When a colleague asked Darin Stringer to participate in a reforestation project in Lebanon, he agreed right away. The founder of Pacific Stewardship, a forestry consulting firm in Bend, thought they were talking about Lebanon, Oregon.

“And then the guy said something about Beirut and asked if I had an up-to-date passport,” Stringer recalls with a chuckle.

At first, Stringer was daunted by the idea of applying forestry practices in a country perhaps best known to Americans as a war zone. It took some convincing to assure his family that he would be safe in the region. But Stringer decided that he wanted to lend his expertise in a country where the science of forestry is a foreign concept.

Stringer, who majored in political science at the University of Oregon and earned a master’s in forestry at Oregon State University, has a predilection for finding the middle way. He was an undergraduate at the height of the spotted owl controversy, and even then, he says, he was more interested in making forestry practices more sustainable—both ecologically and economically—than in taking an extreme position on either side of the debate. He drew on that background as he began to ponder how his experiences in the forests of Oregon and Washington could be applied to a strikingly different landscape.

Stringer has now made several trips to the small Middle Eastern country, which is so dry and rocky that locals are understandably skeptical that growing forests there is even a possibility. With support from the European Union, the World Bank, The US Forest Service (USFS), and the US Agency for International Development (USAID), millions of trees are taking root. It now seems conceivable that Lebanon may one day have great forests again.

A Legacy of Trees

Centuries ago, lush forests covered much of what is now Lebanon. It’s hard to believe now, observing the barren landscape that is more desert than wood. History and literature, however, tell another story.

Documents from the early days of Egypt and Mesopotamia (as far back as 2600 BCE) are filled with notations related to valuable timber from the region. A Phoenician account from the third millennium BCE describes “a vast forest whose branches hide the sky.” Biblical references to cedars from the region abound. The Epic of Gilgamesh, from the second millennium BCE, includes this passage:

“When they had come down from the mountain, Gilgamesh seized the axe in his hand: he felled the cedar. When Humbaba heard the noise far off, he was enraged; he cried out, ‘Who is this that has violated my woods and cut down my cedar?’”

Since Humbaba’s time, the violators have been legion.

Solomon’s temple was built from wood harvested in Lebanon. So were ships, temples, and crypts of Egyptian pharaohs. Massive bas-reliefs from the palace of Sargon II (722–705 BCE) depict trees being chopped down and transported all the way to the Euphrates River. The list goes on.

The people of Lebanon have depended on wood fires for heat and cooking for centuries. Humans have cleared these forests for hundreds of years, and the resulting expanse of sandy soil dotted with a few trees and scrubby shrubs is testament to just how much humans can alter a landscape. Given the rocky soil and the dry climate, attempts to reforest the country have failed.

Until, maybe, now.

