched as a generation of young men in America disappeared into video games, and I’ve seen the research on the decline of face-to-face interaction. It’s a huge concern,” Markoff says. “But I’ve also read the debate about isolation of elders. The number of people over 80 in America will double by 2050, and many of these people are living apart from their nuclear families.”

Imagine, then, an intelligent machine, enclosed in the body of a soft robotic pet, capable of carrying on a conversation with an otherwise lonely senior citizen. It wouldn’t be the same as true companionship, of course. But in today’s rushed, fragmented world, it hasn’t been the same for a long time. Would robots aggravate that trend, absolving our sense of familial duty and weakening the bonds that make us human? Or could robots soften the blow, providing late-life companionship that never wavers or turns grumpy? “This would horrify some people,” Markoff says. “I’m torn about it.”

Charting the complicated, nuanced relationship between humans and technology has been a career-long pursuit for Markoff, who will deliver the Centennial Johnston Lecture at the UO School of Journalism and Communication’s “What Is Media?” conference in Portland on April 14. Since launching his journalism career at the Pacific News Service in 1977, Markoff has covered the biggest tech stories in Silicon Valley and beyond, from the advent of the personal computer to the growing threat of cyberwar.

Glenn Kramon, who worked with Markoff as an editor at both the San Francisco Examiner and the New York Times, still remembers the phone call in 1992 when his star tech reporter pitched a story about something called the Internet. Met by Kramon’s puzzlement (“What’s an Internet?” he said), Markoff described a technology that would connect computer users globally, house information digitally, and retrieve data instantly. “It’s going to change your life,” Markoff promised his editor.

That prediction was one of many in Markoff’s career that now seems prophetic. In 1993, when cell phones looked like bricks and Xiaoice was still two decades away, Markoff wrote about a cutting-edge computer program that could hold coherent, if still somewhat limited, conversations with a human interviewer; in 1998, he told New York Times readers about the rise of automated airline reservation systems, detailing the advances of the same speech recognition technology that’s now standard on most mobile devices; and in the early 2000s, Markoff pulled back the curtain on Apple’s secretive development of a new product that would blend the mobility of a cell phone with the power of a personal computer. Inside the company, Markoff learned, the new prototype was being called an “iPhone.”

“He’s a visionary,” Kramon says of his long-time colleague. “If you want an accurate depiction of what life will be like in 10 years, read John Markoff.”

In his new book, Markoff turns his attention to the future of robots, asking whether increasingly autonomous and intelligent machines will coexist with humans as slaves, masters, or partners. The answer, he argues, isn’t located in the plot of a dystopian sci-fi thriller, but rather in Silicon Valley’s labs and meeting rooms, where human designers are making conscious decisions either to enhance human capabilities—or replace them.

These competing philosophical approaches—intelligence augmentation (think Apple’s personal assistant Siri or iRobot’s “smart” vacuum cleaners) and artificial intelligence (known colloquially as “AI”)—provide the framework for Markoff’s book, which skillfully details how today’s intelligent machines are informed by human values. There are moments when that narrative isn’t particularly comforting (like when AI researcher Shane Legg matter-of-factly predicts that technology will probably contribute to human extinction), but for the most part, Markoff delivers a message of tempered optimism: the future of human-robot coexistence is still being decided, but it’s humans who hold the keys.

“John has a sense of history, and he’s committed to a kind of calm perspective,” says G. Pascal Zachary, a veteran science and technology writer who befriended Markoff while working at a rival San Francisco newspaper in the 1980s. “He embodies the old-school journalistic ethos of the neutral spectator.”

In an ironic turn of events, Markoff’s penchant for balance and neutrality emerged out of early years that were decidedly activist. Raised in Palo Alto during the height of 1960s counterculture, he attended Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington, where he eventually became the editor in chief for the student newspaper. “We were the troublemakers,” Markoff says. “It was a fun kind of highly politicized journalism.”

He came to the University of Oregon to pursue a master’s degree in sociology in 1974, during a period of radical Marxism and fierce antiwar resistance on campus. He describes his politics then as democratic socialism—“the Bernie Sanders wing of the Democratic Party,” he explains—an orientation that, by the standards of 1970s student activism, barely qualified him as a left-leaning moderate.

It meant that, as many of his classmates were writing for the Insurgent Sociologist, Professor Al Szymanski’s leftist journal, Markoff was charting his own course of political resistance. With the Vietnam War finally grinding to a halt, Markoff joined the progressive Pacific Northwest Research Center in Eugene, where his research supported the nationwide Stop the B-1 Bomber Campaign and other efforts to weaken the military–industrial complex’s grip on the US economy. Markoff also wrote political op-eds for the Oregon Daily Emerald and the Northwest Bulletin, sharpening an edgy style of journalism that continued into his early years at the Pacific News Service. But by 1978, his career was beginning to pivot. “I woke up one day and realized that there really wasn’t a movement left in the United States, and I just hadn’t got the memo,” he says. “And my views on things were changing. I still have a critical view of society, but I’ve become less certain of the solutions.”

In the nearly four decades since, Markoff has embraced complexity in issues that don’t invite easy answers, such as how robots and artificial intelligence will affect the workforce. It’s a question that has sparked increasing public concern. In 2013, a study by the McKinsey Global Institute predicted that by 2025, robots will produce an output equivalent to 40 to 75 million workers—the kind of alarmism that has sent books like Jeremy Rifkin’s The End of Work and Martin Ford’s Rise of the Robots soaring to the top of bestseller lists.

