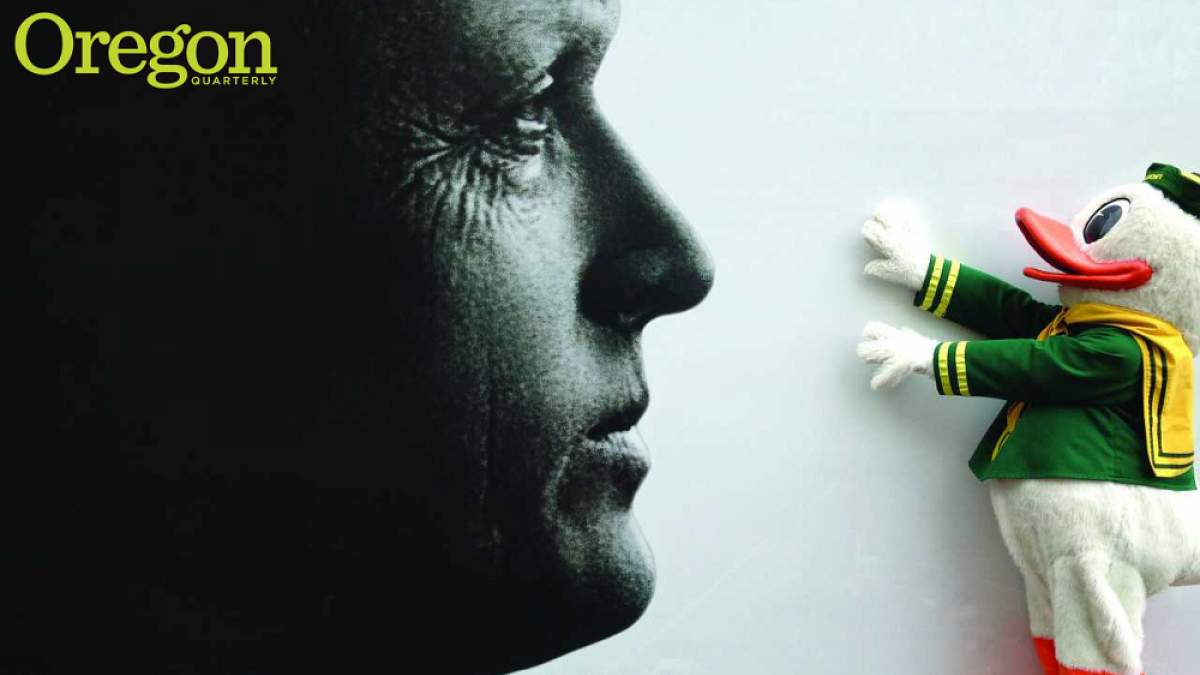

Without saying a word, he controls a crowd of thousands with a wave of his hand or a nod of his neon orange beak. He’s got a squat physique and eyes that can melt the stoniest of hearts, but he demands respect from the burliest guys in the stands. Most college fans applaud their mascots, but Oregon fans’ delight in the Duck takes that allegiance up a notch into a stratosphere that’s not quite worship, but close.

For more than six decades, fans have stuck by the Duck through thick and thin, and there has been some thin. Followers of the Duck may recall its infamous 2007 spat with the University of Houston’s Cougar mascot, Shasta. The dustup at the Autzen Stadium season opener began with chest shoves and evolved into a twenty-second wrestling match that received 1.6 million hits on YouTube, and that Lost Letterman’s blog described as “the Fight of the Century, Ali-Frazier II, and the Thrilla in Manila all rolled into one.”

Well, turns out it was a bit of a canard.

The tussle in the first half was real. The Duck didn’t like it that Shasta also did pushups after touchdowns and field goals. Maybe there was some trash quack. Either way, the Duck got his feathers in a bunch and got pushy with the cougar. Megan Robertson, now the University’s director of promotions and gameday experience, was the one who pulled them apart. “The Duck was not happy being taunted by another mascot,” she says. “There was actual anger there.”

