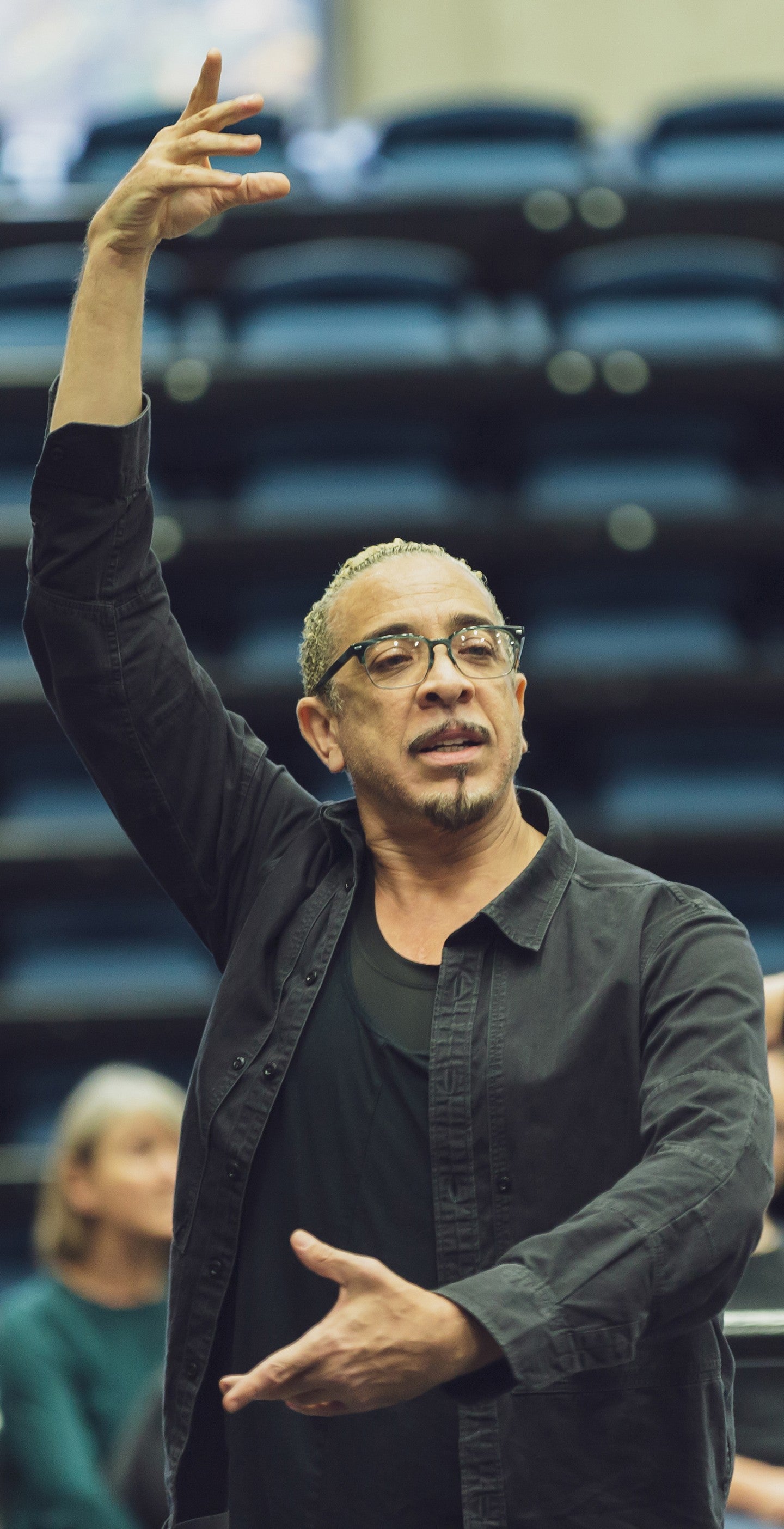

Dwight Rhoden is wearing black. Black shirt, black undershirt, black pants, black shoes, ankle-length black socks, horn-rimmed glasses with black frames. Even his neatly trimmed goatee is died black.

Just about the only thing about Rhoden that’s not black today is his hair, which is a fierce and unapologetically artificial shade of blonde.

It’s a fitting outfit for one of America’s most influential choreographers. His wardrobe choices are an echo of the dances he’s known for — stylish, singular and bold.

Today, Rhoden’s taken time out of his busy touring schedule to visit the School of Music and Dance, and share some valuable lessons from a life on stage with a roomful of UO dance students, as part of a master class co-sponsored by the Hult Center and the Eugene Ballet.

What’s happening sounds like a typical ballet class. Rhoden calls out familiar French vocabulary to a roomful of University of Oregon dance students working at the barre: plié, jeté, relevé, passé, chassé, tendu, fondu, port de bras and arabesque. But this is not your mother’s ballet.

“It’s a unique blend,” says Rhoden. “I think it’s really good for dancers today, who are actually going into the world of contemporary dance, because it integrates conventional ballet with elements of jazz, hip-hop — everything is in there.”

Some of the movements can be challenging, even for experienced dancers, says Sarah Ebert, an instructor in the Department of Dance.

“In the ballet world the spine tends to be quite erect, but (with Rhoden’s technique) there’s an integration of the center of the body, so there’s another ‘limb’ to think about,” she says. “The movements feel really creative and experimental.”

Rhoden is in perpetual motion as he glides around the room.

“You’re not just bending over and grabbing a table, you’re really sculpting out a curve,” he says, as he folds his body gracefully forward.

His feet tap. His hands clap. His fingers click.

He sings: “Wop, bop, be-bop.”

“You hear all this accompaniment I’m giving you?” he asks.

The students laugh. It’s a welcome relief from all that hard work at the barre.

Sabrina Madison-Cannon, the new dean of the School of Music and Dance, watches from the sidelines with a dancer’s eye. She started her own professional training at the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in New York, where Rhoden was once a star performer.

“He’s a very giving teacher,” says Madison-Cannon. “It was really nice to see how he taught our students with the same kind of passion and involvement that he would have taught professional dancers.”

Rhoden reaches up and gently grasps the foot of Jillian Davis, which is elegantly extended above her head at a seemingly impossible angle. She’s a dancer with Complexions Contemporary Ballet, here to demonstrate their unique technique.

He points out the correct positioning for the “IT band,” a muscle that runs the length of her thigh, as he rotates her leg slowly, like a living anatomy lesson.

“It’s inspiring to be with dancers who are that aware of their bodies and that under control,” says Lindsay Dreyer, a dance major in her junior year. “That control is just incredible to witness.”

Rhoden pauses briefly to take the pulse of the class.

“Yes? No? Maybe so?” he asks teasingly.

“OK. Other side.”

The class laughs again, as they turn to attempt a mirror-image of the rigorous warm-up, this time with the opposite sides of their bodies facing the barre.

Every word is chosen carefully, as Rhoden exhorts the students to keep up the effort.

“We have to do it. We have to do it. Every day, we have to do it.”

Rhythm, repetition, subtle evolution. A dancer’s sensibility.

“It’s not just physical stamina,” he says. “There’s another kind of stamina that’s involved in just getting through the exercises.”

Warm-up’s over. Now, it’s on to learning the choreography of a current work in progress.

Imagine you’re swimming a breast stroke, he tells the students, as he breaks down the complex choreography into simple movements.

“When people give you these images, use them,” he says.

It’s a demanding routine, but soon the class is dancing along with Davis, while Rhoden observes from the front of the room.

“He’s an amazing choreographer for a world-renowned company, and the fact that we got to work with them here in our studio is amazing,” says Olivia Oxholm, a senior double majoring in dance and public relations. “We’re so incredibly lucky and blessed to have that experience here.”

Rhoden asks the dancers to circle up for a few parting words of advice.

“Whatever (dance) experience you have a chance to be part of, just get all you can out of it,” he says.

He thanks the dancers. Then, he applauds for associate professor of dance Christian Cherry, who’s been accompanying the class with live music on grand piano and bongo drums. Finally, he turns to clap for dancer Jillian Davis, who responds with a slight bow.

Now, it’s the students turn to show their appreciation for Rhoden. They bend down and begin thumping the dance floor with their open palms. The noise rises, like that pivotal moment in a basketball game when it seems like the entire stadium is on their feet, stomping on the ground in unison.

Then the sound fades away. Class is over.

—By Steve Fyffe, School of Music and Dance