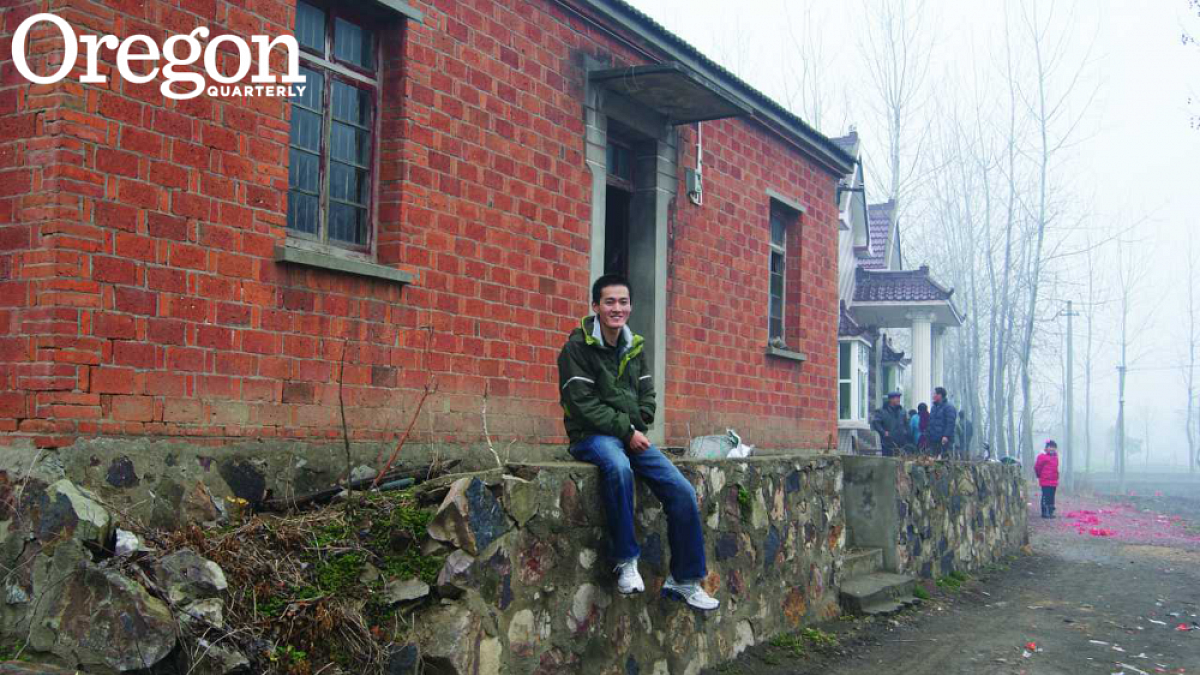

A giant watermelon slice is painted on the water tower in Hermiston, Oregon, a town of around 17,000 residents nestled amid rolling farmland that ripples endlessly across the Columbia Plateau. Fueled by agriculture and food processing, it’s the kind of down-to-earth place where farming, family, and high school sports form a stable backbone. Embrace it, and you fit in.

Growing up on those sandy plains of Eastern Oregon, Wyatt Harris ’12 was very much a son of the American West. His upbringing was woven with the sturdy threads of church and school, wrestling and Rotary Club, and fireworks on the Fourth of July.

But he was also something more.

Chinese by birth, he was a demographic curiosity. The nation’s controversial one-child policy had flooded China’s orphanages with baby girls, but it was unusual to find boys, who remained culturally prized.

Then, there was Wyatt.

Childhood photographs show a bright-eyed boy with a winning grin, as fine-boned as a fledgling bird. What the images don’t show are his limbs. Wyatt’s left arm ends abruptly at his elbow in a soft knob of flesh, a birth defect that the orphanage was reluctant to reveal.

Cal and Midge Harris couldn’t have cared less. They happily adopted the four-year-old, raising him first in Baker City, then Hermiston. There, he found a good life—a great life, really. Yet deep within Wyatt Harris resided a quiet urge to understand the shadowy beginnings of his own life.

Beneath it all, one question: Why was I abandoned?

The search for an answer would lead him on an extraordinary journey to a distant culture, a past he never knew, and a future no one could have predicted.