But the flap in the second half? All for show, she says. During halftime, “they decided it would be funny to do a wrestling-type thing, with no real contact. Fake, but grand and big.” Unfortunately, the mascots didn’t tell anyone about the ruse, and it ended up ruffling some higher-up Duck down. “We had a lengthy discussion afterwards,” Robertson says. “It was not the personality we wanted our Duck to have.”

The fabled flap typifies much of the Duck’s history and evolution as the University’s mascot: a feint here, a dodge there, hyperbole that became history, a quirk that became a major quack. However he made it, today the Duck is close to the top of the college mascot heap, despite being a singularly odd fellow to be responsible for revving up sports crowds to a frenzied pitch. He doesn’t have a fang to his name. He waddles instead of swaggers. His soft paunch hints at too much bread and not enough brawn.

No matter. He’s the Duck, and fans love him. He also scores high in popularity polls. In 2011, the Huffington Post College blog ranked the Duck number one among all college mascots; Fox Sports put him at number twelve. ESPN’s camera loves the big-eyed guy and he’s been chosen to compete in the Capitol One mascot contest two years in a row.

“There’s something about the Duck that endears people to him,” says Matt Dyste, director of marketing and brand management for the University. “He’s a little feisty, a little loveable. He crosses the spectrum.”

The Duck, history has it, didn’t start out as the Duck at all. Not even as the Donald. He first showed up in the 1920s and ’30s as a side note, a one-syllable nickname that allowed sports writers to bypass the clumsier term Webfoots, which the UO student body had voted in as team name in 1926 and again in 1932, choosing it over tougher-sounding monikers such as the Pioneers, Wolves, Lumberjacks, Trappers, and Yellow Jackets.

“Why should a fighting football team, a brilliant basketball five, or other combinations be saddled with the name of a bird that is noteworthy only for its ability to shed water?” railed Oregon Daily Emerald sports editor Harold Mangum during the fractious naming debate. “It’s like lining a runner’s shoes with lead and expecting him to break records.”

Lore has it that as far back as the 1920s, fraternity fellows began escorting a series of live ducks to the football field, dubbing each one “Puddles.” Donald, the cartoon duck created by Walt Disney, made his first public appearance in the 1934 cartoon “The Wise Little Hen,” playing an idler in a sailor suit who’d rather dance than work in the fields.

In the ensuing decade, University students took to the Donald image as, yes, ducks to water. Cartoon images from Oregana, the University’s yearbook, show a war zone duck, a judge duck, a holiday duck—through the 1940s. In 1947, a fortuitous meeting of UO athletic director Leo Harris and Walt Disney resulted in a handshake agreement allowing the University to continue basing its mascot on Donald.

That same year, the Duck made its first appearance at Hayward Field (what’s left of the costume is on display at the Casanova Center’s Hall of Fame). Time may have robbed its feathers of their original sheen, but even so this ugly duckling had a frumpy, non-Donald look, with spindly legs, straggly yellow yarn hair, a pale beak, and limp faux feathers. In contrast, the image appearing on pennants and T-shirts was far more sprightly—a ticked-off Donald emerging from a stylized “O,” waving his arms in a show of Duck pique.

The early ’70s marked a time of political upheaval throughout the country and on the University campus, where student demonstrations became as much a harbinger of spring as hatchlings bobbing on the Mill Race. The Duck faced its own roiling waters. Following Walt Disney’s death in 1966, the Disney Corporation couldn’t locate a formal contract granting the University use of Donald’s image. In 1972, the corporation threatened legal action. The athletic department appealed to then UO archivist Keith Richard, who unearthed the storied 1947 photograph of Harris with Disney, who is sporting a UO jacket bearing the Donald logo, as proof of the informal agreement.

“Disney accepted it,” Richard says, and in 1973 the two parties signed a written contract.

For a while, everything was just ducky for the Duck. Then, beginning in 1979, Disney Corporation wrote a series of letters challenging the use of the Donald Duck logo and advising the University to “sell out all Duck-decorated items,” says Jim Williams ’68, then manager of the UO Book Store. But because the letters were addressed to the administration and not to the bookstore, which was independent from the University, Williams chose to let the matter slide. Like water off a duck’s back, you could say. For almost a decade.

