On a warm July afternoon, Willie Taggart sits in his new office at the University of Oregon, smiling back at the memories from his days growing up in Palmetto, Florida. The memories are as fresh as if the games that produced them took place days ago, rather than decades. Maybe they’re so vivid because they have to do with something Taggart loved as a kid: playing football with his neighborhood buddies.

Willie and his friends played pickup football after school. No coaches, no parents, only fun. Sometimes, they improvised with a game called “Throw ’em Up, Bust ’em Up.” The football got tossed, and whoever grabbed it had eight guys to outmaneuver to the end zone. No blockers, no rules, just hard hits and long laughs.

As they got older, they all wanted to take their game to powerful Manatee High School, including Taggart. He was a wispy 145 pounds—“as thin as the wind” was how some in Palmetto described him. But size didn’t keep Taggart from going after the prized job on the field—quarterback—or putting the lessons of “Throw ’em Up, Bust ’em Up” to good use.

One play crystalized Taggart’s tenacity. It came in his first-ever start as a high school quarterback on a fall night in 1991. After taking the snap from center, Taggart broke tackles. The goal line was in view, so he raced toward it . . . crossing it just as a defender collared him. As one teammate said later, “The guy threw Willie down like he was throwing a towel off his shoulder.” The hit didn’t faze Taggart—or at least he had learned not to show it. He bounced up and rushed to the sideline, where high-fives from teammates awaited him.

The years have passed, and Taggart, now 41 and the new head coach of the University of Oregon Ducks, is 3,000 miles from the fields he played on, the friends he collected, and the sometimes-unkind streets he walked. He’s stockier, and specks of gray dot his hair and beard. But one thing is very much like 1991: Taggart has people believing in him—believing that he can make Oregon football a national power again.

And why not? His résumé says he can turn programs around. He took down-and-out South Florida to bowl-eligible in three seasons. Before that, in 2010, he inherited a team at Western Kentucky University—his alma mater—with a 26-game losing streak, and guided the Hilltoppers to a winning record in two seasons.

His secret? From his office in the Hatfield-Dowlin Complex, Taggart overlooks the practice field. Rimming it, large and bold, is signage with the motto he’s brought to his team: Make No Excuses. Blame No One. Do Something. On this summer day, five weeks before the season’s start, Taggart points to the slogan. “Winning is not complicated, people are complicated,” he says. “If we don’t complicate things, we can win.”

Sounds easy, like “Throw ’em Up, Bust ’em Up.”

No doubt, Taggart has brought some southern style to the Pacific Northwest. He enjoys ribbing his players. When he saw his starting quarterback, Justin Herbert, talking to a reporter this past summer, he snuck up, grabbed his shoulder, and said, “Man, look at those guns!” It’s this amiability and enthusiasm that his players have come to expect. “That is Coach Willie,” says Royce Freeman, senior running back and team captain. “He and his staff bring his energy every day, and they expect the same out of us.” Taggart brings a similar good nature to his media briefings. While some coaches (see Belichick, Saban, Kelly) can make a press conference about as inviting as an organic chemistry exam, Taggart seems genuinely disappointed when one wraps up. “That’s it? It’s over?” he said when a preseason press meeting ended. “This is fun. Two more questions . . .”

Relocating to Eugene, Taggart brought more than a smile and joie de vivre. He packed the lessons of 941, shorthand for his hometown (it’s Palmetto’s area code). Sure, he grew up “playing football, football, football.” But life in the town south of Tampa wasn’t always the thrill of Friday night lights. He also talks about less dazzling days. About weekends picking oranges with his mom and dad, both sharecroppers, to make extra money for the family. About “Christmases when I didn’t get anything. I woke up and I didn’t have toys or bikes that other kids had. That was disappointing.” And he talks about buddies he played with, some who would go on to big-time college careers and “to play on Sundays,” and some who wouldn’t.

“There were a lot of drugs,” he says, “and a lot of my friends fell to it. I always count my blessings. I could easily have been like my friends.”

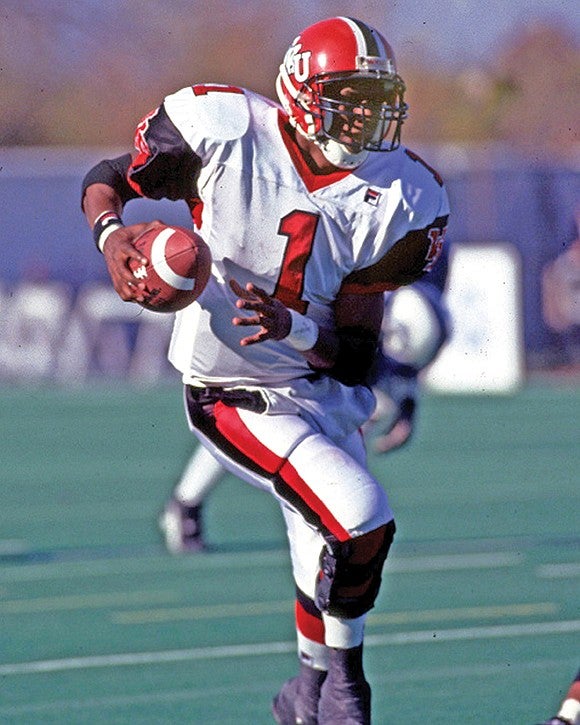

He got a boost when he was recruited to WKU in 1994 to play for Jack Harbaugh, father of Jim and John Harbaugh of NFL fame. He spent freshman year on the bench; as a Proposition 48 recruit, he lacked the minimum high school GPA to play. But over the course of his college career, Taggart helped revive a dormant football team, his bust-’em-up style impressing his coach. “[Jack Harbaugh] was excited by how I was playing and competing and taking hits,” says Taggart, a two-time finalist for the Walter Payton Award, given annually to the most outstanding offensive player in college football. “I had some bumps and bruises, but they couldn’t keep me out.”

A long-term relationship was sealed. After Taggart graduated but failed to latch on with an NFL team, he accepted a job on Jack Harbaugh’s staff that launched his coaching career.

Since taking over the Ducks, Taggart admits that there have been, well, more bumps and bruises, both professionally and personally. He dealt with turmoil brought on by coaches that he had hired (one of whom was later fired). He dismissed star receiver Darren Carrington for disciplinary reasons. And just three weeks before opening day, his father, John, died suddenly from cancer. The loss was immeasurable. A day hadn’t passed since Taggart’s arrival in Eugene that he hadn’t connected via a phone call or text with his parents. “My dad and mom are always together, so whenever I’m on the phone with her she will pass it to my dad,” he had said just weeks before his father’s death. “My mom and dad couldn’t tell me what college was like, but they taught me how to work.”

There is a focus to Taggart’s work today. When he left Palmetto in 1994 for college, his goals included becoming the first in his family to graduate college (check); finding a wife (check—he married Taneshia Crosson in 1998 and they have three children); and getting drafted by the NFL so that he could buy his parents a new house (unchecked). As he recalls this list, he smiles, saying, essentially, two out of three ain’t bad. Now, as a college coach, he simply wants to win a Division I national championship. For his best shot, he’s traveled 3,000 miles from home. He’s arrived loaded with lessons learned a long time ago, a long way away.

“I am always representing the 941 area code no matter where I’m at,” Taggart says. “Growing up there made me the person I am today. Working hard. Make no excuses for anything. It has always been something that is with me.”

—By Charles Butler

Charles Butler, an instructor in the School of Journalism and Communication, has written for the New York Times, Fortune, and Runner's World.