In the fall of 1977, along with the incoming class, the University of Oregon welcomed another group of fresh faces.

More than 100 Hollywood professionals—actors and gaffers, makeup artists, camera crews—arrived on campus to shoot a low-budget movie. The director was unestablished and the cast consisted mostly of young unknowns. Universal Studios allotted just $2.8 million for the picture and they wanted it made quickly.

The studio’s expectations for National Lampoon’s Animal House may have been modest, but for UO students, faculty, and staff, spending the fall term elbow-to-elbow with a Hollywood production proved to be a major event.

“At that time, we had no idea what the storyline of the movie was going to be about,” recalls David Boone, an Oregon native who was beginning his sophomore year. “All we had heard was that it was going to be set in the early 1960s. This was ’77 and we all had relatively long hair. Everybody suddenly went out and got haircuts or they tried to dress up in a period style, because people wanted to be cast in the movie. Almost overnight, the whole campus took on this retro theme.”

Boone reflects, “I was with two other guys, walking through the middle of campus, a beautiful fall morning when the leaves were turning. Suddenly, I look over at Johnson Hall and there’s people pulling a white horse into the building! We all were laughing and going, ‘What the hell?’”

The entire shoot lasted for 32 hectic days and then, as suddenly as they’d arrived, the actors and filmmakers departed for Los Angeles and New York. Afterward, the UO and Eugene would never be the same. In fact, no college town in America would ever be the same.

It was more than a hit—the rude and raunchy, low-budget comedy became a cultural event. Critics were lukewarm, but audiences ate it up. After its opening on July 28, 1978, Animal House would earn more than $140 million at the box office, becoming one of the most profitable films of all time.

For Oregon, the movie has a complicated history as both cinematic milestone and reputational millstone. Understandably, it’s a little awkward as an institution of higher learning to be so closely tied to a movie that taught the world how to toga party and destroy a homecoming parade. The university initially tried to hide its participation in Animal House—President William Beaty Boyd had only permitted the producers to shoot on campus on the condition that the UO would not be mentioned anywhere in the film—but our buildings and landmarks were captured in Technicolor and unmistakably projected onto the silver screen.

“Over the years, as the film endured and grew in local legend it also became an acknowledged part of Oregon culture and the brand of the university,” notes Michael Aronson, head of the Department of Cinema Studies. “Movie locations get pointed out on campus tours and everyone sings ‘Shout’ at the football game along to the toga party homage advertisement produced by a certain popular shoe company.”

Today, picture a cake with 40 candles stuck on top and a frosting flourish that spells out “Eat Me.” While Animal House is having a birthday, the big four-oh can be a mixed bag. And comedy has a reputation for aging less gracefully than other genres.

“The problem is the film is bad, really bad,” says Aronson. “It might be fondly remembered if you haven’t watched it in 30 years, but Animal House is awful; wildly misogynist, homophobic, and racist.”

I hadn’t viewed it in a long time, so I took up the professor’s challenge. Revisiting the film from a more (ahem) mature perspective, I was surprised by the unremittent raunchiness of its humor and its more-than-occasional mean-spiritedness. Admittedly, I still found things to laugh at. On the other hand, there was more than one scene where it was really hard not to cringe.

There are moments when watching Animal House will probably make you cringe, too. When the movie invites the audience to laugh along as a protagonist struggles with his libidinous urges in the presence of an intoxicated, unconscious girl, to name one example. Or when it mines uncomfortable humor from racist stereotypes in the scene at the Dexter Lake Club. (The Black extras had to be bused in from Portland.) Given today’s cost of a college education, it even feels a little unsavory to chuckle over Delta House’s sub-1.0 GPA.

“The film does not represent what fraternities were founded on or what our organizations are truly about,” says Caitlin Roberts, UO’s director of fraternity and sorority life. “However, it’s had a big impact on those who watch and are not familiar with fraternity life. Over the years, we’ve had many conversations with parents who are very concerned that Animal House is what their children are joining. Given the media attention that fraternities and sororities nationwide are receiving now over some very critical issues, there really isn’t a lot to laugh at.”

