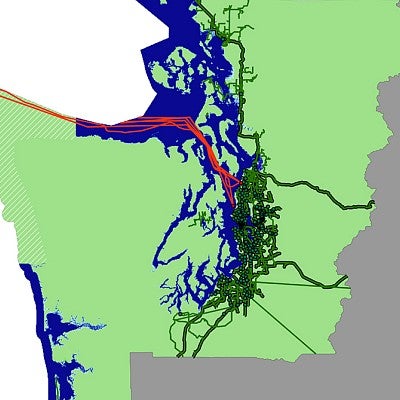

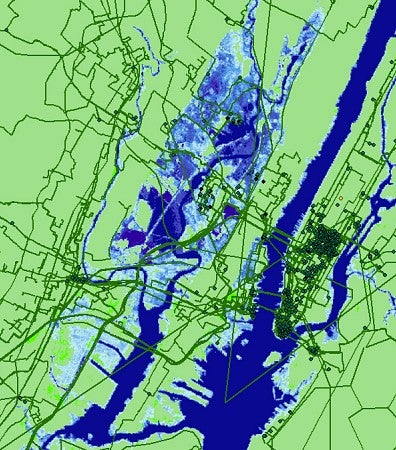

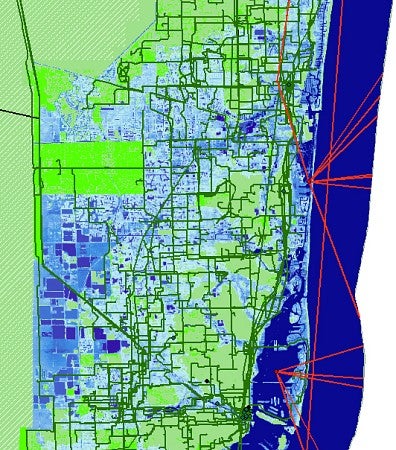

Rising seas threaten more than 4,000 miles of buried fiber optic cables in densely populated U.S. coastal regions, with Seattle being one of three cities at most risk of internet disruptions, according to a UO scientist.

In a July 16 talk to internet network researchers in Montreal, Ramakrishnan Durairajan, an assistant professor in the Department of Computer and Information Science, warned that most of the damage could come in the next 15 years. Strategies to reduce potential problems should be considered sooner rather than later, he said.

“Our analysis is conservative in that we only looked at the static dataset of sea level rise and then overlapped that over the infrastructure to get an idea of risk,” Durairajan said. “Sea level rise can have other factors — a tsunami, a hurricane, coastal subduction zone earthquakes — all of which could provide additional stresses that could be catastrophic to infrastructure already at risk.”

By 2033, the study also found, that more than 1,100 internet traffic hubs will be surrounded by water. New York City and Miami are the other two most susceptible cities, but the impacts could ripple out and potentially disrupt global communications.

“Most of the damage that’s going to be done in the next 100 years will be done sooner than later,” said the study’s senior author Paul Barford, UW-Madison computer scientist who was Durairajan’s academic adviser. “That surprised us. The expectation was that we’d have 50 years to plan for it. We don’t have 50 years.”

The study, which only considered U.S. infrastructure, combined data from the Internet Atlas, a comprehensive global map of the internet’s physical structure, and projections of sea level incursion from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The findings were shared with academic and industry researchers at the Applied Networking Workshop, a meeting of the Association for Computing Machinery, the Internet Society and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

The roots of the danger emerged inadvertently during the internet’s rapid growth in the 1980s, said Durairajan, who joined the UO in September 2017 soon after earning his doctorate at UW-Madison. Neither a vision of a global grid nor planning for climate change was considered during the technology explosion.

“When commercialization of the internet happened, everybody wanted to make money,” he said. “Companies started their own infrastructure deployments. Everyone had their own policies and deployed everything that they wanted in ways that were good for them.”

Conduits at most risk are already close to sea level. Only a slight rise in ocean levels due to melting polar ice and thermal expansion will be needed to expose buried fiber optic cables to seawater, the study found. Hints of the problems to come, Barford and Durairajan noted, were service disruptions during catastrophic storm surges and flooding that accompanied hurricanes Sandy and Katrina.

Mitigation strategies are needed to strengthen the coastal infrastructure so that failures there do not become cascading failures that take out inland stations, Durairajan said. The effects of building seawalls, according to the study, are difficult to predict.

“The first instinct will be to harden the infrastructure,” Barford said. “But keeping the sea at bay is hard. We can probably buy a little time, but in the long run it’s just not going to be effective.”

The study also examined risks to buried assets of individual internet service providers, finding that Century Link, Inteliquent and AT&T are at highest risk.

Carol Barford, who directs UW-Madison’s Center for Sustainability in the Global Environment, also was a co-author of the study.

—By Jim Barlow, University Communications, and Terry Devitt, UW-Madison