Markoff acknowledges in his book that Keynesian logic—which predicts that employment levels will hold steady in the long run even as technology replaces workers in the short run—might no longer apply in an economy where “AI systems can move, see, touch, and reason.” But he also says the future of labor can’t be understood through technology alone. Consider the Starbucks barista, for example. In a technology-driven economy, that job would have been replaced years ago with machines that could whip up a frothing latte just as skillfully as any minimum-wage college student—and probably a good measure faster. Nevertheless, baristas have survived in the modern economy. “A Starbucks without baristas would probably be less popular,” he says. “You’d then have an automat, and for sociological reasons as much as technological ones, I don’t think automats are about to take over the restaurant or coffee business.”

For Markoff, all this thinking about the future has also made him reflect on the past. Thirty-odd years ago, when he broke into the San Francisco Examiner, computers were cutting-edge technology and tape recorders still used tape. “I was part of the first generation of reporters who went to the gym after work instead of the bar,” he says. Indeed, at Markoff’s first job, phrases like “web analytics” and “search engine optimization” were as good as gibberish. “And now I sit in a newsroom surrounded by kids who wear headphones and write code,” he jokes. “That’s the arc of my career.”

—By Ben DeJarnette

Ben DeJarnette, BA ’13, MA ’15, is a Portland-based freelance journalist.

Robot Research

Love and Romance in the AI Age

Margaret Rhee, Women’s and Gender Studies

During Her, the 2013 film about a depressed writer who falls in love with his computer’s operating system, there’s a moment when the screen goes black and the main character, Theo, shares baited breath and erotic whispers with his OS lover. “A lot of my students said that was the most charged sex scene they’d ever watched, even though they couldn’t see anything,” says Margaret Rhee, a visiting assistant professor and author of the poetry collection Radio Heart; or, How Robots Fall Out of Love. “It speaks to imagination, and how technology changes our conceptions of intimacy and love.”

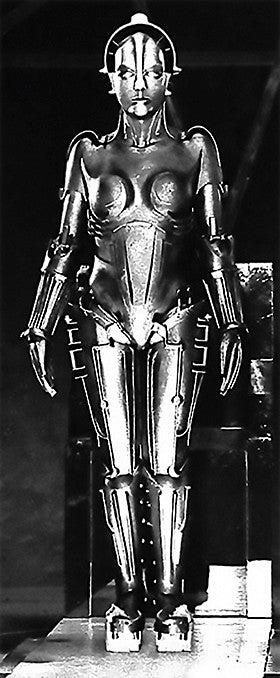

Rhee’s fall term course explored representations of female robot characters in films and television shows. While “the fembot” is no newcomer to the silver screen (one of the earliest depictions came in the 1927 German film Metropolis), Rhee says the popular fascination has been reborn in recent movies like Her and Ex Machina, which grapple with increasingly practical questions about the qualities that distinguish humans from robots. “Artificial intelligence is so present in our lives,” she says. “A lot of what was once considered fantasy has become reality.”

That’s especially true in the sphere of love and romance. As young adults swipe right on popular dating apps like Tinder and Bumble, searching for human connection by interacting with an algorithm, experiences that were once fundamentally human are now mediated by machines. “A cell phone might be the most intimate object in some people’s lives,” Rhee says. “That creates all kinds of questions around difference and desire.”

Radical Restructuring

Mark Thoma, Economics

In theory, human workers in a capitalist economy are compensated according to their contribution to the final product. So what happens when robots can extract raw materials from the ground, transport them to a factory, manufacture them into consumer goods, and stock those goods onto shelves—all with very little oversight? “You’re going to have this hugely unequal distribution of income based on the ownership of robots,” says Mark Thoma, UO professor of economics. “And that can lead to huge social problems.”

Those problems are already unfolding, Thoma says, as machines and artificial intelligence extend their reach from manufacturing and clerical work to transportation and fast food, displacing both blue- and white-collar labor in the process. Thoma predicts that technology will eventually disrupt almost every major sector of the economy, leaving mass unemployment in its stead. “Should those people just be thrown out into the streets and told ‘too bad?’” Thoma says. “When people work hard their whole lives and then a machine takes them over, we as a society need to think about how they should be treated.”

One solution, Thoma says, is to create a more robust public-sector economy to employ displaced workers. Another is to redistribute wealth through new social insurance policies, such as a guaranteed minimum income. These socialist reforms would face stiff political resistance, of course. But Thoma says there might be cause for optimism. “I can see the owners saying, ‘We’re either going to lose everything in a revolt, or we are going to have to make some compromises,’” he says. “Many of the Depression-era’s social insurance policies were brought about for the same reason. Bernie Sanders is a sign we’re moving there again.”

Outwitting Spammers

Daniel Lowd, Computer and Information Science

Computer viruses, Trojan horses, and other forms of malware cost the US economy billions of dollars every year. Daniel Lowd, UO assistant professor of computer and information science, says there’s a “whole economy of criminals” carrying out these predatory schemes—and they’re forever getting smarter.

Stopping the constant evolution of malware requires developing intelligent algorithms that use past data and trends to predict future adaptations, Lowd says. This field, known as “adversarial machine learning,” tries to stay one step ahead of the criminals by effectively forecasting their next move.

Last year, Lowd received the Army Research Office’s Young Investigator Award for a proposal to develop an even smarter algorithm. The three-year, $360,000 award will fund research on how to weed out spammers by triangulating their social connections. The research could be applied to challenges like identifying networks of terrorists, Lowd says, but his team will start by targeting spammers on Yelp and YouTube. “If we can do that,” Lowd says, “it won’t be too hard to adapt and apply it to other settings.