Before the 1963 civil rights march on Washington, volunteers at a New York church made 80,000 cheese sandwiches to bring to the protesters.

That room full of people industriously preparing lunch is one of the details that makes The March, a documentary by James Blue '53, so compelling. Blue made the 33-minute film in 1964 as part of a United States Information Agency (USIA) propaganda project to promote American ideals in other countries. The narrative of peaceful protest, the gospel songs, and the famous speech by Martin Luther King do not fail to inspire.

But it's those cheese sandwiches that stick in your mind: all the work, by ordinary people, that goes into changing history.

Blue changed history himself. He was a visionary filmmaker, creating works that pushed genre boundaries. Few people have ever heard of The March; or The Olive Trees of Justice, a French-language film that won the Critic's Prize at the 1962 Cannes Film Festival; or A Few Notes on Our Food Problem, another USIA documentary, which was nominated for an Oscar in 1968.

None of these films were distributed in the United States. The March, A Few Notes On Our Food Problem, and Blue's other films for the USIA were subtitled in many languages and screened around the world. But federal law forbade showing them in the U.S.; the 1948 Smith-Mundt Act banned American propaganda from being shown within the country. This didn't change until 1999, when the USIA was shut down.

An Oscar nomination for a film that had never been seen in this country? Blue's work was that brilliant—and that obscure.

Maybe that would have changed eventually. But Blue died young (in 1980, at age 49), of cancer. His work's obscurity seemed guaranteed—until about 30 years later, when some film buffs in Oregon found out about him, and everything started to change.

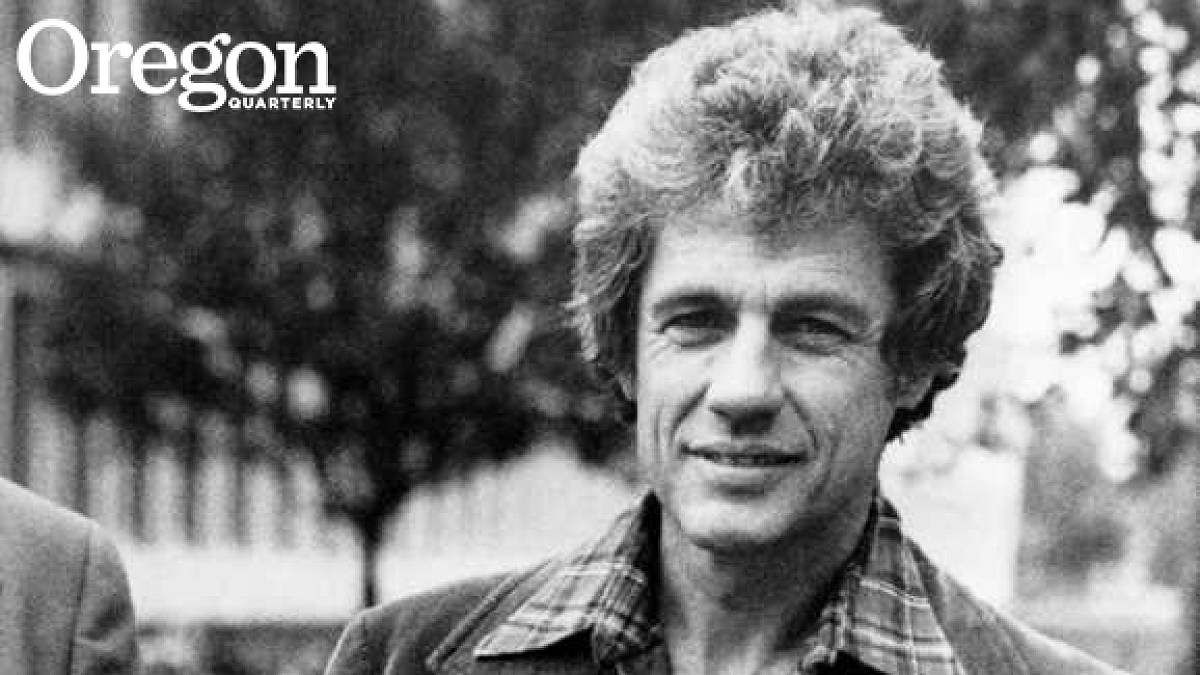

James Blue was a born showman. An acne-plagued teen who found his niche throwing bacchanalias with the Latin Club. A college radio personality who developed a deep, sonorous voice perfect for both late-night jazz shows and voiceover narration. A confident director with a feathered '70s hairdo and a killer smile. An apolitical creative type whose work had profound implications for social justice.

