In early 1960, the Erb Memorial Union hosted the annual Parents Weekend combo contest for student musicians. Freshman Glen Moore '63 showed up with his acoustic bass, anchoring the rhythm section of three of the five jazz groups slated to perform. Moore listened closely to the other students. One especially stood out. "He was playing a little piano, then trumpet, and even bongos. He even had a bongo solo!"

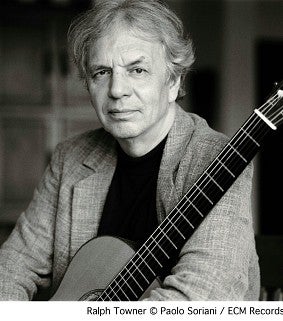

The sophomore pianist noticed Moore, too. "He had a sound right from the beginning," Ralph Towner '63 remembers. "He had those big strong hands." Although Moore was playing an acoustic instrument, "he'd hit a note on the bass and there was electricity right away."

That highly charged first meeting of bassist Glen Moore and the bongo-playing pianist, Ralph Towner, sparked the most durable and acclaimed musical combination ever to emerge from their home state—”whose name they eventually took a decade later, a continent away, when they formed the jazz and world music quartet Oregon.

The two young jazz musicians began jamming and then performing together. Soon, they would join forces with a third nascent star of the university's fertile turn-of-the-decade jazz scene ”another student whose sublime voice and instinctive understanding of song interpretation also impressed listeners at one of those Friday Fishbowl gigs. When the sponsors asked Nancy Whalley, as she was then known, to help organize and lead another of these events later in the term, she made a point of listening to other student performers so she could recruit top talent for her backup band. When she heard Towner and Moore, she immediately noticed their musical skill, and also, like Towner, Moore's "great big hands. I love hands. The girls all thought he was beautiful ”he had that same kind of animal crazy that Jim Morrison did."

She approached them. "Hi, I'm Nancy. I sing and play drums. Would you be willing to get together with me?"

"What are you doing right now?" Towner replied. They repaired to a university piano practice room. "Ralph sits down at the piano," she recalls. "He touched the keys and I lost my mind. He sounded like [preeminent jazz pianist] Bill Evans, and I idolized Bill Evans."When they performed together for the following Friday's show, "People went crazy!" she remembers. "They kept coming up to us and saying, 'You guys are really good!'"

They were—and are. By the end of the century, Nancy King (she changed her name after she paired with San Francisco saxophonist Sonny King later in the 1960s) had built a reputation among the cognoscenti as perhaps the finest jazz singer alive. At this February's Portland Jazz Festival, she was crowned a Portland Jazz Master and performed in duo showcases with her longtime piano accompanist Steve Christofferson and with her big-handed bass partner, Glen Moore. Oregon, too, is still going strong. In the coming year, the quartet is scheduled to headline the Portland Jazz Festival—54 years after its two principals met in the EMU.

The three musically precocious students entered the UO at the peak of jazz's popular and critical approbation. Several of the albums released that year—Miles Davis's Kind of Blue, Ornette Coleman's The Shape of Jazz to Come, Charles Mingus's Mingus Ah Um and Blues and Roots, Dave Brubeck's Time Out, John Coltrane's Giant Steps, Bill Evans's Portrait in Jazz, Thelonious Monk's At Town Hall, Ella Fitzgerald's Gershwin Songbook—became classics not just of jazz, but of American and 20th century music. In 1959, it seemed possible for a college student to imagine a life in music that was simultaneously art and pop.

But though they didn't know it at the time, jazz was about to be shoved aside (at least in mainstream consciousness) by rock and other popular genres. Towner, Moore, and King would experience this shift firsthand, embarking on their careers just as jazz moved from the center to the margins of popular culture.

* * *

Four years later, she received a scholarship to study music at the university, even though her flitting mind—"I was ADD before they knew what ADD was"—and inherent musicality conspired against her learning to read music. A sympathetic professor heard her sing and wangled a scholarship contingent on her commitment to learn to read music and to join the University Singers.

While at the UO, King worked at the McDonald movie theater in Eugene, where she could listen to the great film singers. She played regularly with Towner, who lived above a restaurant where they got a job playing standards for diners and dancers several times a week, packing the house many weekends with students. "Nancy was crazy but brilliant," Towner recalls. "That was a chance to develop under fire, like getting thrown in the swimming pool to learn how to swim. We got some really good experience."

* * *

Ralph Towner had played in adult dance bands even as a teenager growing up in Bend, where his mother was a church organist and piano teacher and his dad a trumpeter. Like King, Towner (born in Chehalis, Washington, in 1940) and his four siblings enjoyed a music-filled childhood. "I wouldn't sit still for my mother's piano lessons because I could imitate the records by ear," he recalls.

Towner majored in composition, studying with "a wonderful professor named Homer Keller," and getting by on talent more than discipline. "I had a way of hearing a certain kind of music and understanding its language, how it manages to convey feeling or emotion," he remembers. "I was very good at writing Bach chorales without studying in the theory class. I just knew how it worked. But I was always waiting till the last second. At the end of the year my freshman theory teacher said to the class, 'Unfortunately, I have to grade for quantity and not quality, so I have to give Ralph a B' instead of the A I deserved. But it backfired. I wasn't challenging myself. I didn't know any better."

* * *

Glen Moore was already a veteran musician by the time he arrived in Eugene in 1959, a year after King and Towner started at the UO. As a teenager growing up south of Portland, he'd performed as a member of the Young Oregonians, a traveling troupe of 50 young talents, sponsored by the Portland newspapers, who barnstormed the state by bus. He also played background music on solo piano for banquets and other events. After the streetcar stopped running from his parents' home in Milwaukie and he could no longer easily get into downtown Portland for lessons, Moore realized he needed exposure to a bigger world of music. The UO beckoned.

Once while playing at a dance, Moore was startled upon suddenly encountering an unexpected key change on the bridge of a pop tune. He froze, finding his way back into the tune a few measures later. Afterwards, the grizzled band-

leader whirled and growled, "Why didn't you play that note?" "I didn't know it," Moore stammered. "Then play anything, even if it's wrong, but never leave a note out and make the dancers stop." "That was a pretty rich and wonderful—sometimes terrifying—setting to try new stuff," Moore remembers.

Moore studied literature and history, and fondly recalls history courses taught by Stan Pierson '50. But he quickly found out where the pianos were at the music school, and signed up for lessons with a grad student who'd been a serious pianist back east. Moore was deeply influenced by some of the great jazz pianists of the time—Dave Brubeck, Ahmad Jamal, Oscar Peterson, Billy Taylor, Erroll Garner—and studying their music helped him understand chord structures. The school lacked a faculty bassist, so he studied with cello professor Robert Hladky ("he hated the bass") but realized that the cello was too small to work in an acoustic jazz combo.

Another UO mentor, Chuck Ruff, had been a jazz pianist in New York before being injured in World War II, and Towner's roommate, Jack Murphy, was a serious jazz bassist who threw occasional gigs Moore's way when Murphy was already obligated (as he happened to be on the day of that providential combo contest when the three stars-to-be first aligned). They introduced both Towner and Moore to the jazz of the day. Moore also took private lessons and played gigs (including modern bop) during the summers when he went back to Portland.

But amid all the various and ever-changing configurations of musicians in and around the university at that time, there was, Moore recalls, something special when he, Towner, and King played together. "Nancy was like a dream," he says. "It was like playing with a Marilyn Monroe who was an Ella Fitzgerald sound-alike. It made my knees weak to be in the same room with this beautiful woman." (Apparently he wasn't the only one. King remembers once causing a driver, distracted by her shapely legs, polka dot chiffon dress, and teenage beauty, to drive up a curb and through the window of Eugene's Cadillac dealership.)

* * *

But the trio's partnership proved short-lived. This was a tumultuous and at times terrible period for King, marked by events that moved her away from Eugene and further into her musical career. The nascent civil rights movement was starting to affect the UO campus, and King had dated some black football players, who, she recalls, at that time were restricted to their rooms after dinner. King says that football coach Len Casanova warned her to leave his players alone, but she refused. She tells the story of participating in a protest against the discriminatory conditions, chaining herself with other students to the library doors; a half dozen of her fellow protesters spent the night in the Lane County jail.

It wasn't only her politics or a run-in with the law that convinced her it was time to move beyond college. She recalls a party at a friend's apartment that turned into a nightmare when a trio of party-crashers got her drunk (the first time she'd consumed alcohol), raped her, and left her passed out, bruised, and bleeding. Not long after this, a liaison resulted in her becoming pregnant; her parents sent her to a home for unwed mothers for the duration of her pregnancy (she temporarily lost custody of the baby, then regained it).

After that, she visited a former roommate, now married to a jazz saxophonist in San Francisco who needed a singer, and from there, she was quickly and fully immersed in the Bay Area's rich jazz scene.

King returned to Oregon in the late 1970s as a single mother, raising her growing family (she'd had two more children with jazzman Sonny King) and gradually building a reputation performing around the country. She's now recognized as perhaps the greatest jazz singer of her generation. "Nancy King is a marvel of perfect pitch, phrasing, dynamics, inventiveness, and honest emotion," says veteran jazz journalist Doug Ramsey.

