If you know anyone who belongs to a union or who has sought remedy for a personal injury through the courts, they’re benefitting from the legacy of University of Oregon graduate James Landye.

He was, in the words of Senator Wayne Morse, “the most brilliant student in the history” of the UO School of Law.

Irish by ancestry but born in Wales, Landye met Morse in 1931 when he was a 20-year-old first-year law student from Portland. Morse, at 31, was the youngest law dean in the nation. They formed a lifelong bond stemming from a shared passion for workers’ rights in an era when trade unions were still forming and the field of labor law was in its infancy.

Morse and Landye would support each other’s efforts in many ways over the years, professionally and as best friends. When Landye married his UO sweetheart, Ethel Mason, BA ’31, he asked Morse to be his best man. When his own interests shifted to politics, Morse asked Landye to help manage his campaign for the US Senate.

In 1934, Landye celebrated graduating first in his law school class by visiting family in Wales and South Africa. On his return, he hired on as one of two attorneys with the San Francisco-based Pacific Coast Labor Bureau in 1935. He would hopscotch the Pacific Northwest representing a host of young unions—from striking loggers to shipyard workers—in strike negotiations and at hearings before the newly formed National Labor Relations Board.

He worked nonstop. Ethel, who died in 1996, wrote about the toll that dealing with the “vitriolic” labor disputes of the 1930s took on her husband:

“Jim was hopping mad about the way management was treating labor, but at the same time he was very much opposed to the use of violence to settle labor disputes. So while he remained calm on the outside during these battles, he churned on the inside.”

By 1938, Landye was in private practice with B. A. Green in Portland. He began fighting to overturn an Oregon law banning picketing on the grounds that it abridged free speech and a free press and was a violation of the Oregon and US constitutions. The case, filed on behalf of the Teamsters, the AFL, and the railroad brotherhoods, went all the way to the Supreme Court of Oregon, which overturned a lower court’s ruling and struck down the statute as unconstitutional in 1940.

During that time, Landye also helped secure a steady flow of lumber for the war effort. His reputation as an ethical, trusted advocate for labor had resulted in his appointment to the West Coast Lumber Commission of the War Labor Board.

“Under Jim’s steady hand, crisis after crisis in the lumber camps in the Northwest was resolved,” wrote George Bodle, a Los Angeles attorney who had worked with Landye at the labor bureau. “It is no exaggeration to say that the maintenance of peaceful labor relations and full production in the lumber industry during World War II was primarily the achievement of Jim Landye.”

But by December 1943, Landye needed immediate treatment for ulcers, and he resigned from the commission. Morse had warned him to ease off a few months earlier, to no avail.

“In many respects we are peas out of the same pod,” he wrote Landye in February 1943. “However, take it from me, I have learned how to let down, and I am sure that had I not learned that lesson I would have been a physical wreck long before this.”

However, aside from time with his children and the occasional fishing trip, Landye didn’t let down. While maintaining a private practice in Portland, he continued to defend unions and became famous for winning cases on behalf of workers who were injured, maimed, or disabled on the job. “Some of the largest verdicts obtained in Oregon were the result of his work,” Bodle wrote.

In 1946, Landye helped set in place and became the second national president of an organization that continues to define best practices for attorneys—the National Association of Claimants’ Compensation Attorneys, now known as the American Association for Justice.

In 1947, he became the first labor lawyer elected president of the Multnomah Bar Association and in 1949, was elected to the Oregon State Bar’s prestigious Board of Governors.

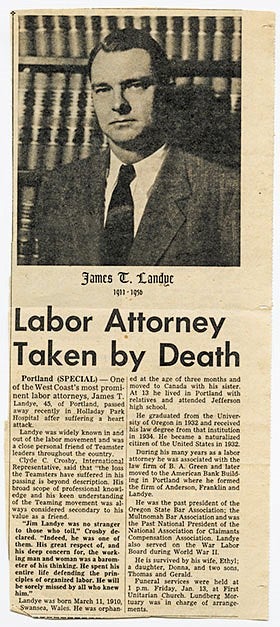

Landye died suddenly of a heart attack in 1956, just as his friend Morse was facing the nation’s hottest senate race against Douglas McKay. He was only 45, and while six decades have passed since then, his contributions remain indelibly woven into the practice of law and Oregon history.

A Life of Service

1. Incredible journey

Landye was born March 11, 1910, in Swansea, Wales, and orphaned at three months. His 15-year-old sister May, traveling on her own, took him and their six-year-old sister Hannah to Silverton, a mining town in British Columbia, where an aunt had agreed to take them in.

2. Dishwasher at 6, miner at 12, union organizer at 15

It’s easy to see why Jim’s heart was with working people. At six, he earned meals by washing dishes at a hotel. At 12, he worked nights driving a six-horse team pulling ore-filled wagons to the smelter. When his aunt died, he and Hannah moved near May and her husband in Portland. Self-supporting from age 13, he worked as a union-represented mailer for the Oregonian and the Oregon Journal while going to school. At 15, he organized the press operators into the guild, leading them on a strike for improved working conditions.

3. Family man

Landye met and fell in love with Reed College transfer Ethel Mason, BA ’31, while both were UO students. After graduating, she took her first teaching job in Klamath Falls, making the drive back to Eugene every weekend to see Jim. They married in 1935 and had three children: Donna, Tom, and Jerry.

4. Sudden death

After nominating the new slate of officers for the Multnomah Bar late in the evening on January 10, 1956, Landye suffered a severe heart attack. He was rushed to the hospital but died almost immediately. Three days later, the largest funeral ever at held at First Unitarian in Portland saw men standing along the walls and packed into the church lobby. Active pallbearers included Senator Wayne Morse, the CIO president, and four of Landye’s law partners. Among the additional 40 honorary pallbearers: five Oregon Supreme Court justices and six Circuit Court justices. Both of the state’s highest courts closed for the day in Landye’s honor.

5. UO’s James T. Landye Scholarship

Ten days after Landye died, the Sidney Hillman Foundation, named for the founding president of the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union, honored Morse with its $1,000 award for meritorious public service. He promptly assigned the entire prize to a trust created to fund scholarships in Landye’s memory. Several of Landye’s closest friends stepped up as trustees: E. B. MacNaughton, president of the Oregonian Publishing Company and First National Bank; J. D. McDonald, state president of the AFL-CIO; Kenneth J. O’Connell, a UO law professor and former Oregon Supreme Court chief justice; Ben Anderson, one of Landye’s law partners and a state representative; David C. Shaw, a UO law professor; and Robert Mautz, BL ’28, partner in the firm that is now Schwabe, Williamson & Wyatt.

In 1993, Landye’s son Tom organized transfer of the privately managed endowment to the UO Foundation and contributed additional funds so the annual awards would meet the present-day needs of law students. He and his wife Pat also have made a gift in their estate that they hope will eventually support full rides for Landye Scholars. “I think this is what my dad would want,” he says.

—By Melody Ward Leslie, University Communications