Every day, more than 144,000 drivers cross the Glenn L. Jackson Memorial Bridge linking Oregon and Washington on Interstate 205, but if you took a poll, not one in a thousand could identify Glenn Jackson—aka "Mr. Oregon."

Arguably the most powerful nonelected citizen in Oregon history, Jackson was a champion both of interstate highways and the environment. Advisor to five governors, countless senators, generals, and business leaders. Developer of state parks, a golf course, and a ski area. Founder of an airline. Builder of an industrial park. Owner of nine newspapers. Executive of the Northwest's largest power company. All that, and a lot more.

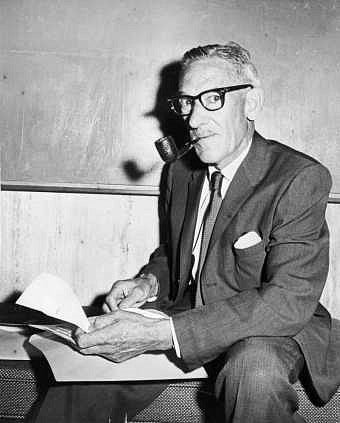

Jackson, son of the copublisher of the Albany Democrat Herald, was born in Albany, Oregon, in 1902. According to his 1942 War Department I.D., as an adult he stood 5'8", weighed 135 pounds, and had brown hair and eyes. Add to that an Errol Flynn mustache, slicked-down hair, black-framed glasses, and robust nose, and you have a true Oregon character. With his feet up on his desk and hands behind his head, he was a force—a man whose telephone calls were always returned and whose call for a meeting was always honored.

As a rebellious youth, Jackson once pulled his own tooth rather than wait for the absent dentist's return. An indifferent student, he was admitted provisionally to Oregon Agricultural College, managing to graduate with an engineering degree. Thereafter, he got a job with Mountain States Power Company selling flat irons and electric stoves, and proved himself to be a whiz of a salesman. At a promotional meeting in Wyoming, Helen Simpson, who also worked for the power company, saw him and said, "I am going to marry that man." And she did.

As president of the chamber of commerce for the Rogue Valley, Jackson came to the attention of General Ira Eaker, commandant of the 20th Pursuit Group of the Army Air Corps. It was about six months before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Eaker was looking for a place to train troops and pilots, and Jackson impressed him by procuring the Elks Picnic Grounds along the Rogue River. "He came the first morning to see what Medford could do to make our stay more pleasant," recalled Eaker. "I suggested a boxing ring would be helpful, and perhaps a little entertainment in the evening. Before sunset, we had a boxing ring, well lighted, also an outdoor dance floor, and each evening a choir or barbershop quartette came out to entertain us. Some nights many local belles came out to dance with our young fliers."

The general knew talent when he saw it, and Eaker requested Jackson's services in England, giving him a job doing what nobody else either wanted to do or could do. The 8th Air Force had units scattered all over England, and Eaker needed a central hub. To house this operation, Jackson "built a large Nissen hut, cut the top out of it with blow torches and superimposed another Nissen on top of it. The Americans called it a 'Jackson highrise.'"

When Eaker was transferred to Italy, he did not think it "safe" to leave Jackson in England; besides, he thought he just might need some "special projects" in his new theater of war.

Eaker planned to locate his Italian headquarters in an old palace that had been used as a training school by Mussolini's air force, which the Italians said they could vacate in a month or so. But they didn't know Jackson. By the next morning the equipment used by Mussolini's school—engines, charts, diagrams—was lying in the courtyard, having been thrown out the windows. Eaker's desks, maps, typewriters, and communications equipment were set up and ready to go. Eaker quipped that he was glad he had never mentioned the Sistine Chapel to Jackson.

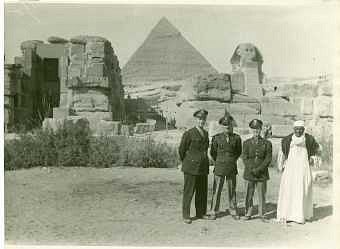

The Medford Mail Tribune posted a picture of him, in uniform, in front of the Sphinx in Egypt, noting that, "While the Sphinx had been silent for centuries, it was heard to utter: 'Whew' after Jackson breezed on."

