In late 1914, a dead whale washed up on the Oregon coast near Florence. The locals went out to see it, then kept their distance to let time and the tides do their work.

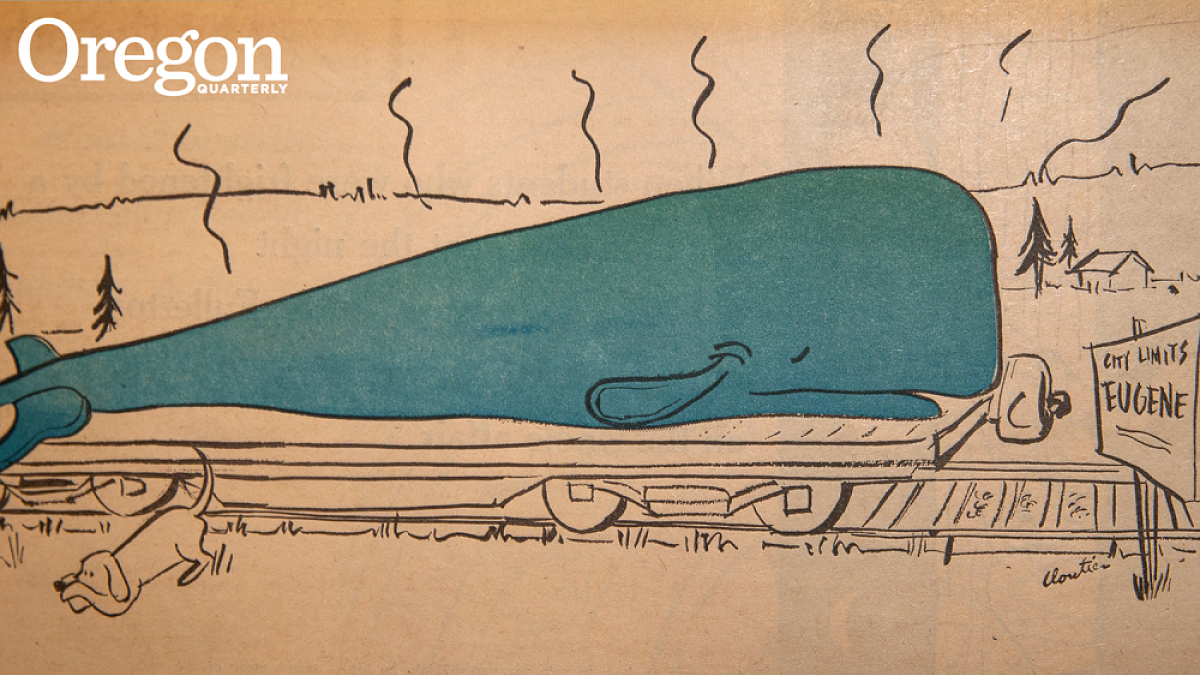

But one man had an idea. James Fullerton, of Eugene, decided the whale would make an excellent gift to the University of Oregon. He envisioned it being used for science classes, or making the skeleton into a frame for a small teahouse on campus. After the carcass had decayed for a few months, Fullerton and some volunteers cleaned it a bit, then had it loaded onto a train car and delivered one morning to the Eugene station at the foot of Skinner Butte.

However, Fullerton and his helpers hadn’t cleaned the bones completely, and the area surrounding the train station began to smell. Also, university officials had told Fullerton they had no accommodations for the skeleton, and had declined his offer. When the freight foreman called the railroad dispatch office for guidance, he was told he could keep the whale for himself. “I don’t want it,” he replied. “It stinks.”

So began a curious episode in the history of the UO—so curious that it filled the entire second issue of Old Oregon, the school’s nascent alumni magazine, in April 1919.

Fullerton felt the university officials hadn’t appreciated his efforts. He had worked his way across the country over the decades bridging the 19th and 20th centuries, and at age 65 he considered himself an entrepreneur and a champion of the common man, unafraid of authority or institutions. He spoke his mind, and in May 1917, he launched a monthly newspaper titled the Oregon Hornet, declaring that it would “sting everyone who tries to rob a taxpayer.”

It was mainly a platform for Fullerton’s opinions on business and politics—including diatribes against the university. He charged UO officials with graft, corruption, and more. He said the administration played favorites in awarding construction contracts, paid faculty “to teach girls how to hang curtains and other fancy stunts,” and turned a blind eye to rampant immorality among the student body. He claimed the school’s president, Prince Lucien Campbell, was unfit for office, calling him “a jelly fish [sic] with a broad yellow streak.”

Campbell and the university ignored the Hornet as much as possible. But after two years of monthly attacks, in early 1919 they charged Fullerton with libel. In court, they chose first to address the issue of student immorality, disproving Fullerton’s hearsay claims of trysts in canoes on the millrace, overnight trips to the woods, and visits to houses of ill repute. Then they presented the records on every complaint and rumor regarding student behavior from the school’s 40-year history, including stealing flowers and chickens, uttering profanity, and “Sabbath breaking, fist fighting and the like.” Dean John Straub testified that not one female student had ever “gone to the bad,” and no one had been disciplined for drunkenness in 10 years. The surprise was just how straight the students really were.

Fullerton was found guilty and sentenced to one year in jail, with 11 months suspended due to his age and frail health. The charges relating to corruption and graft were dismissed. The trial, wrote the editors of Old Oregon, “has brought to light a record of clean living and high thinking that no college or university, no lodge, no order, no church, can surpass and few can equal.”

And the whale? After a few days of newspaper stories packed with puns and clever comments, it was hauled outside of town and buried in an empty lot.

—By Steve McQuiddy

Steve McQuiddy, BA ’87 (English), MFA ’90 (creative writing), is the author of Here on the Edge (Oregon State University Press), a finalist for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize.