A friend and I pulled into Walla Walla, Washington, on a rain-brightened Friday afternoon last year—a wet thunderstorm having passed through that morning as other storms would come and go during our stay. The moisture had left a sheen on the golden hills of the Palouse, a shimmer on the Blue Mountains to the east, accentuating the lushness of a valley full of opportunity and promise of the Chamber of Commerce variety. Driving in, it seemed still possible to start a successful business here, grow crops to take to market, to buy a house for a reasonable price, and settle into the friendly community.

I’d convinced Cheryl to travel to Walla Walla with me not for any of these long-term pursuits, but instead for a weekend of poking around in the lives of a particular missionary couple, the first white family to settle in the Columbia Basin. Marcus and Narcissa Whitman had also found the area lush, inviting, when they arrived in 1836. They planned to stay until they were old and frail, doing the work they felt they’d been called to do, but instead they’d met a violent end in 1847. They’ve been cast as martyrs of the West, as “angels of mercy,” ever since.

It’s Narcissa Whitman who’s long fascinated me. She’s been billed as the first white woman to cross the Rocky Mountains, having stepped over the Continental Divide (with co-missionary Eliza Spalding on her heels) on July 4, 1836. I feel a certain tie to her as one of the millions of white women born in her wake. I’m a fifth-generation Idahoan, and lately curious about a legacy that I believe reaches all the way back to her.

Narcissa and Eliza, on their long journey with husbands Marcus Whitman and Henry Spalding, as well as an entourage of more seasoned trackers and mountain men, traveled alongside a single wagon of belongings (they’d started out with two wagons; the larger one was abandoned at Fort Laramie). Though the small Dearborn actually belonged to the Spaldings, it carried, among other items, Narcissa’s precious trunk; in that trunk were bright print dresses Narcissa thought “would delight the savages across the mountains,” and boxes of her dishes and books. This wagon, splintered, beaten up, in need of constant repair to the point that it was finally reduced to a two-wheel cart, was fairly dragged over the daunting range of jagged peaks. Still, news of the accomplishment reached those east of the Mississippi enthralled with the “frontier,” a mysterious land of plenty where they believed they could start their lives over again. Because Narcissa Whitman—far from a sturdy outdoorswoman—had made the five-month trip, sleeping on the ground, cooking with buffalo chips, eating dried meat for weeks on end, as men coaxed a wagon over rough terrain, many others, including my own ancestors, were certain they could do the same.