Jackson paid the Southern Pacific Railroad $100,000 to run a spur line, the deal being that he would be reimbursed at $15 for each car loaded out. He got his investment back the first year. The Medco sawmill ran a log train up to Butte Falls every day, and by 1959, 20 industries shipped 1,000 cars a month out of White City. And a city it was, with its own fire department, maintenance crew, telephone exchange, five plywood plants, two molding manufacturers, a paint factory, dress shop, and bottling facility. In all, it provided more than 1,600 full-time jobs.

In 1946, with partners Wally Graff and Marshall Bessonette, Jackson acquired the golf course in Medford (now the Rogue Valley Country Club), of which he had been president since 1935. He wanted it to be a family recreational facility, open to average people. It had a board of directors, but the vision and operation of the club were Jackson's alone. His close friend Warren Bayless recounts that a newly elected president of the board wanted to meet Jackson. The exchange was: "I'm the new president of the board." Jackson: "Delighted to meet you. Just remember, I run the place." Every time the board would try to raise the "ridiculously low" dues, Jackson would veto it. If the club needed money, Jackson would provide it.

In April 1959, Governor Mark Hatfield appointed Jackson to the Oregon State Highway Commission, and his influence over the future of the state was made manifest. Over Jackson's 20 years on the commission (later the Oregon Transportation Commission) he had at his disposal almost $1 billion to invest in bridges, freeways, connectors, and tourism.

He became chairman of the three-person commission in 1962, and by 1967 Oregon had completed the highest percentage of its planned interstate highways of any state in the nation. Jackson deemed it "the greatest contribution we could make to the development of the state," and said the availability of federal highway funds was a "golden opportunity."

He was passionate about Highway 101 along the coast, saying that you can't promote tourism by scenic beauty alone—you need housing, recreational activities, and food, and you have to control litter and air- and water-pollution. Oregon's people, he said, have to step up and realize that these problems are all of ours and we are the solution.

Jackson was used to getting his way. He brokered the I-5 route up Bear Creek and essentially over the top of Medford, pleasing almost no one, and he supported a proposal to run Highway 101 along the Nestucca Spit, which he lost, fortunately. But he also presided over the construction of I-205, I-405, the Marquam and Fremont bridges in Portland, the I-205 bridge in Oregon City, and almost every other major road Oregonians drive today.

