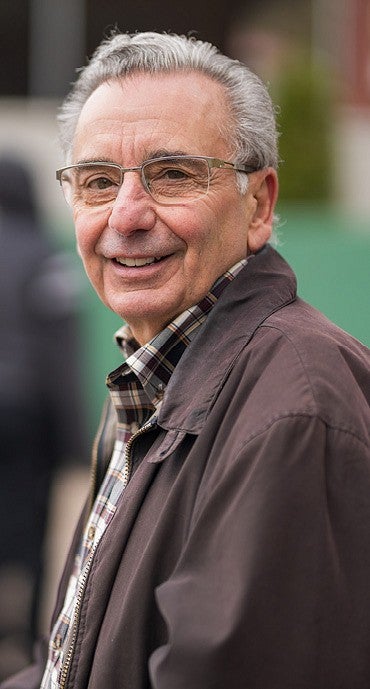

Like any good teacher, Greg Ahlijian encourages his students to ask questions. Sometimes those questions stay with him, as did a query from a young boy who once asked, “How did you overcome your fear of being here—you know, with us?”

It was a reasonable question. Ahlijian, BS ’71 (landscape architecture), is a volunteer instructor at Jasper Mountain, a comprehensive treatment center for emotionally disturbed children and their families. Located on a lush 90-acre campus outside Eugene, the center serves youth who have suffered severe trauma and abuse or exhibit antisocial and violent behavior, sexual issues, and other difficulties.

Ahlijian began volunteering at Jasper Mountain 12 years ago. On that day in 2018 when his student confronted him, Ahlijian answered in his usual calm and patient manner; he told him, “I never had any fear to be here with you. I feel very comfortable around you.”

RELATED LINKS

It’s intentional that Ahlijian does not know the histories of his students. “I’m not their therapist,” he says. “I want to have a relationship with each child in terms of what they show me.”

Each Thursday, when Ahlijian meets with his two classes, the students begin the session by reciting, “There is honor in meeting and overcoming life’s challenges.”

Ahlijian practices what he preaches—and it’s not reading, writing, or ’rithmetic. He designs his lesson plans around character development; his philosophy—for both his students and himself—is based on being honorable, engaging in self-discovery, and developing self-empowerment.

“These children had no control over the circumstances under which they were born or the environment they came into,” Ahlijian says. “What’s important is how they accept the challenges that life throws their way.”

Ahlijian’s assistance isn’t limited to his role as a teacher—he’s also raised substantial funds for the center and its youth.

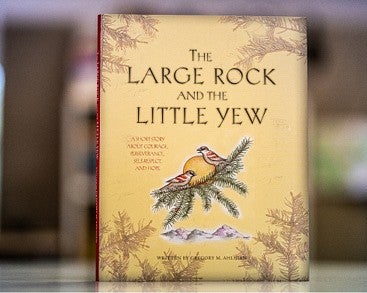

Inspired by his work with Jasper Mountain students, Ahlijian in 2010 self-published a short story called The Large Rock and the Little Yew. In this illustrated book, a yew tree seed struggles to grow from within the crevice of a rock. The rock discourages the seed and presents obstacles but the seed demonstrates courage, perseverance, self-respect, and hope as it ultimately becomes a yew tree.

Ahlijian has donated all proceeds—exceeding $112,000—to the center, funding a multiuse courtyard. Ahlijian contributed design elements, including a climbing wall, terraced steps, and large basalt columns engraved with virtues such as humility, pride, and faith. Proceeds also support the Gregory M. Ahlijian Scholarship Fund through the Oregon Community Foundation, for youth who have been in foster care or residential treatment in Oregon. The scholarship can be applied toward a four-year university, community college, or accredited trade school.

“Greg represents a model for others as an individual who has offered his unique talents to troubled and deserving children,” says Dave Ziegler, executive director of Jasper Mountain. “He is the first to say that of all he gives to the children, he receives so much more in return.”

Ahlijian and Little Yew are making an impact in other ways as well.

Beth Wheeler, an assistant professor in the School of Music and Dance who voluntarily runs a music program at Jasper Mountain, worked with students to write and perform a song based on the short story and another of Ahlijian’s books, Shine in Your Life’s Journey. They played the composition at Beall Concert Hall and, Wheeler says, continue to “work very hard to build a community in the music classroom.”

Also, the Eugene Ballet in February will stage a performance adapted from Little Yew, with students from the ballet academy teaming up with professional dancers. Josh Neckels, executive director of the ballet, was inspired to add a performance to the lineup after a friend of Ahlijian’s shared the book with him.

Ahlijian met with the choreographer and costume designer but didn’t offer many opinions. “My attitude was to just get out of the way,” he says. “Let them do their magic.”

While dance may not be Ahlijian’s forte, other art forms have sustained him—financially and creatively—throughout life.

“I never wanted a nine to five, Monday through Friday gig,” he says. “The only thing I could see myself doing that would provide that kind of freedom was being an artist.”

In his twenties, Ahlijian lived in an uninsulated barn in Eugene with no electricity or running water. He piled his abstract impressionist paintings into a beat-up truck and drove to Portland and Seattle, where he secured shows at galleries.

Later, Ahlijian worked as an arborist, drawing on skills he learned at the UO. He ran a one-man arboriculture business, diagnosing diseased trees, designing landscapes, pruning trees, and educating clients.

Throughout, he never forgot a promise he made to himself as a college student: “When I’m on my deathbed, I don’t want to look back and say ‘what if?’” he says. “I want to pursue my passions and not question why I didn’t do this or that.”

One of Ahlijian’s professors, the late John Gillham of landscape architecture, recognized his passion. He once told Ahlijian that if the country were at war and Ahlijian believed in the cause, there wasn’t anyone he would rather be next to on the frontlines. But if the country were at war and Ahlijian didn’t believe in the cause, there was no one from whom he’d want to be farther away.

“He seemed to have an understanding of me,” Ahlijian says with a chuckle.

Given Ahlijian’s commitment to a life of purpose and creativity, it’s not surprising that his retirement has been so fulfilling. “My experience at Jasper Mountain has been the most rewarding part of my life,” he says. “The children inspire me, they teach me, they give me purpose.”

Ahlijian had the center’s children in mind when he invented the yew seed character. But when the seed thinks to itself, “the greatest joy in life is found in small acts of kindness and giving,” it’s not hard to picture the author himself.

Kelsey Schagemann is a freelance writer and editor in Chicago.