Blue messed around with making movies as a kid, filming his family's departure from Tulsa to move to Portland in 1942. (In the interest of narrative, he forced his younger brother, Richard, to kiss the neighbor girl on camera.) As a speech and theater major at the University of Oregon, he directed a 40-minute parody of Hamlet that was quite popular at the Student Union. But his career in film really started when he was a graduate student at the prestigious Institute of Advanced Cinematographic Studies in Paris.

His best friends in Paris were Marxist intellectuals, and their critiques of capitalism and America's foreign affairs came as a surprise to Blue. "My brother didn't have a political bone in his body," says Richard Blue. "He was not an ideologue. In fact, he was an anti-ideologue." Richard Blue was a political scientist who focused on international aid, and over the years he and James frequently discussed the social issues behind James's films.

Made by "an anti-ideologue" to promote American ideals abroad, Blue's USIA films were not simply propaganda. Some, like Letter from Colombia, poke fun at the clichés of the American propaganda film, says Richard Herskowitz, director of the UO's Cinema Pacific Film Festival and an instructor in arts and administration. A Few Notes on Our Food Problem is more essay than screed, a lyrical documentary that speaks to our common humanity. And The March almost got canned for alluding to Jim Crow and racial tensions in America. "It was probably one of the first truthful statements about race relations in America that the U.S. government would own up to," Richard Blue says.

James Blue may have had the potential to become one of the great American filmmakers, but he didn't have the inclination. Stints working for a New York ad agency and on a Hollywood film "drove him absolutely bananas," says Richard Blue. "He liked to have total control over whatever he was doing."

He left Hollywood for Houston in 1967. There he cofounded the Media Center at Rice University, which focused on teaching people from underprivileged communities how to tell their stories through film. This was a big deal. In the age of YouTube, GoPros, and iPhones, it can be hard to remember that moving images used to be the province of those with access to specialized equipment, money, and expertise.

Blue believed filmmakers had a responsibility to share their knowledge and access with people who were often ignored, Herskowitz says. The filmmaker also thought it was important for a film's subjects to have a say in its creation. His last project, The Invisible City (1979), took a surprising approach to investigating the poor neighborhoods of Houston. The Invisible City was a four-part program shown on public television. At the end of each segment, viewers were invited to call in with comments and leads, which were then incorporated into the next segment. "The films were evolving, with audience participation," Herskowitz says. "It was unprecedented."

Though participatory media is much easier to accomplish these days, Herskowitz thinks young filmmakers could learn a lot from Blue's approach. "He did not come to his projects as a kind of arrogant figure who knew ahead of time what he was going to say." He discovered the film's meaning as he went, "and really listened to his subjects and evolved the production with them."

Herskowitz became familiar with Blue's work in October 2012, when the website "Oregon Movies, A to Z," written by film historian Anne Richardson, published a brief article about Blue's accomplishments. (Filmmaker James Ivory '51, who had known Blue at the UO, alerted Richardson to Blue's work.) When Herskowitz read the article, he was "blown away." He had heard of Blue, but never knew he was so distinguished, nor that he had attended the UO. As he began researching the filmmaker, Herskowitz connected with Richard Blue, who was looking for a way to preserve and promote his brother's legacy. Together they tracked down copies of the films. They found a pristine print of A Few Notes on Our Food Problem, and even the parody of Hamlet James had made as an undergraduate at the UO. (It was in Richard's son's basement.)

Audiences are finally getting the opportunity to see these films as part of a six-month retrospective organized by Herskowitz, which started in November 2013 and continues through April. Panels on Blue's work will be part of the School of Journalism and Communication's "What is Documentary?" conference in April.

And scholars will finally have the opportunity to study Blue's artistic approach firsthand. Knight Library is acquiring James Blue's papers—90 boxes of material that James Fox, head of special collections and archives, calls "a national treasure." Once the papers are processed and available for research, Blue will be able to speak for himself about his artistic and professional decisions, Fox says.

More than 30 years after his death, James Blue's work is finally becoming known in a way it never has before—including here in the United States.

—By Suzanne E. W. Gray