![]()

Everyone has a story.

This much he knew: In 1994, Cal Harris arrived at the Ma’anshan City Social Welfare Institute to adopt a son. Back in Baker City, he and his wife, Midge, were already raising a six-year-old daughter, Margie, from Colombia. This time, the adoption agency had steered them to the country with the greatest need: China.

Wyatt, they decided, would complete the Harris family. They knew only that Wyatt was about four months old when he arrived at the orphanage, though child welfare officials had guessed at his birthdate. He’d been abandoned, bound in blankets against early spring temperatures and tucked inside a basket left alongside a portable toilet near a soccer stadium.

China’s one-child rule was implemented in 1978 to curb growth in a nation that had seen its population nearly double from 1949 to 1976. But the policy cast a dark legacy—an upswing in child abandonments, gender-selective abortions, and even allegations of child confiscation by family-planning officials. No one knew where Wyatt fit into that picture.

From the beginning, Cal and Midge refused to see their son’s disability as a barrier—a view helped by Wyatt’s tenacious personality. When an occupational therapist tried teaching the boy to tie his shoes with one hand, Midge recalls, the youngster instead devised his own better, quicker method. “You have to know Wyatt—when he’s determined, he’s determined,” explains Midge, who works for an education service district in Hermiston. When Wyatt tried tennis, he not only mastered it, he won tournaments. Wrestling, soccer, T-ball, basketball—he did it all. He was a fast learner, adventurous, inquisitive, big-hearted, and open to the world, his parents discovered. “We expected both kids not to let things get in their way—if someone gives you guff, prove them wrong,” recalls Cal, who works at the Two Rivers Correctional Institution in Umatilla.

The angles of his face, the stub of his arm—Wyatt knew he was different. But he owned it, even joked about it. “I like to tell people I grew up in a town so small, there were only five Asians—the four people who worked at the Chinese restaurant, and me,” he laughs. Margie Harris had no desire to know more about her biological roots. Wyatt was a different story.

![]()

It was during his junior year of high school that he heard China calling.

Through Rotary International, Wyatt had an opportunity to study in Taiwan, an island of 18 million people that lies just off the southeastern coast of China like a plump yam tossed at sea.

The Harris family had hosted students from Mexico and France through the Rotary Youth Exchange Program, and believed in it. They knew Taipei would provide a good experience. Wyatt saw a chance to learn about his own distant culture, to feel what it was like to walk down streets crowded with Asian faces. Once there, enrolled for 11 months of study at a vocational high school, he began learning Mandarin, making no secret of the fact he was adopted from China. Someday, Wyatt knew, he would be back.

By the time he returned to Hermiston High School for senior year, Wyatt already knew he was headed for the University of Oregon. Aunts, uncles, cousins—so many relatives had gone there it was simply an accepted rite of passage. By taking college-credit classes in high school, he entered the UO as a sophomore intent on majoring in Chinese and international business.

Maram Epstein, an associate professor in the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures, recalls Wyatt standing out in her Chinese literature class as an eager student, hungry to learn and willing to dive deep into the subject. Much of the reading that term focused on classic themes, including filial piety, the foundation of Confucian society that speaks to the respect, obligation, and love a child owes a parent over his lifetime. She noted Wyatt’s interest, but wasn’t surprised. “We have a lot of students from East Asia who’ve been adopted in the U.S. taking courses because they’re trying to figure out something about who they are.”

Epstein never spoke with Wyatt about his arm, but she knew that China still carried cultural taboos around birth defects. “In early Chinese texts, it was considered extremely inauspicious if a child was born in some way that was irregular,” she says. “In fact, it’s still very hard to have an obvious disability in China—a lot of places won’t hire you, certain schools won’t take you, you are cut out of a lot of opportunities.”

When Wyatt learned of study-abroad opportunities through the UO Office of International Affairs, he was intrigued. By 2010, he was off to study Chinese and business management for a year at National Taiwan University. He had unfinished business. With mainland China only about 100 miles to the west, the chance to learn more about his roots was tempting.

Then, an opportunity. Traditionally, the Chinese New Year is one of that country’s most important celebrations, triggering more than a month of holiday travel often described as the largest annual human migration in the world, as hundreds of millions of residents find their way back to home and family. On January 30, 2011, Wyatt Harris joined them.

