The discovery reads like an action story: Archaeologist and Museum of Natural and Cultural History research affiliate Scott Williams and his crew had 90 minutes to get in and out of a treacherous cave on the Oregon coast.

The cave, blocked by hazardous rocks and crashing waves, hid a treasure: a long-lost ship mast. The crew hustled to recover the mast with water rescue equipment.

In June 2022, Williams worked with volunteer archaeologists, first responders and state officials to recover several large pieces of timber belonging to a shipwreck known as the Beeswax Wreck, one of the wrecks that inspired the film “The Goonies.” Easy to miss in the excitement was the decades of research preceding the day’s urgency.

For centuries, people living around Nehalem Bay have found signs of an ancient shipwreck. Nehalem-Tillamook and Clatsop tribal oral histories tell of a ship crashing off the Nehalem Spit. In 1804-05, the Lewis and Clark expedition traded with the Clatsop for beeswax blocks from East Asia and met people they described as descendants of shipwreck survivors.

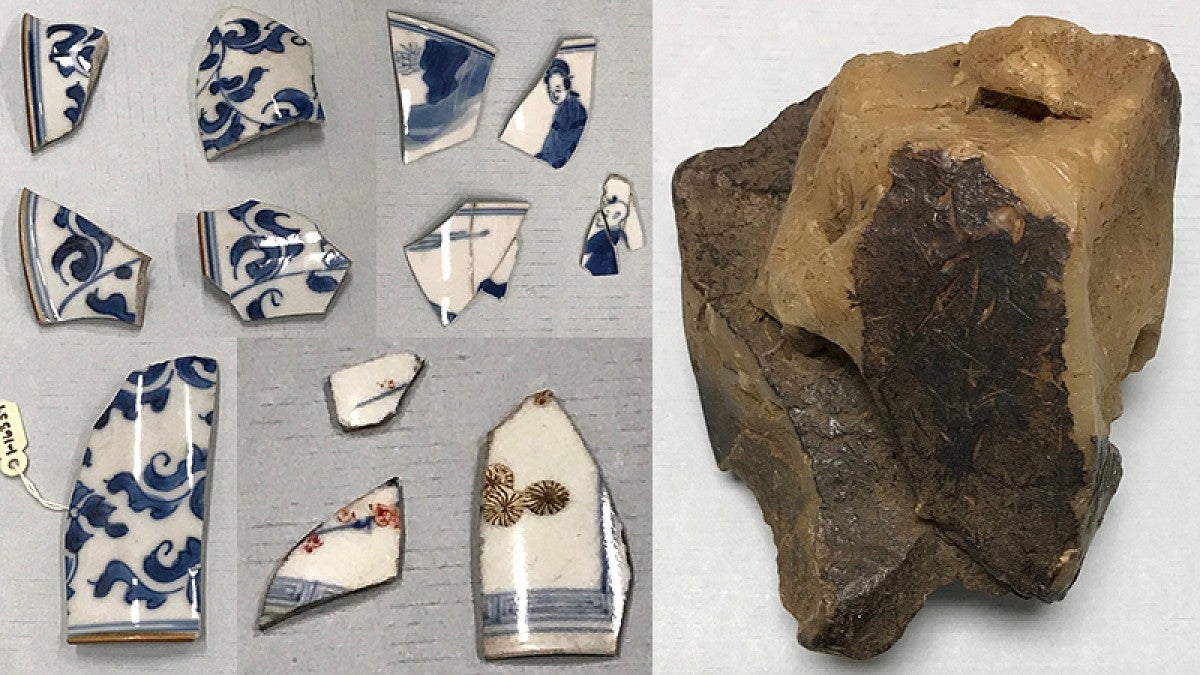

Generations of beachcombers, from Indigenous residents to travelers today, have found chunks of beeswax, fragments of Chinese porcelains, and other European artifacts scattered along the bay’s eroding shorelines. Several of these artifacts now reside in the UO museum’s collection vaults.

Beginning in the mid-1900s, Oregon researchers began to piece together the ship’s history. In a 1981 museum bulletin, Oregon anthropologists studied the patterns on Chinese porcelains to postulate a broad 17th-century age range for the wreck.

The mystery came to museum director Jon Erlandson’s attention in the late 1990s, when a student mentioned an old Spanish-style rigging block found by a beachcomber housed at the Columbia Maritime History Museum. Erlandson arranged for high-precision radiocarbon dating of a small wood shaving from the block, which suggested that it dated to the mid-17th century. The analysis narrowed the time frame for the ship’s demise.

Williams picked the project back up again in the early 2000s and has worked with his team of volunteers ever since to learn more about the ship and locate the wreck site. His work yielded results, and today we know that more than a century before Lewis and Clark arrived in Astoria, a Spanish “Manila galleon” wrecked off Nehalem Bay. The ship carried beeswax for candles, Chinese porcelains and other goods from the Philippines to the Spanish port of Acapulco in New Spain, what is now Mexico.

Fast forward to 2022. The June cave find was the first recovery of large timbers and masts from the shipwreck. Erlandson and the museum got involved again, this time funding Williams’ radiocarbon dating of the newly found timbers through the museum’s new Center for Archaeological and Interdisciplinary Research and Education. The dating confirmed the timbers were the same age as the previously found rigging block, tying the two finds together and finally linking the Beeswax Wreck to a Manila galleon that went missing in 1693, the Santo Cristo de Burgos.

This marks the earliest documented contact between Europeans and the Indigenous tribes of the Pacific Northwest coast. In “The Beeswax Wreck of Nehalem,” published in the Oregon Historical Society in 2018, Williams and his colleagues posit that potential survivors “might have interacted with and integrated with the Native American communities they would have encountered once they made it to shore.”

“This is one of the great stories of Oregon history,” Erlandson said. “Before Captain Cook and Lewis and Clark, there were undocumented contacts between Native Oregonians and Europeans that only archaeology and Native oral histories can document. The MNCH and CAIRE are proud to support the remarkable work of Scott Williams and his colleagues.”

Williams continues searching for more insights into the ship, the cause of the wreck, and the interactions of the survivors with Oregon coast Indigenous communities.

—By Becky Raines, Museum of Natural and Cultural History