ARRIVAL

On Sundays you had to come in early because of the balloon arch. The head hostess explains this as she shifts her ballast of wild-rye hair from one shoulder to the other by tipping her upper body at the hips like a metronome. She hates the balloon arch. Everyone does. That was why the responsibility fell to new hires. I could expect this shift for a while. She blinks to reveal eyes heavily lidded with blue eye shadow the same color as her irises, and walks me to the back of the house, where the helium tank and the bulging bag of limp balloons sit in a grimy corner.

But Sunday morning will be my favorite shift, at least at first. These early hours are unsullied. I am fresh like the dawn sky, lovely and unsuspecting in pink lipstick. The whole day’s adventure lies ahead.

It should be embarrassing, how much I love this job. I am a college graduate. I am supposed to be perched on the first rung of the career ladder. I tried to get a real job when I first moved to Portland from Eugene after graduating from the University of Oregon. I discovered all my psychology degree qualified me for was the graveyard shift at a home for deviant girls, pay rate $7.75 an hour. The prospect was so depressing I couldn’t even stomach an application. Instead I took a position as a hostess at a chain restaurant in a mall in Tigard. Here, I feel pretty and productive for the first time in forever.

“Like this,” Barb says, looping the arch’s primary string around a balloon stem. “Alternate colors.” Red, white, red, white: the balloons cinch together into a ten-foot centipede that twists determinedly toward the ceiling until we secure its ends to the brass rails on either side of the staircase that leads to the bar.

At night, the balloon arch is gone and this bar central. Luminous with bottles of booze against a mirror, it is the restaurant’s beating heart. There I perch nightly, drinking margaritas, conscious of how my legs lay tucked under my short skirt. I smile coyly and cross and uncross my ankles even if no one is looking, but someone always is. When you are twenty-three and new to the city, sex hovers around you like the endlessness of possibility.

* * *

Portland is the obvious destination for every small-town Oregon kid. The biggest city in the state beckons from afar, shining opaque brilliance from its northwest corner like the rays of the sun. Portland offers everything we think we’ve been denied: opportunity, culture, excitement. Surely life would be better there. Greatness must come easy in the city. Even if you don’t know why, you think you should move to Portland. Even if you don’t think it will stick, you’ve got to try it once.

* * *

New Year’s Eve. A trip over the Marquam Bridge, Portland lights humming below. Dom Perignon and a house crammed with taffeta and ties. We smile, we greet, we accept bubbling crystal flutes. We squeeze through tight passageways of shoulders and hips, fingers skimming each in invitation. We dance. Confetti falls. We laugh and laugh, tumble outdoors under a secret midnight and stars blurry and bright. We are young, we are beautiful, our tomorrows spill out before us, a red carpet of plenty.

* * *

The restaurant waits, quiet. The air hums with eagerness. Part of the thrill is never knowing what you are going to get. And then—bam, the place fills in twenty minutes, hostesses sent scurrying, bartenders flinging bottles, kitchen heating to a fast-paced burn. Waiting tables is all about energy: exuding, absorbing, radiating. Great reserves of energy invested, harvested, flung about. Each night, it could go two ways—spectacularly or disastrously. We could spill out the other end victorious, or things could slide slowly but surely toward chaos. Either way, the evening ends, is debriefed, is celebrated or mourned the exact same way—at the bar, together.

But in the beginning, it’s loaded with possibility. The air crackles with power and hunger, it licks at my toes like fire.

* * *

He slides into the bar stool next to me, saying nothing. Lights a cigarette, orders a beer, takes a sip and only then tips his eyes to me, offering that smile: part sex, part danger. “Hey,” he says. “Hey,” I say. A flame ignites in my gut. A couple of hours later, he pulls me toward him in my car.

DESCENT

I bent over the jagged line of cocaine and stuck a rolled dollar bill up my nose. The white powder had been chopped on a Nine Inch Nails CD case that I would lick clean later, scraped with a credit card into a neat, narrow pile. By now, I’d stopped arguing with myself. The money was spent, the powder mine, the electric rush to the head on its way, and regret staved off until morning.

It would come, I knew. From this vantage point, crouched unceremoniously over someone’s crappy kitchen table, surrounded by men, about to relinquish myself to the dark embrace of night once more, tomorrow’s remorseful agenda was fixed. The bright morning hours of yet another glorious summer day would be spent either sleeping or in wretched, salty-eyed agony. The better part of the afternoon would creep forward in a cloud of self-hatred. The evening would pass in an internal war already doomed to failure. And after dark, this. The inevitable caving-in. I never went outside anymore. I had no idea where I was. I could have been anywhere.

The drug was quick. Instantly, I felt the stinging in the back of my sinuses and then the rush to my blood. My whole body tingled, lifted, and—blast off. We talked and talked—for hours, we talked. There was so much to say, and we were so fascinating.

I would sleep with him, too, of course. This as well was inevitable. He and the drugs were the same. The first time had been a cheap thrill. The second time to test the first. The third, habit. Just like that, and nothing better to do anyway. From then on, sex and drugs swirled together into an irresistible tornado whipped up nightly just for me.

Every night on toward dawn I’d close myself into the bathroom of whoever’s cheap apartment and stare at myself in the mirror. Only the face didn’t look like mine. This girl was prettier than me. Bold, daring, full of something strong and wild. She could take on anything, except for that she wasn’t real.

* * *

Walk until you feel better, I told myself later, when I was in deep enough to know I needed rescuing but saw no one to do the job but me. I parked in Johns Landing and set forth on the riverfront trail. I was afraid to venture out of town, into the unfamiliar wild, even though by now I knew that nothing in this city would ever satiate me. I yearned for my small coastal hometown, or maybe just anything that felt like home.

At first, I could find myself if I walked for an hour. As the Portland summer wore on, it took longer. As I slept more of the day away, I had to hurry to fit in the walk before my night shift. But I would, because I had to. With no walk, I began the long night’s sure descent without an ounce of my soul along for the ride.

* * *

We hurtled down Interstate 5 in my tiny Honda, Mark driving. Our regular dealer was sold out; he knew someone in Woodburn who could hook us up. It was much too late. We should have just gone home to bed. But the demon calls.

Mostly, I kept the danger we taunted nightly at bay. But speeding south of Portland in that small car, all of us drunk and high, the highway abandoned, the empty fields dark on either side, I was thrown out of sorts. I recalled suddenly that my grandmother learned to drive on this road. In the 1920s, before it was a highway, her three older brothers brought her from their Portland home way out here because it was nowhere—the perfect place to teach one’s sister to drive.

I imagined the four of them in newsboy hats and tweed, laughing and lurching down a country road, maybe in this same exact location, intent with camaraderie and purpose. I looked at the four of us. We were not laughing. We were not wearing tweed. We had no purpose.

* * *

Desperation finally trumped fear. Worse things could happen than going forth into the wilderness in my sister’s unreliable car, getting lost, being caught on a wooded trail alone, tripping, falling, dying.

One Monday morning, I studied a map of the state of Oregon at my little card table. I circled the scribbled line of a trail along the Columbia Gorge, charted the highways to get there. My heart thumped with risk and hope.

* * *

He was sleeping with the new hostess. In under a year I’d become old news, the girlfriend used up, the novelty replaced by a girl of eighteen with breasts like melons.

I kept having sex with him anyway.

* * *

In a month’s time I hiked the Coast Range, Tryon Creek State Park, the Columbia Gorge. Always alone, always nervous about setting forth into the unknown. But I didn’t care anymore.

Once in July I waded into the middle of Silver Creek in Silver Falls State Park and sat down in the current. Icy-cold water ran around my waist, soaked my shorts and T-shirt, pushed over my toes, still in their shoes. I felt nothing.

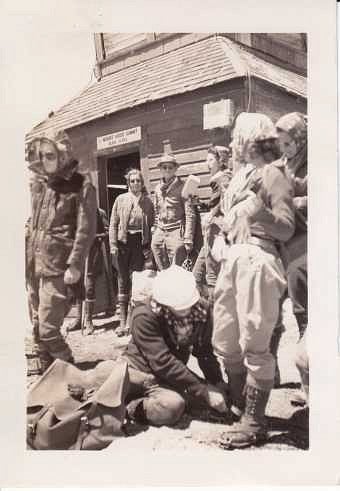

I dreamt about my grandmother. She climbed Mount Hood in 1938. I could see her. She was shrouded in wool. She wore big leather boots with corded laces and followed a line of people straight up a snowy field toward the sky. I stood far below her, near the board-and-batten expanse of Timberline Lodge. I wore modern street clothes. We were separated—between us distance and time, the wooziness of a dream, her calm strength, my reckless weakness. But she turned back to face me for a moment, shoving an old ice axe into crusty snow and cocking a knee to root herself. I could barely see her face. She may have been smiling. Come along now, she beckoned.

* * *

The night I found myself wandering alone at three a.m. on the waterfront, just north of the Portland Athletic Club, too high to sleep with nowhere to go under the dark of no moon, I was finally jolted from my stasis. He had come to my apartment and gone, the briefest encounter, sex without intimacy just like always, and yet this time enough to leave me wide awake and devastated. The loneliness was so horrible that it drove me out into the street.

On the arc of green grass over the harbor, where in the day’s bright sun children danced to the music of summer concerts, it hit me. I stumbled over a hump in the grass, nearly fell, jerked upright, felt the shock of exactly where I was.

You are in danger. You graduated sixth in your high school class. You have a family who loves you. You are not to end up a headline. This is not your life, and it sure as hell isn’t going to be your death.

I ran back to my car, panting, and locked all the doors.

DEPARTURE

Where do you start looking for you when you’ve lost you altogether? First, you call your dad. Then you get some sleep. Then you leave everything behind and go searching once more. The answer turns out that you are nowhere, and everywhere. You are right here and have been all along, trying to find your way home.

You travel about and collect pieces of yourself and tuck them in your pockets, hoarding and savoring until they become whole.

—By Kim Cooper Findling

Kim Cooper Findling ’93 grew up on the Oregon Coast and now lives in Bend with her husband and two daughters. Her work has appeared in many publications over the past decade, including Travel Oregon, Horizon Air, Oregon Quarterly, Runner’s World, Hip Mama, Sky West, The Best Places to Kiss in the Northwest, and High Desert Journal. She is the author of Day Trips From Portland, Oregon: Getaway Ideas for the Local Traveler, published by Globe Pequot Press in May, and Chance of Sun: An Oregon Memoir, to be published by Nestucca Spit Press in August.