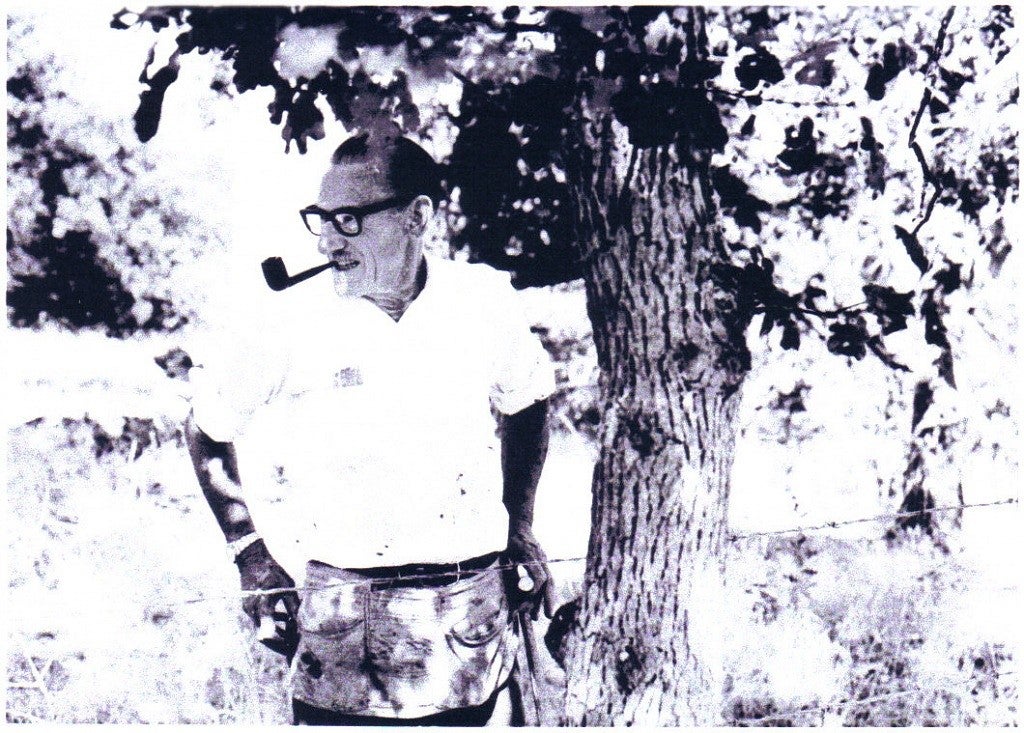

So what manner of man was this who got so much done? He was never without his pipe, and he apparently never threw one away, because one had a Band-Aid on the bottom of the bowl. He drove a black 1949 Buick turtleback that was so completely unadorned it didn't even have white sidewall tires. His lunch, when he was horseback riding with his friend Frank Bash, was always Underwood deviled ham on white bread and coffee (he drank no alcohol at all).

His work clothes, like his golf clothes, were shabby to the point of being disreputable. He was devoted to Helen, his wife of almost 50 years, who was a very capable person in her own right, educated at Stanford with graduate work at Nebraska in drama and journalism. He loved to read Louis L'Amour books, and drove a D8 cat around his 12,000-acre ranch near Eagle Point, much of the time building reservoirs and canals to retain runoff and reuse it for irrigation.

He said he got into the cattle business because he got interested in land-use problems. All of the water rights were spoken for, but his idea was to find areas that were suitable for storing floodwater so he could reuse the water and convert dry land to pasture. Once he did that, he asked himself what to do with the pasture. "Being of enquiring mind," he said, "I've been experimenting with crossbreeding in hopes of developing a better beef animal. I took some of our senior senator's prize Devon stock [the senator would be Wayne Morse, with whom Jackson was great friends] and have been crossing it with Hereford and Angus to see what we get. . . . A three-way cross could develop a beef animal of a superior type...It is a lot of fun and a lot of work."

Jackson was shy but also fearless. He answered his own office phone, always on the speaker without regard to who was in the room. No secrets. He would play poker all night with his friends, but otherwise he couldn't sit still. He played golf, usually with the pro as his partner, but would not talk business on the course. Ever.

He wasn't impatient; he was just fast, says his granddaughter. He expected everyone to do what he said and it just didn't enter his mind that you couldn't. He never put on airs and his friends were people of every race, religion, and age. "He would get people who should hate each other to work together," said Bash. "It always sort of amazed me." But he certainly did not suffer fools.

We know what he accomplished: He built the finest highway and park system in the country; raised money for the Oregon Symphony and St. Vincent's hospital; championed the Boy Scouts; created opportunities in business for the underprivileged; supported 4-H, the cattlemen, and agriculture; developed the Mount Ashland ski area (later given to Southern Oregon University) and the Rogue Valley Country Club (given to Willamette University); promoted tourism and protected the environment; worked for the Willamette Greenway, the beach bill, and the bottle bill; and the list goes on. Governor Straub said: "As long as Oregon is Oregon, Glenn Jackson's name will shine with luster as a person who has done more than anybody else to improve this state and to benefit the people of this state." The far more difficult question is, how did he do it?

He relished using power but understood its limitations. Look at his early years in Medford as the head of the chamber of commerce, where he recognized that a war was coming and a training base would funnel loads of money into the valley. When he was working for General Eaker, he must have been in hog heaven because, during wartime, there were few of the usual restraints on his use of power. Need a truck? Acquire one. (Paint over the Navy emblem and it belongs to the Army.) Need pews for the base chapel? Take one from every church in Naples. Power was to be used, and he was a master at it.

He was a good judge of talent and he would "mentor" legislators—not just so he could get money for roads, but to make them more successful lawmakers. He was friends with Wayne Morse, Mark Hatfield, Bob Straub, Tom McCall, and Vic Atiyeh—and always he worked with them, rather than for them.

Knowing his limitations and those of his network of allies, Jackson seldom undertook a task he could not complete. He worked well within the power structure of the state because he was flexible, competent, and had an ego that did not require a lot of care and feeding.

Almost everyone who knew him said Jackson never asked anything for himself. He took nothing, not even expenses, for his work on the Highway Commission. He ponied up his own money to keep the golf club going rather than raise the dues. When he invited 10 cronies to the Arlington Club in Portland on behalf of the symphony, he said, " Each of you write a check for five figures and we'll all have a nice lunch." Of course they did, because they knew he had already written his. "He's a man whose motivations are as pure and unselfish as any person I have ever known," said Don Frisbee, who worked for Jackson for well over a decade before succeeding him as chief executive of Pacific Power and Light. "It makes you feel good just to know him, just to think of him."