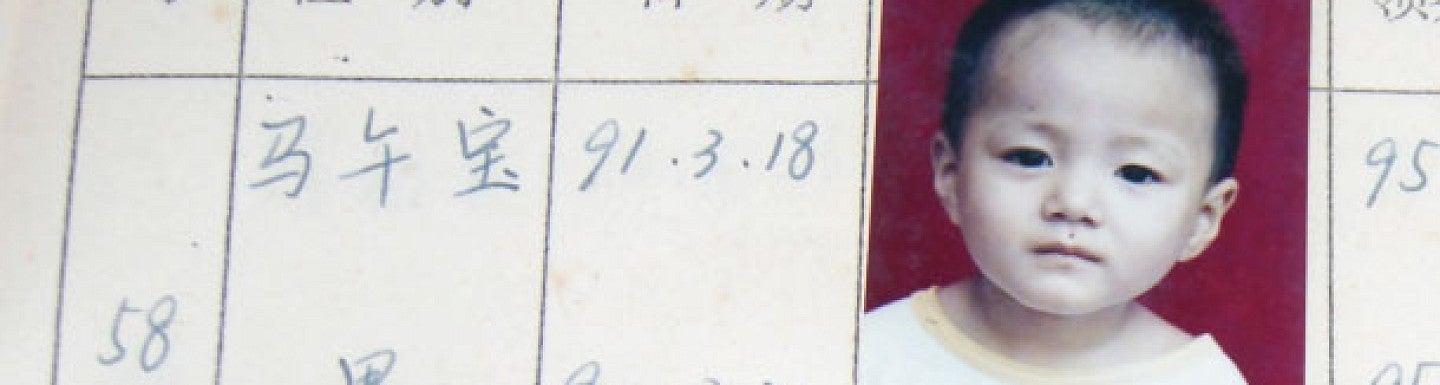

![]()

There was little to go on: the name of a city and orphanage, a few photographs, some random documents—but even that was more than many Chinese orphans had to work with. Wyatt landed in Nanjing with a backpack, just enough language skills to get by, and no real plan.

Located in eastern China along the banks of the Yangtze River, Ma’anshan is one of the nation’s brawny steelmaking cities, home to more than a million residents. Wyatt was struck by the incongruities—this beautiful urban setting, its ancient bones glowing beneath holiday fireworks, was also home to elderly beggars who held out dirty tin cans.

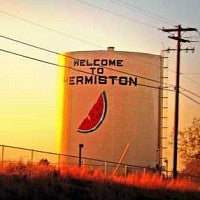

The next morning, Wyatt was in a taxi heading for the Ma’anshan City Social Welfare Institute, and feeling nervous. The gated complex was clean, attractive—nothing like what he expected. Wyatt introduced himself by his Chinese name, Wamubao, the one they’d given him at the orphanage. A caregiver shouted, calling to others. How could they possibly remember him? But there he was, remembered and celebrated and embraced. Over the babble of dark-eyed babies, Wyatt laughed and asked if he’d been that talkative. “Oh yes,” the caregivers insisted. It was a small detail, but for the first time, a crisp, tangible fragment of his own cloudy history.

The next day, Wyatt returned to meet with Chai Zhonghao, his primary caregiver, a woman he knew only by her photograph. She greeted him warmly, suggesting he enlist the help of local media to find his biological family.

He wasn’t the first to try. After a generation of overseas adoptions—more than a quarter-million children by some estimates—China has recently experienced a surge in foreign adoptees returning to learn more about their beginnings, spawning a cottage industry of “root-seeking” tours, culture camps, and orphanage reunions.

After an afternoon meeting with other orphanage “siblings,” many of whom still remembered him, Wyatt found himself alone in his thoughts, walking past a radio station. It was fate, he decided.

The station was protected by a fence, but no security guard. He took a chance, entering the 22-story building and randomly pushing elevator buttons. One floor, then another. No luck. Giving up, he left—only to be met by an angry guard. Observing Wyatt’s curious behavior on a security monitor, the guard assumed he was a burglar. As Wyatt frantically tried to avert an international incident, a young woman appeared, drawn by the commotion. Lisa was a DJ at the radio station Wyatt had been trying to locate. Hearing his story, she reassured the guard, and offered Wyatt a ride back to his hotel. Though interested in helping publicize the story of an American boy seeking his Chinese birth family, with the looming holiday, she thought it unlikely that his story could run for at least a week.