* * *

Moore, too, got involved in the racial conflicts of the time, marching in campus protests in 1963 and '64. A roommate had gotten him into a fraternity that needed a bass player for its parties. He paid his way, in part, by working in the kitchen. But one night at a house meeting came the announcement of a rent increase. Unable to afford it, Moore knew he'd soon be moving out. But before he took action, an official from the Greek house's national office visited and addressed the group. "You've been hearing that some of the national fraternities are beginning to pledge coloreds," the man said. "I'm here to tell you that we're not gonna do this." Making a virtue of necessity, Moore rose and announced, "Then I quit."

With King gone, Towner and Moore—both Bill Evans aficionados—honed their chops playing gigs wherever they could find them: in dorms, at fraternity and sorority events, venturing to the coast to liven up a logger bar, and once getting $100 to play at a high school homecoming party in Drain.

"I was like a big empty bowl," he says, ready to be filled with new musical ingredients. By then both his parents had died, and he had no obligations. "I needed to do something that drastic," Towner remembers. "I was undisciplined, winging away on pure talent. I came back with a new life." He borrowed $100 for the return flight to the United States and, broke, hitchhiked back to Eugene.

Towner got a job at the local cannery and enrolled in graduate school, but never got his master's degree. He detested the then-trendy thorny music of academic modernist composers like Milton Babbitt. He played a couple of classical guitar gigs where "there was nothing but bile coming out of the audience," and "the guitarists who played better than you hated you, and the others thought they should have had the gigs. And they all played the same few pieces," he says. With classical composition and classical guitar performance off the table, "I realized what I wanted to do was what I'm doing now"—playing original, partly improvised music that touches hearts and souls as well as minds. He moved to Seattle for a year, then to New York.

After taking a few UO graduate courses, Moore, too, thought about going for a master's degree in history. One of his teachers came to hear him perform. "Why would you want to teach history," he told Moore, "when you can make history?"

In 1966, Moore headed north to Seattle, where he met jazz legends-to-be like Larry Coryell and Michael Brecker. He and his wife followed Towner's footsteps to New York, then to Europe, living briefly in Copenhagen. Then they headed back to Seattle, then Vienna, then met up with Towner in Portland for a few months. Eventually, the musicians wound up back in New York, where they joined folksinger Tim Hardin's band in time to play the original Woodstock Festival in 1969. They joined the pioneering Paul Winter Consort the following year, and then, with another Winter alumnus, oboist Paul McCandless, formed the ensemble Oregon. This group has since released more than 25 albums; created a unique blend of jazz, classical, and world music, and its members have also maintained productive solo careers on the side. Along the way, they've played with many of the major figures in jazz and beyond.

Moore returned to Portland in 1980, often reuniting with King for duet performances that still melt the hearts of anyone lucky enough to hear them. "Since we'd met 18 years before, I'd been to New York City, toured around the world, all sorts of things," he explains. "But we were like already old souls meeting. And I could finally play up to her standard."

In the years since the three fledgling musicians left Eugene, jazz has declined in popularity. Yet Towner, Moore, and King have persevered, managing to forge their own original approaches and make a living doing so—without compromising their individuality or artistic integrity. The university helped pave the way. At the UO, Moore and Towner first deeply immersed themselves in classic jazz and first encountered the classical guitar sounds that still inform their work separately and together. It's where the once naive King learned how to sing jazz and hold the stage, and also where she confronted and surmounted daunting challenges that toughened her enough to survive even more severe difficulties—health problems, family crises, financial troubles—along her rocky path to jazz immortality.

Most of all, it's where they found each other brilliant young musicians whose natural skills were augmented by a determination to follow their own personal creative paths, regardless of cultural trends or personal setbacks.

Though she usually sticks to venerable standards, no one sings jazz like Nancy King, who, like Moore, lives in Portland and is a member of the Oregon Jazz Hall of Fame. Towner has lived in Rome for many years, but visits the Northwest regularly; the band always draws an enthusiastic crowd when it plays at the Aladdin Theater on its occasional reunion tours.

If you listen closely to Oregon's music, even in works composed half a world and half a century away, pastoral tunes like "Green and Golden"and "Distant Hills," you might hear echoes of their Northwest origins. And there's no missing the chemistry that Moore and Towner, and Moore and King, still display when they perform together. More than 50 years on, the magical musical partnerships first forged in the Fishbowl continue to flourish.

—By Brett Campbell

Brett Campbell, MS '96, lives in Portland and writes about classical music for Oregon ArtsWatch, Willamette Week, San Francisco Classical Voice and other publications.