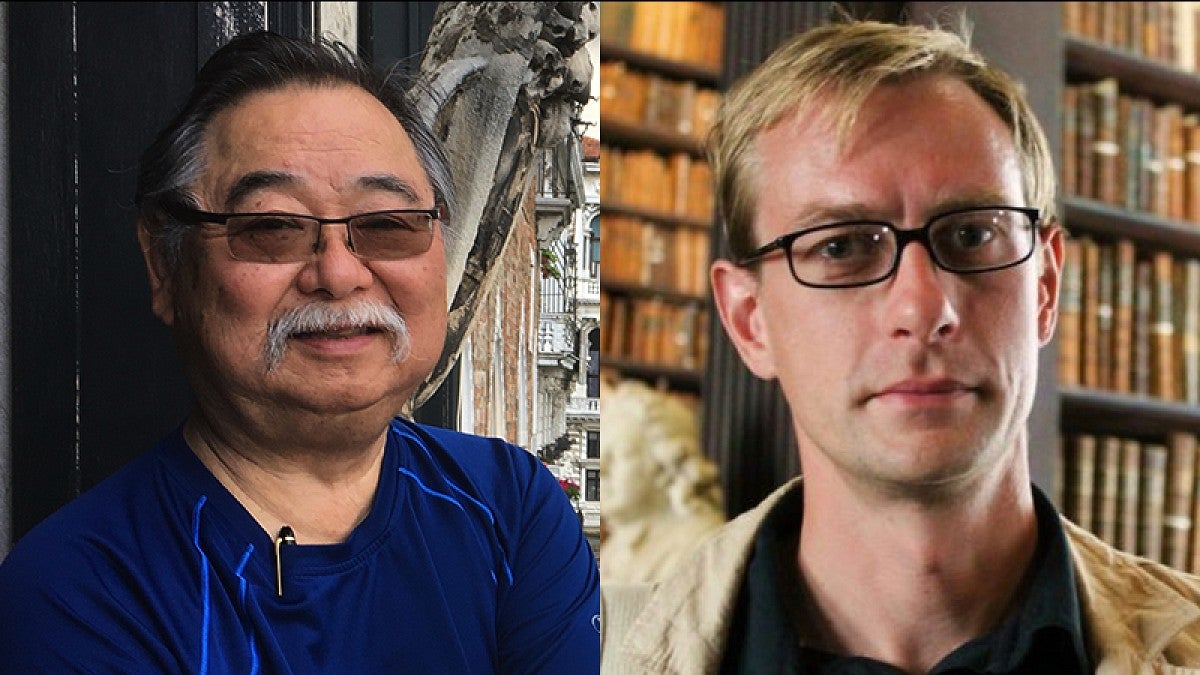

Two UO professors, a poet and a philosopher, have been named 2023 Presidential Fellows in Arts and Humanities in recognition of their distinguished record of scholarly and creative achievements and in support of ongoing projects.

UO President Karl Scholz bestowed the awards upon Garrett Hongo, Distinguished Professor in the Creative Writing Program, and Colin Koopman, professor of philosophy, in one of his first acts since taking office in July.

The award provides $25,000 in flexible funding that can be used for research or creative materials, travel, and other expenses and to for support time for scholarly and creative activity. Scholz will host an event in fall term to honor the two recipients, display and discuss their projects, and welcome colleagues and students from the arts and humanities community on campus.

Hongo, who has taught in the UO’s creative writing program since 1989, is an acclaimed poet and writer whose work has appeared in American Poetry Review, Antaeus, Field, Georgia Review, New England Review, Ploughshares, Parnassus, The New York Times, and The New Yorker. He was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for poetry for “The River of Heaven” in 1988.

His most recent book, “The Perfect Sound,” a memoir of his passion for and fascination with all things audio, was an Oregon Book Awards finalist for creative nonfiction. Hongo said the award will give him the freedom to travel and enjoy quiet periods of retreat and to “visit archives of historical material and interview some informants, and to be able to put my creative work foremost instead of it being back-seat so much of the time.”

He was in Paris when he got the news of the award, which made “for an extraordinarily buoyant day sauntering the avenues and boulevards,” he said.

“It’s very gratifying to receive this recognition for my recent work, in both poetry and prose,” he said. “I feel one of my most productive periods is ahead of me.”

He said the award increases his resolve to keep at his current project, still in the nascent stages: a multigenre work called “Nisei Bar & Grill” about three generations of Japanese-American artists and entertainers who gather in a Japantown bar in Los Angeles just before it is demolished.

Koopman, a member of the UO faculty since 2009, focuses his writing and teaching on the politics of information and the ethics of data. He is the author of “How We Became Our Data,” “Genealogy as Critique” and “Pragmatism as Transition.”

Koopman said he was grateful to receive the award and to see that work in the humanities on campus is being recognized and supported at the highest levels.

“In an increasingly technological society where so much emphasis is placed on efficiency and growth, one thing that the humanities can contribute is space and time for reflection on the consequences of what we are otherwise relentlessly pursuing,” he said.

The award, he said, will “afford me the most precious commodity for an academic: time.”

In an interview with The New York Times in March, Koopman said, “Data has become something that is increasingly inescapable and certainly inescapable in the sense of being obligatory for your average person living out their life.” This cradle-to-grave data immersion poses urgent ethical and political questions, he said, including how data entrenches and reproduces social inequities, and how such data inequalities can be lessened.

“We are awash in data: financial data, medical records, location data, browsing histories, private correspondence, and uncountably many data derivatives packaged together by firms ranging from mega-capitalized corporations like Amazon to data brokers like Acxiom who warehouse data on millions of people who have never even heard of them,” he wrote in his proposal.

Koopman said he plans to use the award funding to support research on a book on data equality to be titled “Data Equals,” which will explore how data technologies can be redesigned in ways that foster democratic equality by, for instance, combating political polarization and algorithmic discrimination.

—By Tim Christie, University Communications