The birth defect that the orphanage had once wanted to hide was now something that made him stand out—a mark of distinction that would surely be recognized by his birth family.

Listeners wanted to share his story online. News outlets in surrounding cities wanted to broadcast it, too, in case his birth parents had moved. And no one wanted him to be alone during the holiday. He was stunned. In the most populous nation on earth—1.3 billion by the latest count—the chances of finding his biological family were beyond remote. But soon, his face was in the local papers. Strangers recognized him on the street, greeting him with a warm, “Welcome home.”

In only a few days, Wyatt Harris had become a top news story.

![]()

Early the next morning, a reporter called: She knew exactly where Wyatt had been abandoned and could take him there. He would have never found it on his own. After years of neglect, the soccer stadium had been demolished and replaced with an attractive park. As he watched children at play, for the first time in his life Wyatt felt something like anger toward his birth parents. He’d been robbed of such simple moments, the right to stretch out his toddler fingers to grasp their warm hands.

Next stop, a nearby police station to search for his child-abandonment records. They never got past the front gate. Record keeping had been abysmal that far back; everything was on paper, crammed into boxes. Most likely the records either didn’t go back that far or had already been destroyed, a skeptical officer advised.

Wyatt returned to the orphanage. Working with the director, he found his own photo, marked “Number 58.” A corresponding file contained a dusty, sealed folder—within it, a few photos and assorted documents, which lay before him like random pieces to different puzzles. Another dead end.

The days dissolved into a chaotic stream of media interviews, phone calls, and dinner invitations. But time was evaporating. With only three days to go until his scheduled departure, Wyatt returned to the police station where he’d been taken as an infant, shadowed by an entourage of at least a half-dozen journalists.

This time, they got inside. But again, officers were doubtful that records could help. “Tell me this,” said Wyatt. “If I were to abandon a child today, what process would you follow?” An officer produced a book containing the “receipts” of abandoned children—a system that had long been in place. The orphanage, the officer advised, might still have a matching receipt. Somehow, amid years of paperwork, it did. And with it, more details. A woman named He Wenyiu had found Wyatt on March 18, 1991, near Ma’anshan Stadium. Though she had died in 2005, officers were able to locate her son, who had been with his mother when she found an infant that day.

Wyatt was handed an address and phone number: “They want to see you tonight.”

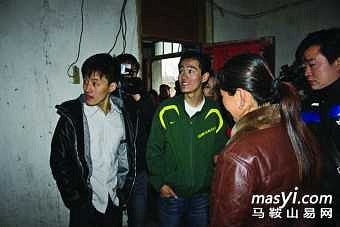

Trailing a now-familiar entourage of reporters and cameramen, he entered a small, modest apartment to find an elderly man, easily in his eighties, and his grown son. As the man spoke, the past eased into focus:

The family had been out walking the day they found Wyatt. Many had passed his basket without a glance, the man, now a grandfather, recalled. But when his wife peered inside, she was shocked to find an infant; he hadn’t so much as whimpered. If they didn’t already have three children, the grandfather insisted, “we would have kept you as our own.”

The old man’s words were a comfort, but offered few clues into his past. And he was running out of time.

![]()

Wyatt Harris had come to China as an American, a stranger. Eleven days later, he left with a face that even the cab drivers recognized.

Back in Taiwan, he decided to squeeze in some sightseeing before the start of a new semester. Gazing out a bus window, his thoughts kept drifting back to China. Checking his e-mail, he felt a jolt. It was a message from a Chinese newspaper reporter: “Good news. Your biological parents came forward.” He read it three times, even asking a nearby stranger to translate it, to be certain. After only 18 days and few leads, his search was over. Wyatt wept. With his right hand, he dialed his parents in Oregon. They congratulated and cautioned him, not knowing what he might find on the unseen pages of a hidden past.