New Growth

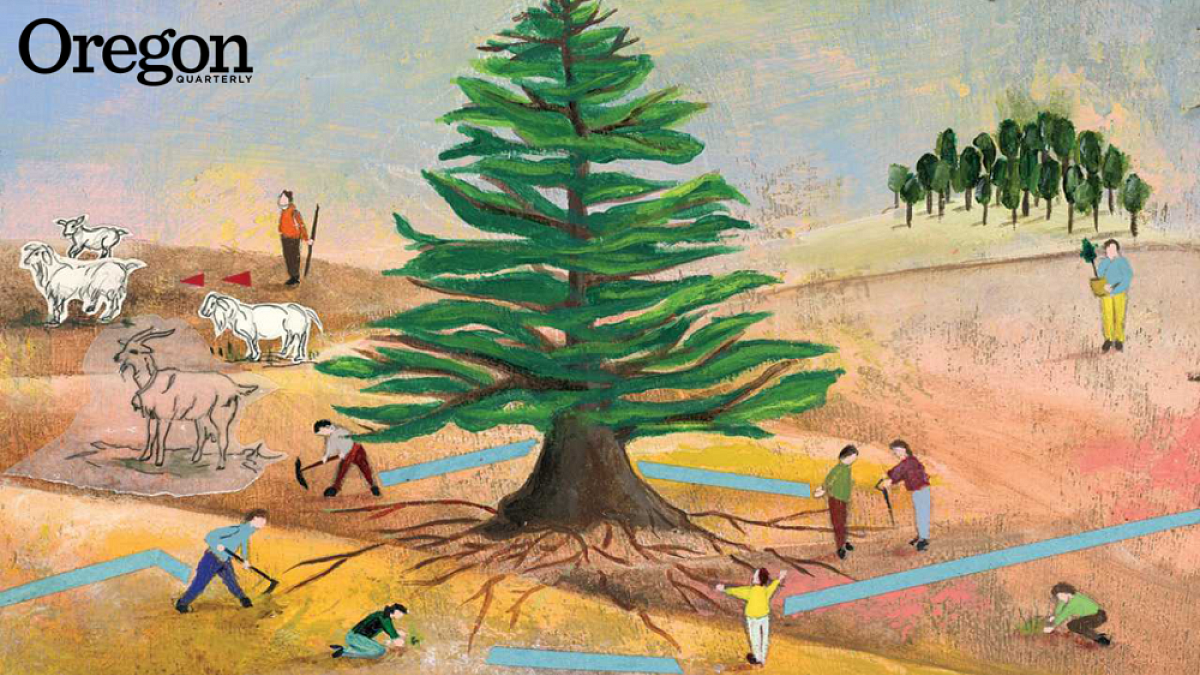

Stringer has joined the Lebanon Reforestation Initiative (LRI), an effort sponsored by USAID and the USFS that is taking reforestation techniques developed in the Pacific Northwest and adapting them to the conditions in Lebanon. In partnership with local residents—including farmers, recent college graduates, and even goat herders—Stringer and his colleagues are making progress in bringing significant numbers of new trees back to Lebanon.

Those involved with LRI hope that reforestation will encourage increased biodiversity in Lebanon. Trees, of course, can offer many benefits, ranging from shade and reduced erosion to the capture of carbon dioxide and creation of potential cash crops—like pine nuts—for local farmers. Beyond establishing tree nurseries and forest-planning programs, LRI is also working to reduce the risk of wildfires. Stringer hopes that the current project will help establish an enduring approach to forestry in Lebanon.

“The extreme challenges of reforesting Lebanon demonstrate that good stewardship of forest ecosystems is wiser and more cost-effective than trying to restore a forest after heavy exploitation,” he says.

According to a recent report, half a million trees have been planted in project sites over the past three years. The seedlings, all native species, include the cedar that is so closely associated with Lebanon—the tree that appears on the country’s flag—but also juniper, pine, oak, and others. So far, the project has covered 1,500 acres, and that is only the beginning. For the coming year, a million seedlings are growing as part of a long-term initiative that could eventually lead to the planting of 40 million trees.

This is a lofty goal for areas of the country where, as Stringer puts it, it is not evident that trees ever grew. As of 2005, only 13 percent of the country was forested—a 35 percent decline in 40 years. Given the progress so far, Stringer is cautiously optimistic the trend can be reversed.

“When you plant a seedling, there is a strong chance that it won’t survive unless you make all the right moves,” he says. “But we believe our efforts are making a positive difference.”

A big difference, as it turns out.

According to Chris Soriano of the USFS International Programs office, in past reforestation efforts in Lebanon, one-year survival rates were only about 25 percent. The current effort has yielded survival rates of about 80 percent. Soriano believes the project has great potential for future success.

It Takes a Village

So why has this project seen success, while others haven’t? It’s complicated. Stringer and his LRI colleagues have provided training, follow-up, and equipment that were not available before. But in large part, the success is due to slow and deliberate efforts to build community around a common goal.

“The key to our success is citizens who are passionate about bringing back forests,” says Stringer. “What’s going to make the difference is the local farmers who plant and monitor the trees. So it is important for us to provide training and tools that work within the established culture.”

Soriano agrees. He notes that the Lebanon effort has been particularly successful in linking the latest science with the particular needs of the local region. While the US Forest Service has active programs in about 70 countries, this is one of the few that is focusing on growing new forests rather than preventing illegal logging or similar defensive measures, he says.

The LRI program sponsors nurseries where seedlings are grown and provides education in proper planting techniques. Stringer and colleagues have also trained recent Lebanese university graduates with backgrounds in science or engineering to monitor the planting, making sure that proper techniques are followed and any mistakes—like seedlings that are not planted deep enough in the ground, or that are planted too close to rocks—are quickly corrected. They have also developed new planting tools, made by welding together existing picks and hoes, so that volunteers have effective equipment made from familiar parts.

“We tried having them use hoedads,” says Stringer, referring to a tree-planting tool popular in the Pacific Northwest. “But it’s difficult in extremely rocky soils, very expensive to import those from the US, and a hoedad has limited use to a farmer in Lebanon. By creating a tool that is similar to what the farmers use in their daily work, the tool becomes much more utilitarian and appealing.”