However it looks today, this much also is true: in 1977, the film’s creators believed it was guided by a spirit both liberal and liberating. Its ethos was antiauthoritarian, its humor a well-deserved raspberry aimed at the smug privilege of respectable, middle-class values. The screenwriters conceived of the film as an escapist glimpse back to their own, carefree college days—in their estimation, the last era of “American innocence” before Vietnam and the political turmoil of the ’60s.

But this is a perspective of yesteryear, framed by the lived experiences of baby boomers. Today’s more immediate and relevant issues for college-aged people include Title IX, #MeToo, and intense debates surrounding social inclusion and free expression. What’s more, we now live in a fractured media landscape with exponentially increased entertainment options, and notions of “canonical works” in any given genre are coming to be regarded as passé.

“Ten years ago they were more aware of it,” Roberts reflects. “But when we ask today’s students about Animal House, their response most often is, ‘What’s that?’ Their references for college life are all newer movies and shows.”

Unlike many of his peers, first-year journalism and political science major Zack Demars saw Animal House a couple times before coming to college. “Each time was more painful,” he says. “It’s a classic University of Oregon movie, and it’s funny in its own kind of very crass and crude way. But if you watch with any sort of a critical lens, it’s obvious that it was a movie of its day, and the day has changed.”

After a recent screening in Kalapuya Ilihi residence hall, Demars and other students in the audience noted that the movie’s point-of-view always treats nonwhite people as “The Other.” They were turned off by protagonists who use terms like “homo” and “retard” as putdowns. They felt that too many of the jokes objectified women, glorified harmful behavior, or betrayed implicitly racist attitudes.

“The writers are so creative, they should be able to come up with something that will make me laugh without implying that a girl is going to be molested,” says history major Isa Ramos. “I would hope to think that we as a society have decided that certain things in that film are unacceptable.”

However, this student audience’s final review of Animal House was tepid at best. They thought the plot was overstuffed and unstructured, and too much of the dialogue hinged on insults. They were critical of the gratuitous nudity.

More than one viewer described the film as “old fashioned”—an ominous sign with regards to any media artifact’s prospects for longevity. More ominous still, “overrated.” And finally, the judgment that is most gravely portentous for anything intended to be timeless comedy: “Not all that funny.”

In conclusion, what are we Ducks to make of our entwined history with Animal House, now four decades deep?

“Even if some of the humor is not anything that I would endorse, it’s still pretty cool that it was filmed on campus,” Demars says. “That the popular culture of the time was taking place here is still something that people are excited about.”

Ramos adds, “Parts of the movie even look beautiful, if you can ignore the context.”

The aforementioned Boone, whose son Duncan attends the UO, notes, “I’ve watched it with him. He’s a disciplined kid. He likes to party at the right time and do fun things, but he knows when to buckle down. I did too, frankly, back when I was in college. In addition to having fun, we all have a responsibility to be ethical people. You have to take Animal House in the right context.”

Context. It’s always critical. A number of the film’s principal creators are now deceased and can provide us with none. In its own defense, the movie offers only a classroom lecture positing that Satan is the most interesting character in Paradise Lost, plus the Delta House motto, Ars Gratia Artis—“Art for art’s sake.”

And so, like a more-dedicated student than anybody in the movie, you consider the various contexts that art and literature and history afford, and come to your informed conclusions.

Professor Aronson’s verdict: “Probably it’s best to forget Animal House, although it’s really hard not to love Otis Day and the Knights.”

—By Jason Stone, University Communications

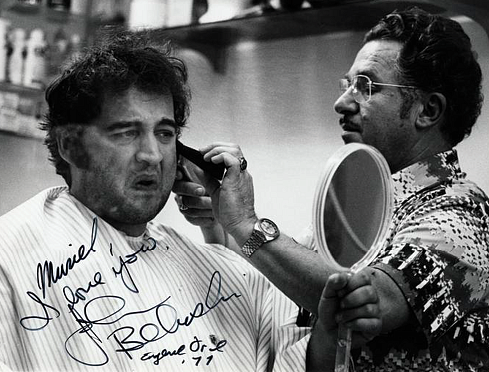

Photos courtesy of University Archives Photographs, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries