Not your parents' orientation?

It is at IntroDUCKtion

Not your parents' orientation?

It is at IntroDUCKtion

Not your parents' orientation?

It is at IntroDUCKtion

On a sunny morning in late July, parents drift into seats in the Straub Hall lecture hall. Kathryn Dailey, assistant director for Substance Abuse Prevention, asks if they’ve seen “Animal House,” the rowdy 1978 college comedy shot on the UO campus.

Lots of hands go up.

“I want to assure you that is not the UO experience,” she says. “The college experience is not drinking and partying and hooking up. A lot of students are not drinking.”

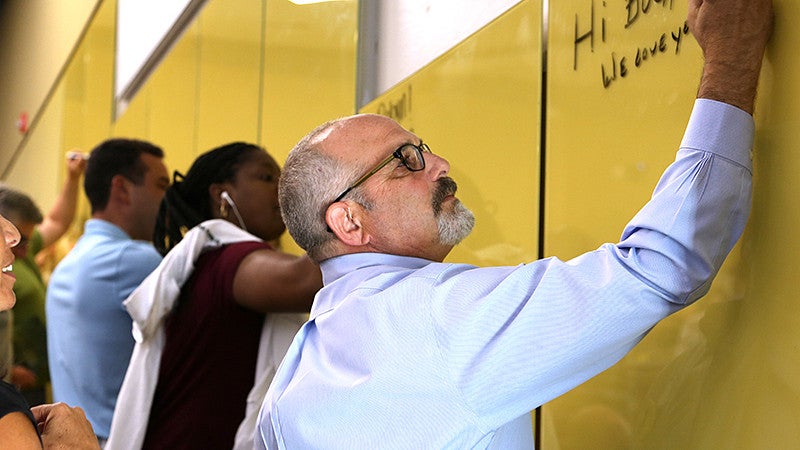

This is IntroDUCKtion, the two-day sessions that all new UO students attend, visits once known as orientation that now do much more than showing first-years where to find the dining hall. And it’s not just students who are being introduced to college life but also their parents.

The UO has transformed IntroDUCKtion and become a leader in helping students make the leap into campus living and helping parents let them do it. And the university has pioneered new programs aimed squarely at dispelling the myths about “party schools” and helping students stay safe and healthy.

During the visit, parents and family members attend sessions on topics that include money matters, how academics work at the UO and how to help their students succeed at college, something the staff call holding on while letting go.

But IntroDUCKtion goes beyond those college basics. Officials from student life and enrollment management have refined the way they communicate to parents and students, offering some straight talk about how to prevent sexual violence, binge drinking, and other unhealthy behaviors.

“It is important that we have conversations with our students and their families before they arrive on campus,” said Roger Thompson, vice president for enrollment management, “and talking about it from the very beginning sets the tone.”

It’s part of a comprehensive, science-based effort to keep new students healthy, safe, and successful as they make the transition from high school to college.

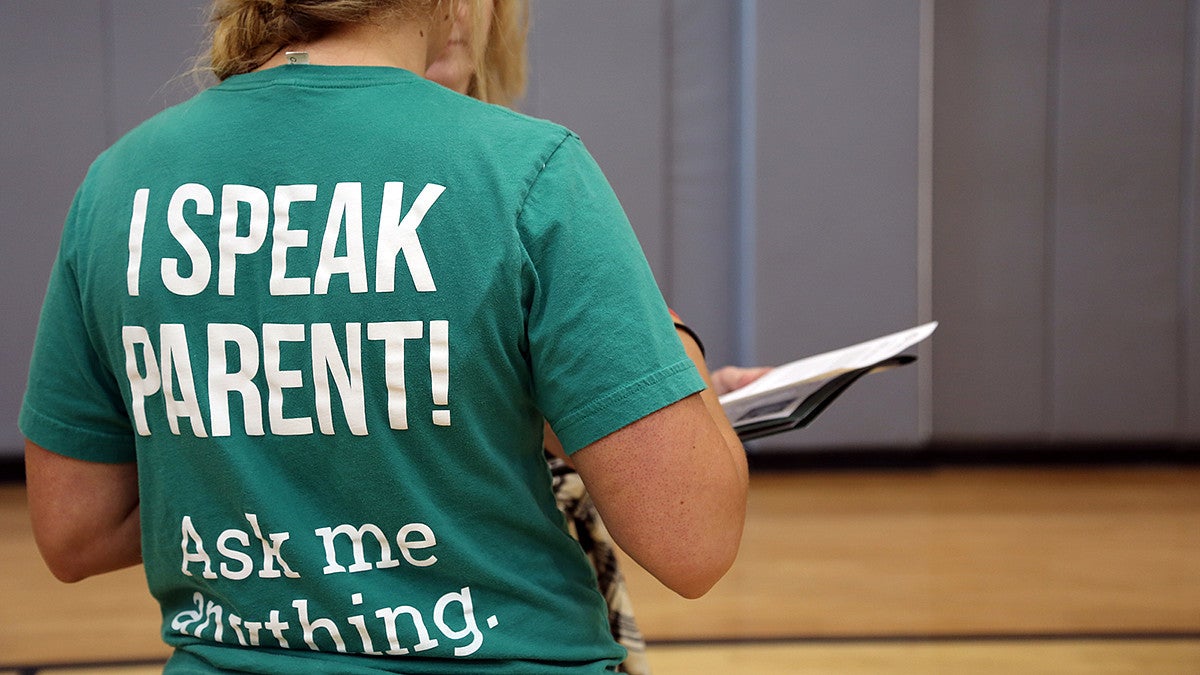

“It’s not just the academic transition,” said Erika Swanson, director of Parent and Family Programs. “It’s also the social transition. It’s how to encourage your student to connect with academic resources and student organizations but also to redefine the role parents play in their students’ success in higher education.”

The first six weeks of the academic year are a time when there is an increase in incidents of sexually assault and high-risk drinking on college campuses across the nation, according to several studies and surveys.

“We are asking students, most in their late teens, to not only go to school but also manage their own lives and finances and create a social support system in a very quick period of time,” Swanson said.

“There are multiple transitions at once. It’s a very dynamic time — they experience a lot of diversity, are faced with new choices and their value systems are being defined.”

Back in Straub Hall, Dailey is telling a roomful of parents that nearly one-third of incoming first-year students don’t drink and another 38 percent haven’t had a drink in the previous 30 days. And, she says, students will have no trouble finding lots of activities on campus that don’t involve alcohol.

The idea behind presenting such information is known as “social norming” — a concept holding that young people’s attitudes are often distorted by exaggerated depictions in media and culture and that those attitudes that can be changed by showing how young people actually behave, what the social reality actually is.

At the same session in Straub Hall, Kerry Frazee, director of sexual violence prevention, lays out the national numbers: One in 5 college women, and 1 in 16 college men, are victims of sexual assault.

She encourages parents to have conversations with their students even if they might seem uncomfortable. Ask them about consent; ask them if they know what their sexual boundaries are; ask them how they handle rejection.

Near the end of her talk, Frazee asks one last question: How many of you have sons? Hands go up. Frazee waits a beat and says, “Ninety-eight percent of perpetrators of sexual violence are men, which means 98 percent of perpetrators are someone’s son.”

Engage with your sons, she tells parents. Have the conversation. Help them change the culture.

“To just not have a conversation with their (male) students because, ‘Oh, it doesn’t affect them,’ is being ignorant,” Frazee says later, “and it’s a missed opportunity when their sons can be the leaders too. “

Those conversations may be awkward, but the investment is worth the discomfort, she said.

“The tip I have for parents is: Still communicate with your student,” she says. “Still set expectations about relationships, and about treating people with respect, even if you think your student is not listening, because they can still hear you. Your words mean so much.”

Jake Hodgin of Beaverton, father of an incoming student, said he was glad to hear university officials talking about how to help prevent sexual assault and binge drinking.

“I’m happy they are raising all these issues,” he said. “I’m glad they’re talking to students about that and putting it in their faces.”

University officials said the candid talk is intentional and reflects the national conversation about sexual violence on campus.

“Sexual violence is a national issue,” Frazee says. “I know it’s a real area of fear for our parents. It would be an even bigger area of fear if they didn’t know what the university was doing about it.”

But the idea is not to fan fears; rather, it’s to be proactive and to give parents and students tools, based on prevention science, on how to end and prevent sexual violence.

Frazee said she’s already seen the campus culture change around these behaviors.

“So many students are engaged and taking ownership of this issue,” she said.

Prevention science is an interdisciplinary field that tries to improve public health by identifying risky behaviors and protective factors, and determining which interventions can reduce risk and minimize harm.

“We want to make sure everything we do is grounded in research,” Frazee said, “because we don’t want to just throw programs out there hoping that our students are engaging. We want to know they’re going to be effective and create behavior change.”

One example: the Get Explicit program. Tailored for new students living in residence halls, the program addresses what it means to be a Duck by preventing sexual violence. Training includes interactive discussions about healthy sexuality, boundaries, communication, consent, alcohol, social norms, sexual assault, and bystander intervention.

“Our faculty are conducting cutting-edge research here at the UO,” said Robin Holmes, vice president for Student Life, “and their expertise and guidance truly enhances the effectiveness of our programs for students and their parents.”

Assistant professor Jessica Cronce said the overarching theme of her research in the Department of Counseling Psychology and Human Services is “exploring health and risk behaviors among college students.”

“This is really sort of the launching point for the rest of their life, so it is really pivotal that we help them have a successful launch,” she said.

She develops prevention programs for behaviors that can be hazardous to college students, including alcohol and marijuana use, gambling and risky sexual behavior. Working with the Division of Student Life is a natural partnership because they can help implement her programs, she said.

“It’s great for me to develop these interventions to help college students, but unless I have a way to deliver it to college students, it’s largely useless,” she said.

But intervention programs informed by prevention science are no magic bullet, she cautioned.

“It really is a community effort,” she said. “And it takes all of us to work together at this from various angles in order to keep Ducks healthy.”