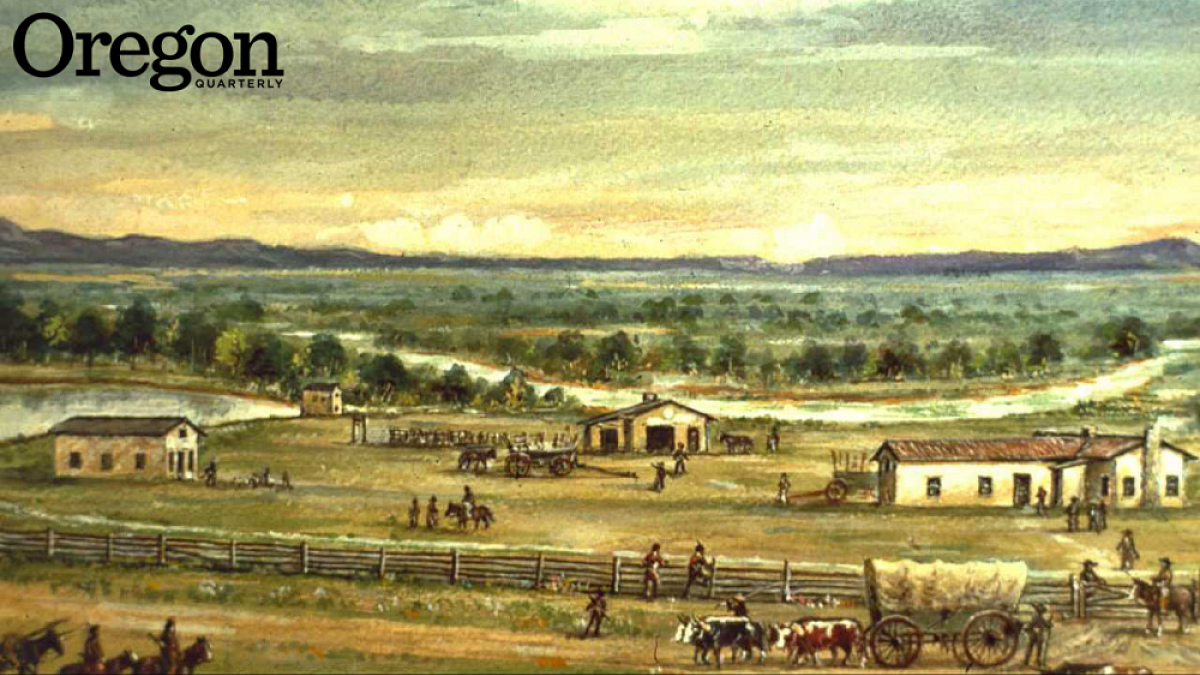

I’d insisted we stay at the overpriced hotel, opulent (in an old-fashioned sort of way, from brocade on the sofas to dusty chandeliers) beyond any standards Marcus himself would have tolerated. He was perfectly happy in the simple lap-sided house he’d built for his wife and the child conceived on their journey west. (Their home and outbuildings, gone now, were located eight miles from the hotel at the Protestant mission called Waiilatpu.) Guests of the hotel, built in the late 1920s by local citizens in Marcus’ honor, can stroll through an art gallery, perusing the thirty-five oil paintings depicting an ever-serene couple, Marcus and Narcissa, from their perfunctory wedding in Amity, New York, to the day in November 1847 when their skulls were split open by the Cayuse Indians who they’d come to “save.”

Soon after we’d dropped our bags in the lavish suite, we returned to the front desk. I asked the young clerk to guide us to the gallery, and she pointed to a staircase, handing me a brochure about the artist, Dave Manuel, who began his work in 1972, based largely on Narcissa’s journals and letters home. He’d finished the paintings, pure hagiography, in time for the nation’s bicentennial. I’d read many books about Narcissa and Marcus, and during a month at the American Antiquarian Society Library in Worcester, Massachusetts, I’d done little but try to wrap my head around their missionary drive, tightly locked with the spirit of Manifest Destiny that had gripped the nation in the mid-1800s—so I was disingenuous when I asked the clerk who Marcus was.

She shrugged, turned a little red in the face. “I’m not sure. There’s a statue of him down the street,” she said, pointing in a different direction. “I think he’s the first one to settle in this area. A missionary, maybe?”

Sure, this is the fate of most founders—who recalls much about the character of, say, Lt. Peter Puget, Judge Matthew Deady, or even Eugene Skinner?—but I was disappointed that Marcus and, I assume, his wife were so sketchily recalled. I was about to argue the importance of studying their lives, their time here in the Columbia Basin, these people who were the forebears of local agricultural ambitions and religious principles, but the clerk looked bored with me. I glanced around at groups of women and men in colorful weekend garb studying maps and making plans for hours of imbibing. I realized that I, too, was ready to indulge in the delights of the small city. We skipped Dave Manuel’s earnest images for the time being, and headed to the bar, where Cheryl and I shared a plate of morel ragu, topped with grilled asparagus and a duck egg. The meal was delicious enough that we returned the next evening and ordered the same. And, despite my research subjects’ disdain for such an activity, we shared a bottle of Marcus Whitman red wine, produced especially for this restaurant, available nowhere else, and so smooth, so polished, I leaned back in the fat chair and sighed with pleasure.

* * *

Narcissa Prentiss Whitman, raised in upstate New York by a mother who was quietly yet doggedly fervent in her religious beliefs, was one of thousands swept into what’s known as the Second Great Awakening. Narcissa’s spiritual rebirth came early, at age eleven, and it set her in the one and only direction for her life that she would accept: she was to become a missionary. “I frequently desired to go to the heathen but only half-heartedly and it was not till [her religious transformation] that I felt to consecrate myself without reserve to the Missionary work waiting the leadings of Providence concerning me.” She was certain she held the answers to life’s predicaments and could guide others on the only righteous path to Eternity. Crowds of others who felt the same jammed churches in the Finger Lakes District. They swooned over the Arminian theological tenets of personal salvation, a one-on-one relationship with Jesus, and the belief that “every person can be saved through revivals.” Such practices would remedy the evils of society, straighten the moral fiber of the populace, and allow the return of the Messiah. Here’s how Nard Jones in his 1959 book, The Great Command, describes the movement: “The romanticism of the first half of the nineteenth century has been called ‘the most widespread intellectual force ever liberated in the United States.’ Mixed with Puritanism and Calvinism, with Jeffersonian democracy and the frontier spirit, it became, moreover, a highly explosive force.” This fervor spread through East Coast churches, their brethren directed to bring enlightenment to those considered heathens, to convert native tribes all over the globe to Christianity, and to introduce them to a democratic system of government. Narcissa had read, as did thousands of others, an 1833 story in the Christian Advocatenewspaper that fit perfectly with this calling. The story was about four “Flat-Head” men (actually, Nez Perce) traveling a tremendous distance to find William Clark (whom they remembered from his 1805 passage through their country) in Saint Louis. The Advocate report insisted that they’d done so out of a desperate desire to know the Bible. But an interview with a Nez Perce elder in 1892, written up by ethnologist Alice C. Fletcher, casts their intention in a different light: “Old Speaking Eagle was of a philosophic turn of mind, and the question as to whether the sun was father and the earth mother of the human race was one that occupied him. . .” When Speaking Eagle heard about the white man’s Jesus, son of God, he wondered, “How can the sun make a boy?” Fletcher continues: “It was the discussion of such questions as these that led the four men to determine to find the trail of Lewis and Clark and ask them about facts concerning the sun and the earth.”