Easing back into his seat, Wyatt noticed more e-mails. He opened one to find a photo of a young man. There was a distinctive chin, so much like his own. The bone structure, the smile—all remarkably familiar. His brother. Next, a sister with that unmistakable chin. Finally, a woman who could only be his birth mother. Many times he had imagined what his biological family looked like. In minutes, the weight of that mystery had lifted. “I knew it was happening, it was really happening,” he recalls. “I just couldn’t believe it.” Days later, a DNA test would confirm what Wyatt already knew.

His first contact was a brief phone call. Wyatt introduced himself by both his American and Chinese names. “Are you my biological mother?” he blurted in Chinese. The phone was quickly passed to an uncle.

Next question: “When was my birthday?”

His birth mother spoke up, nervously explaining that she was illiterate and not good with dates. But she remembered: December 20, 1990. A midwife had come to her house; there had been no official record of the delivery. December? The realization hit him. Wyatt must have been with his biological parents for several months before they abandoned him. He asked for his original Chinese birth name, but the answer was hard to take. They had never named him.

![]()

During the descent into Nanjing Airport, doubt began to sink in: What was he doing? Wyatt closed his eyes, asking God to help him get through whatever awaited him.

Winding through customs, Wyatt felt panicky. He could already hear unfamiliar voices shouting, “Mawubao! I see Mawubao!” He wasn’t ready. He slipped into a bathroom to splash water on his face and apply more deodorant—he was already sweating beneath his University of Oregon jacket. A deep breath, a few more steps, then faces that he recognized: Lisa from the radio station, the reporters, the cameramen—and his birth mother, a small woman in an oversized leather bomber jacket, pushing her way through the crowd to seize him. She clung to Wyatt’s good arm, sobbing like a frightened child. Reporters shouted a torrent of questions; Wyatt has no idea what he told them.

A tap on his shoulder. Wyatt turned to find the face of his big brother, whose eyes were already red from crying. Grinning, they hugged and studied each other, as if gazing into a mirror clouded by time. Then his younger sister appeared, a pixie with a sweet, playful smile.

Outside the terminal, his birth mother still clung fiercely to his right arm, plastered against him like a wet leaf. The plan was to drive to a hotel, which had donated a meeting space. After all these years, Wyatt needed some answers.

Along the way, he chatted with his new siblings. His brother had never attended college. In fact, neither sibling had graduated high school. It hit him like a swollen wave—this would have been his life, too.

Had his brother known of Wyatt’s birth? Yes, from a fairly young age. His brother began to cry. Maybe Wyatt wasn’t the only one haunted by the past.

Finally, it was time for the media to leave. How to begin? First, he expressed his appreciation. His family didn’t have to come forward, but they had. “For that, I thank you,” Wyatt said. Then Wyatt looked into the eyes of his birth parents: “The answers you give me will not at all hinder our relationship,” he assured them. “I just want to hear the truth—if you tell me the truth, it will only make our relationship stronger for the years to come.” With a nod from his birth father, Wyatt began:

“Why did you leave me on March 18, 1991, at the stadium?” It was the very soul of his journey, the reason for this search.

His birth father cleared his throat. They had been so poor. He made little money—perhaps $3 a week—and his wife had no job. For three weeks, the family struggled. By January, they were wrestling with a bitter decision: Love this child and fight to keep him alive, or give him to someone to find a better future, releasing his destiny to the winds of chance.

The decision was wrenching. They took a 30-minute car ride, first planning to abandon Wyatt in a small city near their rural home. They hid nearby to watch. Overwhelmed, his birth mother couldn’t bear it, retrieving him after 10 minutes. His birth father recalled holding Wyatt’s small body against his chest all the way home, his weight a warm reminder of where the child belonged.

“Did you know I was at the Ma’anshan Welfare Institute?”

Again his birth father spoke haltingly: “Yes.” Head down, he described eventually finding a better factory job not far from where they’d left Wyatt. After work one day, he passed a nearby orphanage. By then, it had been a few years since they’d abandoned him. Curious, he walked inside. There, in the corner of a courtyard, he spotted a small boy missing part of his left arm. Wyatt’s birth father admitted that for the next year he had visited Wyatt often, never once revealing his secret until one day, the boy was gone.

