A free school lunch might be the one reliable meal each day for the kids of 3 million low-income US households. But is it even edible? Not always.

So says Sarah Stapleton, an assistant professor in the College of Education who studies food issues in schools.

Stapleton began her foray into food in schools through her dissertation work, in which she teamed up with teachers in a low-income Midwestern school district to explore the many ways food intersects with schools. Since joining the UO faculty, Stapleton has worked with local school-garden educators and school-food activists to continue researching food in schools.

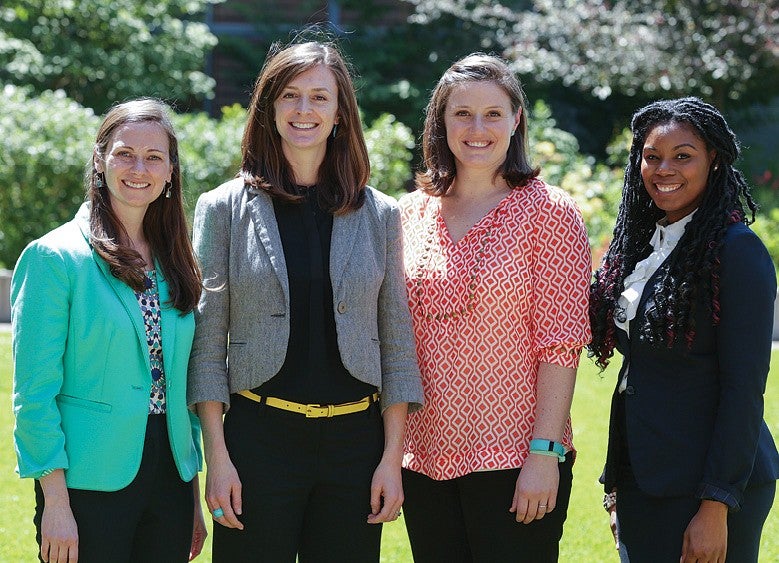

A nutritious school lunch is essential to the health and performance of our most vulnerable students, Stapleton says—in a new course, she teaches future educators (above) to critically assess what’s being served in the school cafeteria. “We must not be blind to our students’ most basic and important need: food,” she says.

Stapleton, of education studies, is one of several researchers in the college exploring our complicated relationship with food in contexts ranging from brain activity and exercise to preparing tomorrow’s teachers to help kids navigate food issues in schools.

Four recent hires in the college are zeroing in on obesity, which affects more than one-third of US adults and kids.

This team—Elizabeth Budd, Nicole Giuliani, Nichole Kelly, and Tasia Smith, all assistant professors—recently asked parents of children in Oregon grade schools to suggest ways the schools could encourage kids to eat better and exercise more. Most parents gave their schools high marks but said more should be done, according to Budd, who led the project. Improving nutrition standards for school meals and providing short physical activity breaks throughout the school day were the top recommendations.

Smith, who studies food in the community, has also worked with Kelly and Budd in the neighborhoods around these schools. Last year, she received a grant through the UO Office of the Vice President for Research and Innovation to examine how well a food access program is working in rural Oregon. The program is a partnership between Whole Foods Market and Oregon’s Oakridge community to improve access to healthy fruits and vegetables in rural areas.

Obesity is an extremely complex problem without a one-size-fits-all solution, Smith says. For some, healthier diets and more active lifestyles may be the answer; limited access to healthy food hinders the ability of some people to make healthy choices, while others aren’t motivated to exercise or don’t have the opportunity to do it regularly.

Another hurdle to healthy eating: food cravings. Giuliani, who studies the brain’s role in how we control those cravings, recently teamed up with Elliot Berkman, associate professor of psychology, to explore how the brain and emotions interact to regulate temptation. They concluded that cravings can be managed by turning our attentions elsewhere or focusing on the benefits of restraint, such as weight loss. The two also encouraged scholars and health experts to revisit the current thinking on cravings, with hopes of uncovering new strategies for managing them.

Giuliani is currently investigating how parents help cultivate these regulatory skills in their young children, through direct instruction and supportive parenting.

Kelly, a specialist in obesity and eating behavior, also studies the role of the brain in food issues. Specifically, she’s trying to determine whether overeating is associated with the ways we make decisions and manage our behaviors—our so-called “executive functioning.”

She’s found that kids who perform poorly on tasks measuring executive functioning sometimes eat more when given access to a large lunch buffet. Now she’s working with Oregon elementary schools to improve kids’ daily eating habits; reorganizing the timing and structure of recess, for example, might enable kids to make better decisions at lunchtime.

Kelly also studies loss-of-control or binge eating, which is associated with obesity, depression, and eating disorders.

Working with Smith, Budd, Giuliani, and others, Kelly recently delved into a little-researched area, examining loss-of-control eating in young men who identify as African American, Hispanic-Latino and Asian-Asian American. The results suggest loss-of-control eating could help explain known associations between perceived discrimination and heightened risk for obesity and chronic diseases in some racial-ethnic groups.

Also, Kelly says, “finding ways of helping young men strengthen and explore their ethnic identity may help their health and well-being, including their eating behaviors.”

Budd, meanwhile, dissects the problems of obesity and poor health through one of the remedies—physical activity. She has examined community factors that influence adolescent girls’ enjoyment for physical activity and she teaches a course on public health problems facing both the United States and the world.

For Stapleton, who prepares future teachers to be successful, school food isn’t just a question of health, it’s also a social justice issue.

Her new course, “Food and Schools,” which covers topics such as agriculture, school gardens, and school food waste, also delves into student hunger and the importance of ethnically sensitive meals.

Says Stapleton: “The course broadly focuses on food issues within schools and helps future educators see how their roles can and should connect to food in a myriad of ways.”

In underscoring the importance of community partners to healthy school food, Stapleton coordinates guest speakers and field trips through local organizations that oversee school gardens, emergency food relief, and farm-to-school programs.

She places her students with schools and community groups for fieldwork, enabling them to see the application of topics presented in the classroom. Students help teach school-garden classes, volunteer in school kitchens, and monitor school meals.

In March, the class visited a farm owned and operated by the Bethel school district in northwest Eugene. Students toured farm fields, gardens, a barn, and a greenhouse, while learning how the farm links both to curricula and school cafeterias within the district.

Stapleton wants more from her teachers-in-training than just an understanding of school food issues. She also wants them to make change—students must develop actual projects to address the problems about which they are learning.

The importance of the work being done in the food and schools class isn’t lost on student Tessa Karbum, of UOTeach, the master’s program for teacher licensure preparation.

School food “is a hugely political issue and deeply affects both the students we teach and their ability to learn,” she says. “The food we choose to serve and how we serve it not only effects our children but our local community and the health of our planet.”

—By Matt Cooper, University Communications