Narcissa’s interest in applying to the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions was ignited after reading the Advocate story. But she knew that a single woman would not be allowed to travel to the frontier West (the ABCFM had shipped single women off to India and the Sandwich Islands; the West, however, was a different matter), and that only marriage would get her there.

Narcissa was in her late twenties, considered an old maid in her community. It’s not that she hadn’t been offered marriage proposals—men had expressed interest, certainly, though some were put off by her tendency to attend church three, four, sometimes five times a day, her never-ceasing prayers, her even more religious mother looming over her. The suitors included Henry Spalding, a man she found (whom most everyone found) rude, backward, a whiner with too many sniveling complaints. She turned down Spalding’s proposal on the spot, not realizing that she would be stuck with him hounding her about her shortcomings all the way west, and every time he visited or wrote a scolding letter from his mission in current day Lapwai, Idaho, to her mission. As Jones writes, “He would never forgive her until she was dead.”

Just when a husband—and thus missionary work—seemed beyond Narcissa, she heard about Marcus Whitman, a doctor in his thirties whose calling was every bit as burning as hers. He heard about her, too, and traveled to Amity for a visit. After a couple of hours of discussion with him in her parents’ parlor, she emerged engaged.

Marcus and Narcissa met only once or twice before their wedding. They exchanged letters during the periods they were apart (including the eleven months of Marcus’s “trial trip” to the western frontier in 1835, when he surveyed the terrain, met native people and errant mountain men, and experienced plenty of travails). They knew nothing of each other’s habits or predilections, but no matter. Since the board of missionaries insisted that only legally wedded couples could go west, a marriage certificate would get them to the land called Oregon. The two near-strangers stood in her family’s Presbyterian Church on February 18, 1836, Narcissa swathed in a black bombazine dress, and were hastily pronounced man and wife. Then they were on their way, with stops to raise funds and garner support and find equipment for the long journey to the very ends of the Earth as they knew it. Narcissa Whitman, described as “buxom,” “curvy,” “substantial,” five-foot-eight and one hundred thirty-six pounds on her wedding day, headed west with the gangly and sometimes overwrought Marcus, never to return, never again to see the parents and sisters she adored. She was twenty-seven years old and a few months after the launch of their journey, she was pregnant for the only time she’d bear a child.

Narcissa gave up every comfort in life so she could spread her message to a tribe, it turned out, who hadn’t asked for it. They didn’t want it, they had not traveled to see General Clark and ask about the white man’s Bible, they did not tie boards to infant skulls to flatten foreheads. Yet they were nearly destroyed in the end because the Whitmans had moved to their country and practiced among them.

The Whitmans’ profound lack of awareness toward the Cayuse catalyzed a simmering anger that exploded on a cold November day in 1847. Thirteen people, including Marcus and Narcissa, died horribly, and their deaths set in motion vast changes that helped shape the West. News of the violence at Waiilatpu reached those forming a government in Oregon City, inciting former mountain men and frightened settlers to enact laws that made it easier to remove native people from their lands, not only to support commerce but also to create administrative and enforcement agencies suited to Anglo needs. Lawmakers in Washington, D.C., swiftly voted to create a territory called Oregon and to place it under U.S. rule, never addressing the sovereignty of the nations already established there. And war—which would nearly decimate a tribe already half wiped out by illness—was declared on the Cayuse and any tribe that might aid the Cayuse.

In a strange way, I see now, the Whitmans were as appropriated for others’ needs and notions in their own day as they are today. Back then, they were instantly turned into iconic martyrs, the violence of their deaths used to inflame fears and to promote political causes. These days, Narcissa and Marcus are reduced to a name on a hotel, a label on a bottle of wine, a statue of him downtown, of her at Whitman College. Hardly remembered for the forces they were when they lived, for the ideals and principles they brought west, many of which continue to resonate through the nation’s mythology, reinforcing our image of the American frontier.

