The first one-year earthquake hazard report issued by the U.S. Geological Survey need not stir panic for Oregonians — beyond our already frayed nerves about an impending Cascadia rupture.

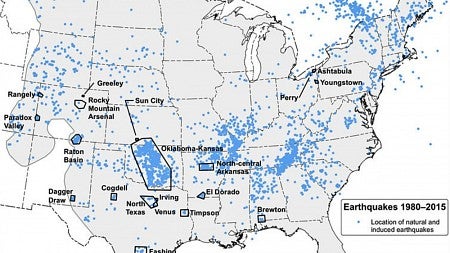

There are policy implications, says UO geologist Ray Weldon, a member of the report’s steering committee. The document, issued March 28, for the first time included induced earthquakes from the Great Plains to the East Coast.

Induced quakes have been thought to come from hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, but the process itself usually isn't a direct producer, the report noted. The process injects chemicals, sand or water into the ground to enhance oil and gas removal, but the effects are in a limited area. Induced quakes, Weldon said, are more likely when wastewater generated by fracking and related production is removed and injected at high rates and volume at other locations for disposal.

Industry officials and some politicians in states where fracking occurs resisted having induced seismic activity in the National Seismic Hazard Map published in 2014, Weldon said.

"This report is a compromise. We agreed to not include unnatural earthquakes in the national source model that goes into building codes," he said. "Instead we will produce an annual report that says what that hazard would be if they are included. Induced or not, in my opinion, an earthquake is an earthquake and we should be saying something about the frequency of earthquakes to the best of our ability."

RELATED LINKS

While there is no oil-and-gas fracking in Oregon, an energy company has been injecting water into the ground near the Newberry volcano to try to extract geothermal energy from the water's contact with hot rocks below the surface.

"The test sites at Newberry are in a very dry place, so there's little groundwater that is being naturally heated," said Emilie Hooft, assistant professor of geological sciences who was not involved in the USGS report but has extensively studied the Newberry volcano. "The idea is to pump water into the ground to try to make a permeable network where the water contacts the hot rocks."

The company monitors the seismic activity, which is expected and helps to assess if injections are working, she said. "These earthquakes are meant to range from a magnitude of -2 to 2," she said. "They've done two test pumps. In one case, they made a deep earthquake at magnitude 2.1. If they exceed the maximum target, they are to stop and let the water back out."

There are no federal guidelines for fracking, but the U.S. Department of Energy asked that the geothermal project follow international protocols. The work at Newberry meets those standards, Hooft said.

"There is legislation pending in some states to initiate controls for oil and energy companies to limit the rate and volume in an effort to limit the size of earthquakes," Weldon said. "In other parts of the world, induced earthquakes have reached up to magnitude 6."

Any liquid injected into bedrock can generate quakes, he said. In some experiments, liquidized carbon dioxide has been put underground. Parts of Oregon and Washington have been identified as having rock types that could store carbon dioxide, a key contributor to global warming.

Building codes, insurance rates and emergency-response planning are tied to the USGS hazard reports that are issued in six-year cycles, said Weldon, who has worked on long-range reports for California and Oregon.

The oil-and-gas industry argued that because they move production around, "earthquakes caused today won't be the earthquakes that are caused tomorrow," Weldon said.

However, he noted, induced earthquakes happen in clusters, as do natural ones. Once clusters are mapped for a region, algorithms smooth the data to determine an average hazard value. In Oregon, maps based on clusters will result in an equal hazard for places that have never had an earthquake.

"This new report," Weldon said, "gives the impression that, one, we know more than we know, and, two, it gives the impression that the statistical approaches that we take to generalize from the sparse and clustered earthquakes are somehow better understood on a yearly basis than it is on a longer-term basis. All hazard maps are completely based on smoothing algorithms that are intensely debated by seismologists and statisticians."

Oregon has about a 1 percent chance of a damaging quake this year, according to the report. Seismologists, meanwhile, project a 20-to-30 percent chance for a magnitude 9 Cascadia quake within 50 years; the last one was 316 years ago.

— By Jim Barlow, University Communications