Conrad Sproul looks up from the long table where he and his debate partner, Gracia Dodds, are hunched, side by side, reviewing their notes. It’s the first round of the 2018 David Frank Tournament of Scholars in February, a three-day collegiate debating contest hosted by the University of Oregon and drawing 20 teams from six schools across the Northwest. Sproul touches a finger to his phone, starting the timer, and his mouth explodes:

“WeproposethattheUSfederalgovernmentshouldsignificantlyincreaseitsdeploymentofnextgeneration . . .”

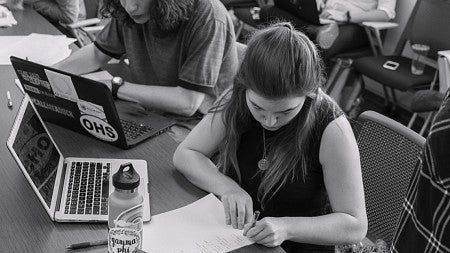

Sproul (above, second from left) is speaking roughly three times conversational speed—he has just seven minutes to frame and comprehensively support the proposal. He’s literally gasping for breath as he gallops through his staccato delivery. Dodds, at his elbow, is a portrait of calm: scanning her notes, jotting new ones, nodding when Sproul makes a particularly salient point. Sproul reaches the end of his argument at the very moment his timer goes off.

There’s a short break before one member of the opposing pair—students from Lewis and Clark College—launches into his take-down of Sproul’s case. This student speaks almost conversationally, gesticulating for emphasis, his voice rising and falling, much like a lawyer making a closing argument. His reasoning is easy to follow. Fact is, though, he just doesn’t seem to have as much to say. And in competitive collegiate parliamentary debate, it matters whether you hit all the pertinent points. At the other end of the table, Dodds and Sproul quietly confer, taking more notes, exchanging glances. By the time the beep-beep-beep sounds and their opponent wraps up, Dodds is smiling broadly, gathering herself for her allotted eight-minute response. Her expression is unambiguous: We got this.

Dodds and Sproul (below) are phenoms: freshman debate partners who, only four months into their college careers, trampled nationally ranked juniors and seniors from dozens of colleges to go undefeated at Pacific University’s Scheller Forensics Invitational, one of the biggest and most competitive tournaments in the Northwest.

But the freshmen dynamos are not anomalies. They’re part of a forensics program ranked among the best in the country, one that is nearly as old as the UO itself, and with as storied a history as any program at the university. In its earliest days, forensics was so popular that it helped fund the football team. It may be the most successful UO program you’ve never heard of. But there’s an argument to be made that, as a Duck, you should sit up and take note.

Find your voice

Competitive forensics is like public speaking on steroids: individuals or teams from one school pitting their skills of persuasion, argumentation, or advocacy against opponents from another. The Latin root of forensics, forensis, means “in open court” or “public.”

Participants in collegiate forensics specialize in one of three areas. Dodds, an environmental studies major, and Sproul, of political science, compete in parliamentary-style debate, with pairs of students squaring off on topics of contemporary concern. “Debate has given me the confidence to have a voice wherever I am and whoever I’m talking to,” Dodds says. “There are huge critical-thinking skills I’ve gained that have helped me get significantly better at writing essays and making presentations and even just talking with my professors. It’s given me the confidence to be who I am and to be unapologetically present in argumentation and conversation.”

Speech, a second area, encompasses a slew of subcategories—extemporaneous, theatrical, broadcast, and many more.

The third area, mock trial, is exactly what it sounds like: teams of undergraduates going head-to-head in a simulated criminal or civil trial. It requires 10-person squads and contests stretch across three hours, unlike debate’s series of four- to eight-minute bursts. And unlike the sneakers and hoodies (and occasional profanity) favored by contemporary college debaters, for mock trial think dark suits and “Yes, your honor.”

“We have students pretty much across every major,” says Director of Forensics Trond Jacobsen, BS ’02 (sociology)—“music, biology, computer science, theater, history, anthropology, everything.”