* * *

On Saturday, Cheryl and I drove out to Waiilatpu. In contrast to the hundreds of cars in winery parking lots and tourists filling the streets downtown, we were the only visitors at the mission site. We were alone wandering through the displays, peering into glass cases full of native tools, implements, baskets, and, across the room, a pair of Marcus’s glasses, a torn Bible, a few chipped dishes rescued from the mission after the Cayuse burned it. In the center of the room on an elevated platform, a tableau mimics the first encounter of missionaries and Cayuse—a clumsy effort, considering that these life-size mannequins were designed to display spring outfits or fetching bikinis in a department store window, not the ill-fitting and faded pioneer dress on Mannequin Narcissa or the buckskin coat and coonskin hat on Mannequin Marcus. The Cayuse female forms are small—teenaged-size—with faintly darker skin. They carry baskets and wear hats expertly woven from the native grasses that once dominated the landscape. The Indian women gaze with wonder at the newcomers who’ll change their lives forever.

We noticed that the rain had lifted—threat of lightning gone now—so Cheryl and I went out to the mission grounds. I wanted to stand at the exact spot of Narcissa’s death as it’s been chronicled by survivors’ reports; I wanted to wander by the grave (all thirteen buried together), and then locate her baby’s headstone, lost in the brushy hillside. We strolled across green grass mowed meticulously, as if for a golf course, stopping to read a sign explaining that the National Park Service had begun to restore the meadows and hillsides to the original rye grasses and riverside tule, the prime vegetation there when the Whitmans arrived. Though the missionaries continued to call the location Waiilatpu—“place of the rye grass people”—one of Marcus’s main goals was to yank up the grass, to plow it under and teach the native people to become farmers who’d stay in one spot, grow food, live in homes, resign their nomadic ways. Evidence of his efforts abound at the site: the thriving peach and apple orchard near the river where their daughter Alice drowned at age two, his ingenious series of irrigation canals, the (reconstructed) grist mill silent now in the stream.

The killings at Waiilatpu, and the resulting war, closed the valley to settlers until around 1860. But after that, families moved in and farming took hold—dryland farming, with just enough rain off the Blue Mountains and some of the planet’s best topsoil making this a nearly perfect place to grow wheat and legumes. Cheryl and I had visited another museum, at Fort Walla Walla, earlier—a series of giant warehouses displaying massive enactments of former agricultural practices, the “33-mule team with Harris Combine & Chandoney Hitch,” in particular, with all thirty-three animals straining at the bit. This museum is replete with mannequins, as well—that team of horses (plaster mules apparently not available), with human forms at the helm of the combine and hanging from the sides, all of them dusty and so dented and marred that just standing there, I felt distinctly that the heyday of harvesting wheat off steep hills has passed.

The vintage I kept my eye out for was, of course, Narcissa Red. The name, which I’d only recently heard, had both fascinated and repelled me since I’d read this description on a local website:

“Ask about the story of Narcissa Whitman, the namesake of Whitman Cellars’ red blend, and you know you’re in for a serious wine. The ‘W’ on the bottle stands for Whitman, the brave and idealistic young couple Marcus and Narcissa who traveled west to set up a Christian mission amongst the Cayuse people only to be killed before their time. Narcissa was one of the first women to cross the Rocky Mountains and make it to Walla Walla. Along with their religious ideals, the Whitman’s [sic] unfortunately brought disease with them, and their pathology wiped out the children of the Cayuse. So it was a matter of survival for the locals that the Whitman’s [sic] be killed and the buildings of their mission destroyed. This is just the kind of story that inspires strength and perseverance, and the story has resonated in the area ever since.”

It’s not clear which part of the story “inspires strength and perseverance” or even which part still resonates—though I find it curious that the author of this paragraph fails to note Narcissa’s disdain for alcohol of all types. Nor has he researched enough history to understand that it was not the Whitmans who brought illness to the valley, but the measles- and typhoid-ridden wagon trains that moved down the Oregon Trail and often stopped at Waiilatpu for supplies and rest beginning around 1843. It’s true that at least half of the tribe died from pathogens against which they had no defense. The crux of trouble for the Whitmans, however, was that the Cayuse couldn’t fathom why Marcus, who had presented himself as a medicine man, was unable to effectively mitigate the epidemics. In Cayuse tradition, a tewat who could not heal had to pay with his own life.

* * *

Narcissa’s adopted daughter Catherine Sager, in her eyewitness description of the mayhem, reported the events this way:

“Mrs. Whitman was shot through the face as she lay on the settee. Every groan the sufferer made was answered with blows from clubs. One Indian had her by the hair when another shot at and missed her, the ball going through the hand of him that was pulling her hair. When they thought life was extinct, they threw her into the mud, and night coming on, they left. . .” Catherine describes the children, including herself, huddled alone upstairs, drenched in Narcissa’s blood and crying out for water. “Never shall I forget that awful night. I think of it now with a shudder. I wished that it might always stay dark, or that we might be crushed by the roof falling on us.”

* * *

So, yes, even one hundred sixty years after her death, a “serious” red wine seems rather insensitive.

When I spotted the Whitman Cellars winemaker slipping out to his car and away from the lively crowds, I followed him. He let me ask him a few questions in the parking lot about his decision to name this wine after Narcissa Whitman. He regarded the label as a way to honor her, he said. And, yes, of course, he knew how she’d died. He folded his arms across his chest, not unfriendly but impatient. I could tell he’d faced these questions before, and I really had no new way of reiterating the obvious: a strict teetotaler, a deeply religious woman, whose hastily buried body was dug up by animals, reburied by the surviving women and children, then dug up again, the hanks of her red hair left strewn across the wet meadow—just how could you consider it an honor to put her name on a bottle of red wine?

Although I don’t recall his exact words, the winemaker finished our conversation with a sentiment that stuck with me, so much so that I turned it over all that night, so that I turn it over still. Basically, he said that Narcissa Whitman’s time in the Walla Walla Valley had led to thisreality—the development of rich agricultural lands, to thriving farms, and, more recently, to an acknowledgement that the loess soil, deposited by ancient glaciers, makes for terrific terroirand, thus, terrific wine. This reality, no other. The Whitmans came to set change in motion and set change in motion they did, though not the ones they’d planned for. I believe the winemaker was asking me, What good does it do to pretend otherwise?

* * *

After he left, I went back inside and purchased some Narcissa Red wine. An odd choice, I suppose, given the objections I’d just expressed to the winemaker about the label. Uncomfortable as it is to admit, his logic made sense to me. I’m as much a product of my time as the clerk at the hotel and the others who’ve let the Whitmans drift into folklore; those ready to promote only the present, the further development of former Cayuse lands and the unexamined commercialization of Western history, which seems to be working out well for nearly all of them—except, it seems, for Whitman Cellars, which closed earlier this year, after defaulting on several loans.

Cheryl and I actually bought a case of Narcissa Red and brought it home. I opened my six bottles slowly, over a long period of time and only for the most special of occasions. Every time a cork pops, I think of Narcissa: way back there at the start of a history that leads to today, to me and others like me rooting through the folklore and mythology of the West, trying to make peace with the contradictions of the past.

I did visit the art gallery at the hotel before we left on Sunday morning. I stayed only a few minutes, as put off by the images, the overselling of her as a saint unflinching in her devotion, as I am by Narcissa’s name on the bottle of wine.

The night before they died, according to Nard Jones’s biography, Marcus returned home from the Indian encampment aware of the brewing anger aimed at him and his wife. The two sat up past midnight, whispering so as to not alarm the nine children in their care—many in their beds near death from the measles. Narcissa wept as her husband warned her of the violence they would surely face, but she didn’t beg him to pack up and leave. Nor did he offer to get her away from there, from danger. The Whitmans, whether or not they admitted aloud to one another the mistakes they’d made, the shortfalls of their efforts, held on to each other and chose to endure the consequences of their eleven-year sojourn at Waiilatpu.

Most histories, including the one depicted in the Manual paintings, jump over this moment of reckoning, this acknowledgement between the couple that things would not end well. That’s too bad. The fear and the doubt that plagued them that night make Marcus and Narcissa more real and more brave. I prefer to remember her this way: afraid, yet stalwart. Full of despair, yet unyielding in her determination to care for those who depended on her. Maybe even, perhaps, ready to accept that she had helped bring this on.

There’s much still to sort out. But alone in my home in Oregon, a century and half past the end of Waiilatpu, I pour the wine named for her in a glass. I swirl it until the red color deepens. Before I drink, I lift the glass and toast Narcissa Prentiss Whitman. All that she came with, all that she left behind.

—By Debra Gwartney

Debra Gwartney is working on a book about Narcissa Prentiss Whitman. She first wrote about her for Old Oregon (“Narcissa,” Winter 1992). Gwartney, winner of the 2000 Oregon Quarterly essay contest and judge for that contest in 2011, is the author of Live Through This: A Mother’s Memoir of Runaway Daughters and Reclaimed Love (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009) and is on the faculty of Pacific University’s Master of Fine Arts in Writing program. She lives in Finn Rock.