A UO professor will join researchers from around the globe in an effort to better understand the ice loss happening across Greenland as well as the social issues Greenlanders are facing as a result.

A National Science Foundation award of $2.9 million will fund the collaborative effort in Greenland over the course of five years. The project includes UO professor Mark Carey, director of the Environmental Studies Program and the UO Glacier Lab, and is led by Fiamma Straneo at Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

The ice sheet across Greenland feeds into fjords, long narrow inlets that connect glacier-covered land to the surrounding ocean. The water and sediments from the annual ice melt create nutrient-rich water in the fjords, which then sustains marine mammals, fish and seabirds. Those often are used by native Greenlanders, who rely on them as resources.

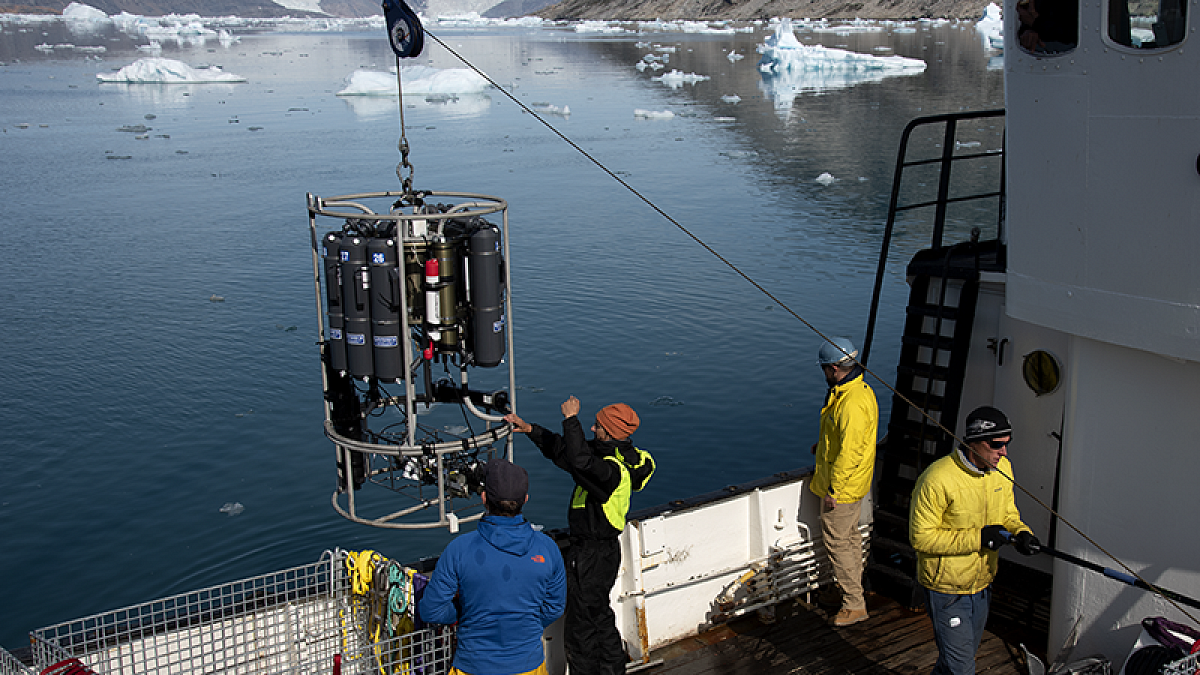

Now as a result of climate change, the Greenland ice sheet is shrinking and the melt rates are accelerating. The shift is altering not only the temperature of the surrounding waters but also the entire circulation of ocean water coming in and out of the fjords, as Dave Sutherland, a UO professor of earth sciences and environmental studies, has investigated for years through his Oceans & Ice Lab.

The goal of Carey's new research project is to better understand the processes that are sustaining those ecosystems while working in tandem with researchers in Greenland. The research will aid in development of adaptive and sustainable strategies to counter a rapidly shifting climate.

“We are looking to the expertise and local knowledge of our Greenland partners throughout the entirety of this project, with the final outcomes coming from the communities themselves and what works best for them,” Carey said. “Our team is helping to add pieces to the puzzle. We are learning how global forces are impacting people at the ground level, which could be helpful not just for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, which we desperately need to slow sea level rise and melting glaciers, but also for U.S. relations with Greenland that spans from tourism and fish consumption to offshore oil development.”

What sets the study apart is being a multidisciplinary project that includes the human impact, Carey said. The team will not only be looking at the biological and geophysical dimensions of the surrounding ocean but will also focus on human societies as well, with the Indigenous communities around Greenland a central part of the story.

“Often you hear the story of climate change, but you miss the human aspect,” Carey said. “Take for example Greenland in the 1950s. If we just look at climate, we see climate variability already happening, but that’s also when the U.S. military began building military bases there and forcibly relocated one of the Greenlandic communities in order to make room. This is climate change and political policy intersecting, and that’s something we’re really interested in learning more about.”

As the effects of climate change continue to alter how societies interact with the environment, policies and regulations adapt at the same time. Carey’s team will look at factors like fishing regulations, market fluctuations and fish prices as part of the project.

Carey said a transition toward increased halibut fishing has occurred over recent decades, and changes in fishing practices based directly on climate change is one thing the team will continue to research and measure.

The political relationship with Greenland’s own autonomy and the historical shifts of power are another factor Carey said the team look at as it develops its research. That holistic, community approach to research builds stronger connections to the Greenland partners and provides funds for Greenlanders to be partners with the external team, and Carey said that’s what really sets this research opportunity apart.

—By Victoria Sanchez, College of Arts and Sciences