"Part of the UO's 'DNA'"

The UO was not even two weeks old when, in October 1876, student-run “literary societies”—one for men, one for women—held their first meetings in what is today 301 Deady Hall. They sound like book groups, but the societies were debate clubs—among the first in the country. Members met weekly to formally debate the issues of the day, men and women occasionally facing off against each other. Those debates quickly became the biggest cultural events on campus; the societies began selling tickets, spending the proceeds to support the fledgling football team and to buy a stack of books that became the genesis of the UO library’s collection.

Forensics is “part of the UO’s DNA,” says Jacobsen. He cites a long string of firsts: participants in one of the country’s first intercollegiate debates (against Willamette University in 1896), participants in the first debate broadcast on radio (against University of California, Berkeley, in 1922), first collegiate debate team to make a world tour (1927, a six-month undertaking). The program has had ups and downs—it’s 140 years old, after all—but it’s on a roll now, with 70 active members. In 2016, UO ranked 19th for mock trial among 650 teams from 350 US colleges and universities; individual debaters Liz Fetherston, BA ’14 (Spanish), and Alyson Escalante, BS ’16 (philosophy), took top honors nationally in 2014 and 2016, respectively. UO forensics also notched national championships in debate in 2001 and 2009, and a double national championship in 2011, when the UO won two national tournaments.

Jacobsen (right) has directed forensics since 2013, but his involvement stretches back to 1989, when, as a student, he debated for UO all four years. After graduating, he worked in politics and as a law librarian, then headed to the University of Michigan to pursue a PhD in information science. He accidentally stumbled across the job posting at Oregon while, mid-dissertation, he was on a search for professorships in his field.

He inherited a small program whose previous 10-year run had been as strong as any in UO forensics history. Under David Frank—who had been Jacobsen’s own director of forensics—UO had won four national championships.

But Jacobsen felt there was room for growth. He was particularly intrigued by mock trial, which at most colleges is only a club activity. Jacobsen made it a formal part of UO forensics; the UO is one of the few universities that materially supports both debate and mock trial, uniting them in forensics. Today, both are strong: five debate teams are travelling to nationals and outstanding recruits are enrolling next fall, while mock trial has grown substantially, with five 10-person teams active in competition.

Legally speaking

Niharika Sachdeva, a member of the class of 2018, personifies both the value of mock trial and the academic rigor of UO forensics.

Like Dodds and Sproul, the journalism major is a member of the honors college, which also houses the forensics program. That intertwining of the honors college, forensics and top students such as Sachdeva, Dodds, and Sproul underscores the demanding, scholarly nature of the program. Jacobsen notes, for example, that Robert D. Clark, the university’s eleventh president and the man for whom the college is named, had been director of forensics.

“Forensics attracts many bright students to the college every year,” Jacobsen says, “and many team members are in the honors college.”

Jacobsen says Sachdeva’s abilities and attitude have made her a “phenomenal” leader in building the forensics program, in general, and mock trial, in particular. “It’s not easy being a leader,” Jacobsen says, “and yet she does it with a high level of competence, in a way that makes everyone want to help her and the program succeed.”

Since taking over forensics in 2013, Jacobsen has overseen a five-fold growth in participation. He came into the program with a personal commitment to transforming what had traditionally been a male-dominated activity into one equally welcoming to females.

“Having personally experienced the value of forensics, how it furthers the intellectual and professional development of the person, their confidence, their ability to find their voice, I knew I wanted to build a program that would be open, encouraging, and welcoming to women,” he says. Among large college forensics programs around the country, UO is the only one with more female participants than male.

Jacobsen also revived an annual invitational college debate tournament at UO—the aforementioned David Frank Tournament of Scholars—and launched an annual mock trial tournament, the David Frohnmayer Invitational, named for the university’s 15th president. (UO forensics also hosts one of the longest-running high school speech and debate tournaments in the country, the Robert D. Clark Invitational.)

That's not all. Jacobsen began the Oregon Forensics Alumni Network, whose fourth annual dinner this year attracted more than 70 attendees and whose donations now enable UO to offer modest scholarships to promising debaters.

