Shortly after finishing her finals, University of Oregon senior Michi Yasui applied to attend graduation with her class on May 31, 1942. The commencement ceremony would begin at 8:00 p.m. at McArthur Court. But the United States was at war with Japan, and under internment policies, Japanese American students were confined to their dorm rooms by a strict curfew. Though the university had petitioned the government on her behalf, Yasui was no exception. She was denied permission to attend her graduation ceremony.

Yasui’s story is well-documented; she was one victim of many during a time of heightened national fear. But English major Alec Cowan added insight to previous accounts by examining the experience of many Japanese American students at a time when anti-Asian sentiment ran high and the study of English was a pivotal wartime tool.

In 2017, toward the end of his junior year, Cowan, BA ’18, joined an ambitious project: writing a history of the English department by researching Special Collections and University Archives, a repository of original documents dating back to the university’s founding. The project was developed by John Gage, director of the Center for Teaching Writing, and Corbett Upton, associate director of undergraduate studies. They saw an opportunity to document department history while helping undergraduates develop research skills.

Cowan, who transferred from Colorado Mesa University to pursue an English degree, focused on World War II. He had worked as a columnist, reporter, and podcast editor for the Oregon Daily Emerald and brought this experience to bear, layering research he discovered in special collections with other sources: a transcript of a radio speech from the archives; National Japanese American Student Relocation Council (NJASRC) records; testimonials and statistics from other universities; and newspaper clippings from the Emerald. “There’s this old adage that journalism is the rough draft of history,” says Cowan. “It was cool to see that the school newspaper covered issues that weren’t covered in detail anywhere else. I would find these clippings and think, ‘Oh, a typical news day report,’ but for such a monumental research situation, it was invaluable.”

Cowan’s paper, “English as Weapon, English as Sanctuary,” shows how English was utilized as communication during the war effort and as a tool that Japanese Americans used to help get them to safety.

In a 1943 radio speech, Clarence Valentine Boyer, then chairman of the department, made a passionate, bombastic defense of the necessity of English for the war effort: “The great importance of training in English composition lies in the fact that writing is one of the chief means of communication, and communication, at all times essential to civilization, has become an invaluable weapon to the successful prosecution of the war.”

Boyer cited the necessity of every serviceman to possess literacy, accurate expression, and the ability to understand “explanations concerning complicated movements and machines.” According to Cowan, the speech “featured quotes from Mill, Milton, Cowper, Burns, and Shakespeare throughout. A defense of country needed a defense of English.”

But for the “Nisei”—Americans of Japanese descent—command of English was essential for a different kind of defense: defense of citizenship.

At the UO, Japanese American students hoping to counter anti-Asian sentiment expressed their patriotism through letters to the Emerald, Cowan found. In records of the NJASRC, a resettlement organization for college students and internment inmates, he discovered that by 1943, 1,600 Japanese American students from West Coast schools had transferred to schools outside the exclusion zone. Most—28 percent—were liberal-arts students.

A command of English made a strong case for transfer, Cowan says. “Before the war, the study was an academic enterprise—but now, it was an asset in the defense of basic freedom,” he writes. Testimonials from transfer universities praised students who were both patriotic and proficient at speaking English. “One of the girls wrote an English theme on ‘What We Americans Will Do to Those Japanese’ and read it in English class,” wrote one dean. “Any other Nisei of this type would be welcome to come to school here.”

The largest exodus of UO students was to Colorado, and Yasui was in this number. On the same night as her graduation ceremony, Yasui fled Eugene by bus, knowing it was the only way to avoid incarceration in an internment camp.

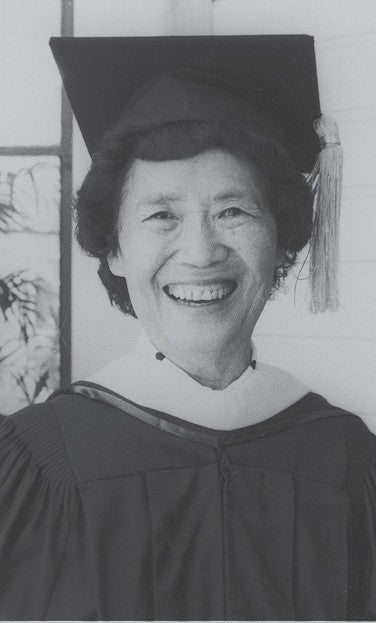

In 1986, four decades after the fact and at the invitation of university officials, she attended her commencement ceremony at Hayward Field. Her remarks prompted a standing ovation as local, national, and international TV cameras rolled. Former UO president Meredith Wilson, who also spoke, would later remark, “What a beautiful way to be outshone.” Yasui Ando died in 2006.

The end of World War II didn’t necessarily mean a welcoming back of Japanese Americans to Oregon, Cowan learned. He cites “No Japs Allowed” signs prominently placed in businesses, and Oregon’s former governor and congressman Walter Pierce is quoted as saying, “We should never be satisfied until every last Jap has been run out of [the] United States and our Constitution changed so they can never get back.” Even the Emerald ran skeptical columns on the allegiances of the newly returned students. “I think it’s interesting to revitalize and give life to history, especially areas that are dark and hard to acknowledge,” says Cowan.

Gage says Cowan expertly navigated the vast records in special collections, deriving “a meaningful story and a significant contribution to history from all this raw material.”

Cowan’s research on English continues. He is currently working on part three: how the study of English changed, following World War II and the GI Bill, to accommodate an influx of veterans. English, says Cowan, is more than just an academic study. It is fundamental to who we are; for someone like Yasui, it was a lifeline.

“The study of English creates this kind of national consciousness,” says Cowan. “The way we write, the things that we write, define who we are as a country, for better or for worse.”

—By Tara Rae Miner

Tara Rae Miner, BA ’96 (English), is a freelance writer and editor in Portland.