Trickier still has been to get farmers to follow sustainable irrigation practices based on those Stringer has used in the Pacific Northwest.

“The farmers are so used to irrigating everything they grow with systems of tanks and surface-level hoses, it is hard to convince them that with high-quality trees, good planting and maintenance practices, irrigation is not always necessary,” says Stringer.

One alternative is underground irrigation systems wherein small amounts of water are delivered to the root systems of trees through buried PVC pipes. Each tree receives a few liters of water during the critical first year, and then the pipes can be unearthed and used in another location. Stringer says that the ultimate goal is to understand what conditions require irrigation and then apply systems that are cost-effective and use minimal amounts of water.

Culture, as well as nature, can work against the project taking root. For those who raise goats, reforestation seems like an imposition, requiring them to change long-established travel patterns in order to protect trees. This can be a tough sell, but a necessary one.

“Goats can destroy trees at any stage of their lives,” says Stringer. “Young trees are most at risk, but goats can even kill adult trees by stripping the bark. It’s been critically important for us to communicate with shepherds about the benefits of these trees and to gain their cooperation.”

One of the most important successes of the program thus far is that it has brought together people of different faiths and disparate interests to work together on reforestation.

“It’s amazing to see communities with different religious and cultural values coming together to share ideas on how to restore their forests,” says Stringer. He notes that he and colleagues have collaborated with Christian, Druze, Shia, Sunni, and mixed communities.

“Restoring forests in such degraded and politically unstable areas is no small task. While the knowledge and practices we have brought to the project have been key, success really hinges on the Lebanese resolve to steward these plantings with a long-term vision.”

Navigating Danger

The daunting realities of reforestation in Lebanon go far beyond climate and soil conditions. Lebanon is also, of course, the site of significant political tensions and war. The small country shares borders with Israel and Syria and has long been considered of “strategic importance” by the US government.

When Stringer was first asked to participate in the LRI project, the US State Department was officially discouraging Americans from traveling to Lebanon. When he arrived in the Beirut airport for the first time, Stringer discovered fellow travelers gathered around a television, watching news coverage of a bomb blast. He assumed the report was from Iraq, but he soon found out that the explosion was less than mile from his current location. Shortly after he made his way to his lodgings, he learned that the airport had been closed for security reasons.

“I really don’t want to paint a picture of Lebanon as a dangerous place,” Stringer says during a telephone interview from his office in Bend. “I always felt safe during my five trips there. We had a driver and could travel freely around most of the country. But all the Americans, and the Lebanese we work closely with, take precautions. We don’t stay in one location for very long, and generally we keep a low profile. We are careful about those things.”

Sometimes in the course of his work in Lebanon, however, Stringer could not help but be reminded of the country’s predicament. One of LRI’s most successful plant sites is a former minefield. The location has been cleared of explosives, but Stringer reports that he still finds himself jumping from rock to rock, just in case.

“One of the reasons that location has thrived is that nobody wants to take their goats through a minefield,” he says.

Another of the LRI planting sites is less than half a mile from the Syrian border, and he has seen Syrian soldiers watching him work from a distance.

“The border is fairly porous and poorly delineated in some of the areas where we are working,” he says. “On one occasion we were told we were too close to the border and needed to leave the area immediately”

“At the same time, the people of Lebanon have generally been very friendly,” he says. “We feel like we have made good strides and gotten a lot of people interested in the project. The difficult thing is that everything needs to go right in order for these trees to survive.”

For the time being, many trees are surviving, and the Lebanon project is inspiring similar efforts in countries elsewhere. A delegation from Armenia recently traveled to Lebanon to study the growing techniques used there. Stringer believes that the techniques used in Lebanon are applicable to any areas where ecosystem degradation and a drying climate present serious challenges to reestablishing forests.

“The Lebanon project drew on the latest science, and it benefitted from experts, like Darin, who brought a wealth of experience,” says Soriano, of the Forest Service. “But Darin recognized that the local community has a lot of knowledge to contribute and that they are the ones who will ultimately determine the success of the project. I am very hopeful that with the planting protocol we have put in place and with effective monitoring techniques, that reforestation efforts will continue long after our project is over.”

—By Jonathan Graham

Jonathan Graham is the former managing editor of Oregon Quarterly.