A recent gift from former debaters Greg Mowe, BA ’68 (mathematics), MA ’69 (speech), and his wife Becky, BA ’69 (speech)—whose dad Scott Nobles was a professor of rhetoric and UO forensics director in the 1950s and ’60s—will support both an existing scholarship in Professor Nobles’ memory and establish an endowment for a director’s fund.

“That we have people returning to UO 50 years later for this dinner speaks to the team-building you find in forensics, and the depth of those friendships,” Jacobsen says. “It’s deeply personal and a big part of a lot of people’s undergraduate experience. It was for me.”

Just as forensics has proven to be for Dodds and Sproul—win or lose. The pair went undefeated on day one of the David Frank tournament but failed to make the finals.

“It’s had a really positive impact on my freshman year, because I’ve had a small group of people that I can always talk with, which I don’t think a lot of other students have,” Dodds says. “Debate creates immediate friendships, because you’re spending so much time preparing together and half of your weekends together. You’re a little bit forced to be friends, but you also have very similar interests; you want to talk about the world and about philosophy. You’re learning together.”

“It’s never been super-easy for me to make friends; it’s just not my personality type,” Sproul adds. “So I really appreciate the sort of automatic social group that debate provides.

“You never run out of things to talk about.”

—By Bonnie Henderson

Bonnie Henderson, BA ’79 (English), MA ’83 (journalism), is the author of four books, including The Next Tsunami: Living on a Restless Coast.

DAZZLING DEBATERS

Generations of UO forensics members have used their skills to impact the world. A handful of standouts:

Carlton Savage, BS ’21 (history), had a long career with the US Department of State and was part of the delegation that established the United Nations. Among his accomplishments: articulating the legal foundation for civilian control of nuclear weapons early in the Cold War era.

William Knight, BL ’32 (law), served as a state representative from Douglas County and as district attorney for that county; he later spent 18 years as publisher of Portland’s afternoon daily newspaper, the Oregon Journal. His children include Nike founder Phil Knight.

Edith Green, BS ’40 (education), became the second woman elected to the US House of Representatives from Oregon. She helped pass Title IX legislation in 1972, which provides gender equity in higher education funding.

Wallace Campbell, BS ’32 (sociology), MS ’34 (economics), cofounded CARE, a major international relief agency, immediately after World War II, to provide emergency rations to starving people in Europe. He served as CARE’s president from 1978 to 1986.

Donald Tykeson, BS ’51 (business administration), a captain of the debate team, was a communications industry pioneer. He launched what became one of the largest cable television companies in the country, Liberty Communications, and helped found C-SPAN. He was a generous philanthropist, with gifts touching every corner of the UO.

TIPS FOR WINNING TIFFS

Are you going about arguing all wrong? Gracia Dodds and Trond Jacobsen, of UO forensics, offer advice on how to approach—and win—an argument:

FIND THE VALUE IN YOUR OPPONENT’S ARGUMENT

Asserting “nothing you have said has any merit whatsoever” gets you nowhere, Jacobsen says; it kills the possibility of constructive dialogue and it doesn’t tend to win arguments. Instead: identify, absorb, assimilate, and redirect: “You’re making some strong points; here’s why I think, overall, my argument is stronger.”

FACTS ARE OVERRATED

“The mistake a lot of people make is to think, ‘I just have to say the one damning fact, and there’s no way I can lose.’ That’s not true most of the time,” Jacobsen says. You have to be able to back up what you’re saying with facts, Dodds adds, but don’t lead with them: “If you’re just a robot spitting out facts, you’re not going to reel people in.”

APPEAL TO EMOTION

“Let people know that what you’re asserting is important, that it affects people,” Dodds says. Appealing to folks’ feelings often goes further than dazzling them with displays of logic.

BUILD CREDIBILITY

Citing authority—one that the other side knows and respects—bolsters your claim.

READ THE AUDIENCE

Adapt your speed, style, delivery, and even the vocabulary you use to your audience. Assess the opposition, Dodds says: “The way that I might talk to a professor is going to differ from the way I might talk with my parents.”