For many backwoods hikers the trek is an opportunity not only to experience the challenges of the trail underfoot but also to explore the terrain of the psyche. In Cascade Summer: My Adventure on Oregon’s Pacific Crest Trail (AO Creative, 2012), Bob Welch ’76 details his self-propelled journey from California to Washington. The book, excerpted here, is the thirteenth for Welch, a columnist at the Eugene Register-Guard who has served as an adjunct professor in the UO School of Journalism and Communication.

Date: Thursday, July 28, 2011. Days on the trail: 6. Location this morning: Deer Lake, 12 miles northeast of Oregon’s Mount McLaughlin. Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) mile marker: 1,801.4. Elevation: 6,150 feet. Miles hiked Tuesday: 23. Wednesday: 13.2. Total miles hiked: 98.2. Average per day: 16.4. Portion of 452-mile trip completed: 17.8 percent.

This was it. Shortly after the 4:50 a.m. wakeup beep from my Casio, I lay in the darkness and thought: By day’s end [hiking companion] Glenn and I will either be past Devils Peak or heading home, our trip in shambles. In 8.6 miles, we would know our fate. I prayed a prayer for wisdom, courage, and strength, then slid on my headlight and reached for my still-damp clothes that hadn’t been washed in nearly a week. Show time.

Each year, particularly in California, snow spoiled hikers’ Pacific Crest Trail dreams. Sometimes it only delayed those dreams. People with flexible time schedules might hop ahead to a lower-elevation section, then return at trip’s end, after significant snowmelt, to finish what they’d missed earlier. We had no such flexibility. No, this was it. By this afternoon, it would be either on to Crater Lake for a triumphant reunion Saturday with our families—and fresh supplies—or a marathon-distance trudge back to Highway 140, knowing we’d failed.

It was a quiet walk, the only revelry being muted recognition that we had hit the hundred-mile mark of our journey. I took my mind off Devils Peak—and its prelude, the equally sinister-named Lucifer—by thinking of Judge John Breckenridge Waldo. In September 1888, he had come south near where the PCT was now, camping at Island Lake, which we now passed a quarter-mile to the east. Today, this area was known as the Sky Lakes Wilderness Area.

Waldo spent most of his summers in the 110-mile stretch between Mount Jefferson and Diamond Lake. But in 1888, at age forty-three, he and four others ventured this way on a trail far cruder than the well-maintained PCT we now followed.

Waldo was Oregon’s John Muir, the naturalist who founded the Sierra Club, and whose mountain journeys, too, once took him north through this area, to

Crater Lake. For Waldo, the high-mountain experience was religion without church. “Here I am at Pamelia Lake, breathing the pine-scented air and already feeling much stronger, both in body and spirit,” he wrote in 1907. “Blessed be the mountains and the free and untenanted wilderness.”

* * *

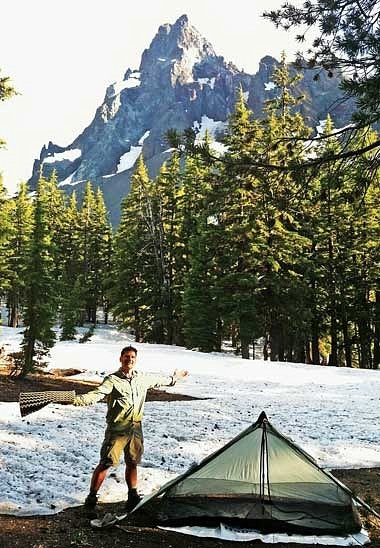

About three miles from Devils Peak, patches of snow started dotting the trail, the first on-trail white that we had seen since the day we left the Oregon-California border. We had ascended about 500 feet since leaving Deer Lake about three hours before.

The snow patches rose and fell as if the backs of albino whales breaking the ocean’s surface: perhaps two to five feet high, gradually sloping up and down. Each foray over snow widened my imagination to the possibilities of what lay ahead—possibilities iced with a certain foreboding. At one point, we stopped to look at our maps. The tightly spun brown-on-white contours etched a four-point challenge: Luther Mountain, Shale Butte, Lucifer, and, finally, Devils Peak. Glenn was the one who’d studied the maps in detail; I had never imagined the trail chiseled this high into the ragged flanks of mountains.

Since news of the dangers at Devils Peak, we’d shared our thoughts with each other, briefly, on a few occasions. Both of us wanted to get to the Columbia River; neither one of us was willing to put our lives on the line to make it happen. We had too much for us back home in the way of family and friends. What I hoped for, then, was a clear sense that we were safe to proceed or foolhardy to do so. Black or white. Head on or turn back.

As we rose higher, to the timberline, Mount McLaughlin rose majestically behind us, its north face far whiter than the south face we’d seen while crossing Brown Mountain’s diabolical lava fields. Devils Peak’s north face, I was reminded, would be similarly chalked in white.

We moved on. I took the lead. Wildflowers fronted jagged shale, a reminder of the Cascades’ beauty-and-the-beast nature. Glenn stopped to take some pictures, particularly of feathery flowers that seemed to defy the rugged land and lofty elevation. (In his journal, Waldo mentioned taking pictures, too. In 1888, George Eastman had introduced the Kodak, a square box camera using roll film, and photography had become a practical hobby for Americans overnight.)

At 7,000 feet, on the west flank of Luther Mountain, we reached our highest point since the trip started. What impressed me, besides a sprinkling of red, purple, and yellow wildflowers, was the sheer bigness of the land beyond: Massive mountains splashed with sheer walls of shale, craggy peaks here and there, rolling buttes of timber speckled with white-bleached snags that may have watched silently as the Waldo party had jostled down the spine in 1888. Geographic features that we’d never heard of and were small potatoes compared to, say, Mount Jefferson or Hood or the Three Sisters, and yet scattered 360 degrees around us in a display so large as to humble me, a mere ant amid God’s sprawling grandeur. About 3.7 percent of Oregon was designated “wilderness,” another 8 percent publicly owned forests wild and unprotected. But from this perch it seemed the whole world was untamed wilds.

* * *

“Mornin.’”

I mentally lurched. The guy seemed to have materialized as if beamed here from a Star Trek teleportation machine. He was up a slight hill to my right, amid a clump of trees, in front of two tents. Like me, he looked late fifty-ish. He had what appeared to be a cup of coffee in his right hand and seemed no less casual than if he’d been my neighbor standing on his porch and seen me going to fetch the morning paper.

“Hello,” I said.

“Acorn,” he said, extending a hand.

Huh? Oh, of course, his trail name. He was, I realized, a PCT hiker. We hadn’t seen many.

“Uh, I’m Bob,” I said. “That’s my brother-in-law, Glenn, back there. You thru-hiking?”

“Doing a section with my daughter, Ashland to Crater Lake,” he said. “Got turned back by Devils Peak. Too tough. Too much snow. So far, four have made it past. Four have turned around.”

[Editor’s note: For those wondering, Welch completed the hike.]