Catherine Johnson-Roehr ’80, MA ’89, leads the way between narrow rows of metal bookcases. The lighting is a bit dim, the ceiling rather low, the industrial cases dull and worn from decades of use, their shelves laden with books, boxes, and files. The key to navigating the shelves’ contents is carefully typed out on a sheet of yellowed paper:

500 Science

520 Sex Behavior

527 Sex Behavior, Aggressive

528 Sex Behavior, Disorders, Diseases, Disabilities

532 Homosexuality

535 Paraphilias

540 Sadomasochism

It’s a decimal system that might make Melvil Dewey do a double take.

But we are, after all, in a library. The library and archives of the Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction, to be specific. And Johnson-Roehr—who earned a BA in sociology, certificate in women’s studies, and MA in art history at the UO—is describing the institute’s unique collection of art, artifacts, and photography, which she has curated since July 2000.

“The mission of the institute is to pursue research that produces reliable information about human sexuality, gender, and human reproductive issues,” says Johnson-Roehr. “The mission is also very much about education. Our exhibitions allow people to see our collections and learn about the history of sexual expression in art from cultures around the world.”

Research and collecting were clear passions of institute founder Alfred C. Kinsey, who became a household name following the publication of his books Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (1948) and Sexual Behavior in the Human Female (1953). The books were unprecedented in their frank presentation of the breadth of sexual behavior, the result of thousands of personal interviews conducted by Kinsey and his staff. Kinsey began his career as a zoologist, and had amassed the world’s most extensive study collection of gall wasp specimens before his interest in biology led him to his groundbreaking research in human sexuality. The collection Johnson-Roehr now oversees originated in the service of that research.

Leaving the library and continuing through a series of winding hallways toward the institute’s gallery, Johnson-Roehr points out the prints and paintings hanging on the walls, some of them centuries old. “We have artwork from China, from Japan, we have a Persian collection (erotic artwork from Iran), we have Roman pieces. Kinsey wanted to write a book about erotic art, but unfortunately he died too soon.”

Kinsey died in 1956 at the age of 62, just nine years after founding the institute at Indiana University, where he was a professor. The collection, controversial by nature, was available to researchers but not widely publicized until the mid-1990s, when then director John Bancroft “got the ball rolling in opening up the collections,” says Johnson-Roehr. “He thought the library and collections should be used much more freely,” and supported the organization of the institute’s first large-scale exhibition of its collections as part of its 50th anniversary celebration in 1997.

Johnson-Roehr became curator of the collection a few years later. She and her partner (now her wife), Susan Johnson-Roehr, MA ’94, MA ’97, had moved from Eugene to Bloomington so Susan could study art history at IU. Having worked almost six years as a slide librarian in the UO’s School of Architecture and Allied Arts, Catherine found a job in the Lilly Library, which houses IU’s rare books, manuscripts, and special collections. When the curatorial position at the Kinsey Institute became available, she was a natural fit—with her library experience and degrees in sociology and art history, as well as a certificate in women’s studies from the UO (the program did not offer a major at the time), her background was ideal for understanding and appreciating the institute’s unusual assets.

She picks up a tiny comic book featuring Olive Oyl, Popeye, and J. Wellington Wimpy in ways never seen on Saturday morning cartoons. “These were popular forms of pornography in the ’30s and ’40s, known as ‘eight-pagers’ or ‘Tijuana Bibles,’” she says. “As you can see, they’re quite graphic! They’re just cheaply printed little comic books, the size of a wallet or pocket so they’re easily hidden away.”

There are also much more serious works in the collection. “This is one of our treasures, a hand-written letter from Sigmund Freud. It is a response to a letter from an American woman who had written to him because she was worried about her son, who was a homosexual. It was 1935, she probably didn’t know who else to talk to. Freud wrote this amazing two-page response saying that homosexuality was not a disease and that it was nothing to be ashamed of. It must have been such a reassuring letter for her to receive. It’s also Freud giving his opinion about homosexuality in his own words, so it’s a very significant letter.”

Johnson-Roehr has put her own mark on the collection with a focus on fine art and the inclusion of more works by women artists, such as Judy Dater’s well-known photograph “Imogen and Twinka in Yosemite,” which appeared in a 1976 issue of Life magazine. This fall, the institute will exhibit photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe, a gift from the Mapplethorpe Foundation. “We were a bit nervous when we announced the gift,” she says, “but nothing happened.” Bloomington is very close to Cincinnati, where the director of the Contemporary Arts Center was arrested in 1990 for exhibiting the artist’s sexually explicit works. Johnson-Roehr doesn’t find that too worrisome, though, saying, “We expect visitors to be pleased to have the opportunity to see so many examples of Mapplethorpe’s work.”

Perhaps Johnson-Roehr’s most successful effort to raise the collection’s profile within the art world is the establishment of an annual juried art show, now in its ninth year. “It’s been fun to see the way that show has evolved, and it has certainly benefitted us in terms of getting the word out about our contemporary collection and helping build that collection,” she says.

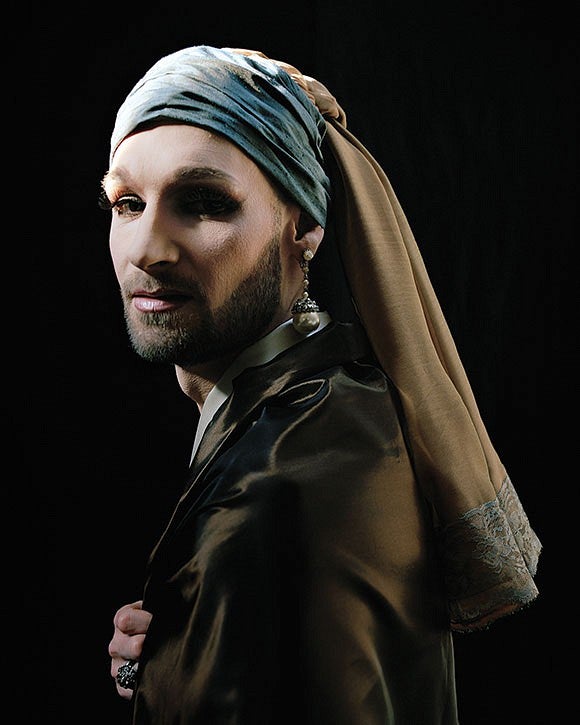

Chicago-based artists James Kinser and Niki Grangruth have shown their collaborative work in the juried show for the past five years. “Our work makes direct reference to art history,” says Kinser, referring to the duo’s “Muse” series, in which Kinser performs and Grangruth photographs representations of iconic art-historical works. “It's a great experience to walk down the hall and see the collection’s historical pieces in proximity to our own work. Some of these contemporary pieces are talking about gender in a way that has not been done extensively before. It’s expanding the conversation that is taking place within the collection.”

In the mid-20th century, Alfred Kinsey rocked the world when he convinced thousands of ordinary people to talk candidly about sex. In her own way, Catherine Johnson-Roehr is continuing that work, expanding the conversation through the objects and images in this singular collection.

—By Ann Wiens