“To me, it was a failure of understanding at Disney regarding the importance of the Duck to students, faculty, staff, alumni, and friends of the University,” he says. Since the letters weren’t sent to the bookstore, “we just kept on going.”

A 1982 letter informed the University that all items with the Duck logo would need to be ordered through the company’s special products division, a move that would have limited the bookstore’s product selection. Again, Williams stalled.

Williams again stalled Disney while he consulted copyright experts. Finally, in March 1989, Williams and the University’s athletic director, Bill Byrne, met with a Disney executive. They struck a deal that allowed the University to keep selling items with the Duck logo from its own suppliers, but stipulated the vendors pay Disney royalties, a deal that pretty much still stands.

While the Duck image was ducking legal hassles, the Duck mascot tried to keep from becoming lame. For some hard-charging coaches, the Duck just wasn’t tough enough. Jerry Frei, Oregon’s football coach from 1967 to 1971, wanted a toothier Duck to represent his “Fighting Ducks.” Dick Harter, men’s basketball coach from 1971 to 1978, wouldn’t acknowledge the Duck, and insisted all public relations materials refer to his players as the “Kamikaze Kids.” In 1978, an Oregon Daily Emerald graphic artist created a duck of different feathers, Mallard [accent on the second syllable] Drake, fashioned to be hipper and cooler than the incumbent. Loyal fans nixed the newcomer in a landslide vote—1,068 to 590.

Unflappable, the Duck didn’t even blink when, in 2002 during a University of Southern California football game, a buff, tight-rumped, possible usurper dubbed RoboDuck hatched out of a giant egg-shaped structure and began doing back flips down the field. “He’s not the evil twin. He’s the more aggressive, strong, obviously more flexible Duck,” explained a spokesperson. The Nike-inspired Robo was intended to complement, not compete with the Duck, but fans weren’t having any of him, and within months he was, yes, a dead duck. His demise doesn’t surprise Lynn Kahle, Ehrman V. Giustina Professor of Marketing at the UO’s Lundquist College of Business.

“Usually with branding, you need one representation of it. You can’t have multiple or competing representations of the brand,” Kahle says. “The image of Robo and image of the Duck we all know and love didn’t match very well.”

Since then, the Duck has gone his way unchallenged and mostly unencumbered. Disney kept the Duck on a short leash, limiting its appearances to athletic events or other occasions that had been cleared by corporate higher-ups. But the Duck, a plucky sort, disdains restraint. So, yes, there was the Shasta spat. And two years later an unauthorized appearance in “I Love My Ducks,” the wildly popular music video by a trio of UO students calling themselves Supwitchugirl, raised the hackles of some in University administration who feared the incident might foul the relationship with Disney.

But in 2010, Disney announced that the Duck and Donald were no longer birds of the same feather, thereby setting the Duck free to be bound only by University rules. Today, the Duck basks in the limelight, leading the roar of the crowd at Autzen, Matt Arena, and on the road. The Duck charges around the football field on a Harley, pumps the requisite pushups after scores, high-fives little kids, and charms fans with his winning waddle.

The Duck declined to be interviewed for this story, writing via e-mail that “the secret to our success is our anonymity. Once that’s gone our reputation and image is changed.”

Fair enough. Sometimes its better not to mess with a myth. What can be known is this: During games, the Duck’s internal temperature is twenty to thirty degrees hotter than what nearby fans are experiencing. The Duck drinks a lot of water, sweats buckets, and takes two five-minute breaks every hour. The Duck has a handler. A member of the cheerleading squad, the Duck goes to practices, works out in the weight room, and is eligible for scholarships. Each spring, hopeful candidates compete for the honor of being the Duck. It’s no small gig. Wannabe Ducks have to show they can maintain the essence of the Duck, because although many may don the Duck beak, the Duck is always one. And do not make the mistake of assuming the person animating the Duck is a particular gender or age.

“The Duck is continually growing, maturing. Through all life experiences, he changes,” says Robertson. Above all, the Duck must be larger than life, she says. “It needs to be the type of person that can come across big.”

—By Alice Tallmadge

Alice Tallmadge is a freelance writer and adjunct instructor in the UO School of Journalism and Communication.