He could bring people of diverse beliefs and interests together to work for a common cause. In the early 1960s, a group of civic supporters in Portland decided to make a bid for the 1968 summer Olympics. With Jackson at the head of the pack, they solicited and received endorsements from governors of surrounding states, identified Delta Park as the venue, extended an official invitation to the XIX Olympiad Committee, and most impressively, got a pledge from the head of local labor that there would be no work stoppages or strikes during training and the games. The games went elsewhere, but for labor to cuddle up to business and promise peace was quite unusual. For Jackson, it was business as usual.

He almost always sided with the underdog, and inspired a kind of loyalty that made people feel protective of him. Perhaps it was because he didn't talk much and therefore didn't give away a lot, but he had that indefinable charisma that made people feel as if they were in on something really terrific.

A window into the inner man was in his relationship with Reverend D. Kirkland West, pastor of the First Presbyterian Church in Medford. Kirk West was a gregarious former footballer and missionary in China, who came to Medford about the time Jackson returned from the war. West wanted to know why Jackson didn't come to church more often, and Jackson responded that he didn't like the format of not being able to talk back to the minister if he had a question or disagreed with what was said. What resulted was the Sinner's Breakfast, where a group of men met at the Country Club for breakfast at 7:00 a.m. each Sunday morning with an assigned Bible verse. West would read the verse, make his comments, and then they would "tear me apart," he said, adding that he learned a lot from "those boys."

Perhaps it was the time in which he lived, perhaps it was his unique genius, but it is unlikely we will see another person with such a profound effect on this state.

Jackson was "Mr. Oregon" because he had vision and he translated that vision into reality, be it rest stops on I-5 or development that will never happen on the Oregon Coast. He sought no honors or recognition for himself, but was uncharacteristically ebullient—enough so to call his wife, daughter, and granddaughter travelling in Scotland—when he heard that the I-205 bridge was to be named after him. The bridge has a low profile because of its proximity to the airport flight path, and like the man it honors, it is functional, efficient, and unadorned.

While Jackson wasn't much of a speaker, he was not without eloquence, and a draft of a speech, probably about 1970, summarizes his philosophy:

"An educated society is one that acts dispassionately, votes intelligently, respects cultural and literary excellence, rejects yahoos, abhors bigotry, and admires scholarship. It perceives richness in leisure as well as in work, understands the past, transmits a sense of human decency and compassion to new generations . . . and knows enough about freedom to protect it."

Sound advice from Mr. Oregon. Someone should flash it on a reader board for the millions who cross his bridge.

—By John Frohnmayer

John Frohnmayer, JD '72, is a retired lawyer and former chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, the Oregon Arts Commission, and Oregon Humanities. John and his brother Dave, president emeritus of the University of Oregon, worked for Glenn Jackson at White City picking up trash and watering trees in the mid-'50s.

The author would like to acknowledge the help of his friend and colleague, Barbara Mahoney. Quotations in this article are from the following sources:

Medford Mail Tribune editorial, June 22, 1980.

Oregon Historical Society papers of Glenn Jackson, donated by Helen Jackson.

Interview with University of Oregon President Emeritus, Dave Frohnmayer, November, 2013.

Interview of Frank Bash by Mark Flinn, May 17, 1991.

Memories of Glenn Jackson by Lt. Gen., USAF (Ret.) Ira C. Eaker. Oregon Historical Society papers of Glenn L. Jackson.

"Glenn Jackson: There's a Man Behind the Myth," S.G. Radhuber, Northwest Magazine, Sunday March 20, 1977.

Interview of Frank Bash by Mark Flint, May 17, 1991.

Interview of Warren Bayless by Mark Flint, February 5, 1992.

Interview of Don Warnick by Mark Flint, February 6, 1992.

"Glenn L. Jackson, King of the Road," by Maggie White, HOME Magazine, July 13, 1966.

Interview of Leslie Ford-Brown, granddaughter, by Mark Flint.

Monograph, McKee, Jackson and Me, by Don C. Frisbee, September 6, 2001.

Salem Statesman Journal, Saturday, June 21, 1980.

Oregonian, article by Gregory Nokes, April 8, 1987.

Tribute to Glenn Jackson by Allen Hallmark, Medford Mail Tribune, June 22, 1980.