“Why did you reveal your identity?”

“You are our son; you deserve to know who your parents were for four months and why we did what we did,” his father explained. For Wyatt, it was enough. “I could see the anguish and regret,” he recalls. “From that point on, my task was to somehow find a way to tell them they didn’t need to feel guilty.”

![]()

The van rattled to a stop. Looking out, Wyatt took in the misty, winter-bare landscape, which lay like a muted watercolor, rugged and raw. Before him stretched a crude gravel road cut between murky pools the color of stout black tea—fields flooded for rice paddies.

His biological family piled out, their excitement palpable. Wyatt’s brother began chattering in rapid-fire banter: “Do you like to exercise? Do you like to run? Let’s run to our house!” It was a brother’s challenge. “Three, two, one . . .” he chanted. Like small boys, they tore down the lane, racing toward a distant cluster of buildings. Legs pumping, Wyatt could hear voices chanting his Chinese name, “Mawubao! You’ve returned!”

Then, fireworks, an explosion of noise and sparks showering upon them, flowering blossoms of pyrotechnics. At the end of the road, more than 100 cheering people had gathered to greet him, smiling, hands reaching to embrace him.

Inside his family’s modest house, he was met with hugs and handshakes, a parade of food and happy toasts of strong rice wine.

Over the next three days, Wyatt observed the life he might have known. It was sobering. His biological father worked at a shoe factory in a distant province, typically gone from home 11 months out of the year. His birth mother worked in neighboring rice fields. His brother had just taken a job at a printing plant. His sister was a masseuse. While his biological family had achieved financial stability by local standards, saving for years to build their modest farm home, they wanted to show Wyatt how far they had come. It was a shock. The house he was born in was a shanty barely the size of a college dorm room.

The second day, they visited an ancestral burial site to give thanks for the reunion. From his studies of Chinese history and culture at the UO, Wyatt knew it was a ritual to be taken seriously.

While uncles pulled weeds away from a tombstone, Wyatt was handed Chinese ceremonial paper money. Kneeling, he watched his older brother, copying him as he folded, then unfolded each sheet of yellow paper, placed it on the cement pad, and lit it. As the papers burned, thin fingers of smoke floated toward the heavens, a symbolic fortune sacrificed to unseen ancestors. As Wyatt helped feed the fire, he grew reflective. This was his birth family, his other family. What would become of their relationship after he left? But just then, his brother motioned him to another burial site.

“This is Dad’s dad, our grandfather,” his brother said, explaining that there were two types of tallies on the tombstone: one row of marks represented each of the deceased’s children, another tallied his grandchildren. When his brother grew quiet, Wyatt knew why—his grandfather’s tombstone bore only two tally marks. By ancestral tradition, it was if he’d never existed. Wyatt would have to make his own mark in the world.

As quickly as the reunion began, it was over.

At the airport, his biological father handed Wyatt a letter for his parents in Oregon, conveying his gratitude. Barely literate, he had dictated his appreciation to Wyatt’s brother, who’d typed it. He confessed that he’d had trouble sleeping lately; there was much on his mind and in his heart.

Stopping, the man’s eyes filled with tears. “I’m sorry,” he finally stammered. Wyatt absorbed the fragile weight of those words. They washed over him like healing waters, a soothing balm to his years of confusion. For a moment, he recalled the life he’d found in Oregon. It had changed everything.

“Don’t be sorry,” he explained. “Be grateful. Because of what you did, I now have an education, I have a future that I can call my own. Because of what you guys did, I have a family that loves and supports me and pushes me to be a stronger person every day. Don’t be sorry,” Wyatt added. “Be happy for giving me a second chance.”

A second chance. With those words, Wyatt would share the same message with thousands of new graduates and their families this June, when he appeared as one of three student graduation speakers during the Class of 2012 commencement exercises in Matthew Knight Arena. Looking across the vast, joyful crowd that day, he spoke of the power of second chances with the calm acceptance that comes from understanding your own past.

Everyone has a story. Some of us just have to go looking for it.

—By Kimber Williams

Kimber Williams, MS ’95, covers faculty and staff news at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. Her last piece for Oregon Quarterly was “Freedom Can’t Protect Itself,” in the Winter 2011 issue.