The Spanish flu of 1918 was the first pandemic to occur in the era of “mass society,” when public access to transportation, education, and amusement vastly increased the ability of communicable diseases to spread. When the flu hit the University of Oregon, members of the campus community drew together to care for those who were ill, with the president’s wife personally watching over many students. In 1918, University of Oregon president Prince Lucien Campbell faced a challenge no UO president had faced before: guiding the university through a mysterious, deadly plague. Day by day that fall, he watched students and faculty sicken and die from the Spanish flu, a pandemic that killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide. But by proactively using the tools of organization, communication, and caring, Campbell prevented potential devastation of the campus community.

The 1918 Spanish flu epidemic is “America’s forgotten pandemic,” writes New York Times science reporter Gina Kolata in her book Flu: The Story of the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918. “Nothing else—no infection, no war, no famine—has ever killed so many in as short a period.” The United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917. Eleven months later the deadly influenza first appeared in this country at Fort Riley, Kansas. Thousands of soldiers there got sick, and 38 died. Then, “as summer arrived, the flu seemed to vanish without a trace. But a few months later [it] was back with a vengeance.” It reappeared among troops in Boston on August 28, and within days was roaring across the country.

No one knows where the epidemic started, but it hit Spain particularly hard, sickening King Alfonso XIII, so the world press nicknamed it the “Spanish flu.” Normally, influenzas kill one percent of the people they sicken, but this influenza killed 2.5 percent. Most of the people who died were healthy young men. “Every other influenza, before and since, has killed the very old and the very young, sparing healthy adults in the prime of life, but nearly half of the influenza deaths in the 1919 pandemic were young adults 20–40 years of age,” writes Kolata. The respiratory illness was spread by coughs, sneezes, and personal contact, and it decimated World War I military personnel, who were crowded together on troop ships and in barracks. And so the UO’s 1,375 students, many living in student housing, were at high risk. To compound the threat, the UO did not have an infirmary.

On August 4, Eugene’s leading newspaper, the Morning Register, reported that at Camp Lewis, in Tacoma, Washington, “Health in camp is good. No deaths in week among 29,887 men. The epidemic has been thoroughly overcome.”

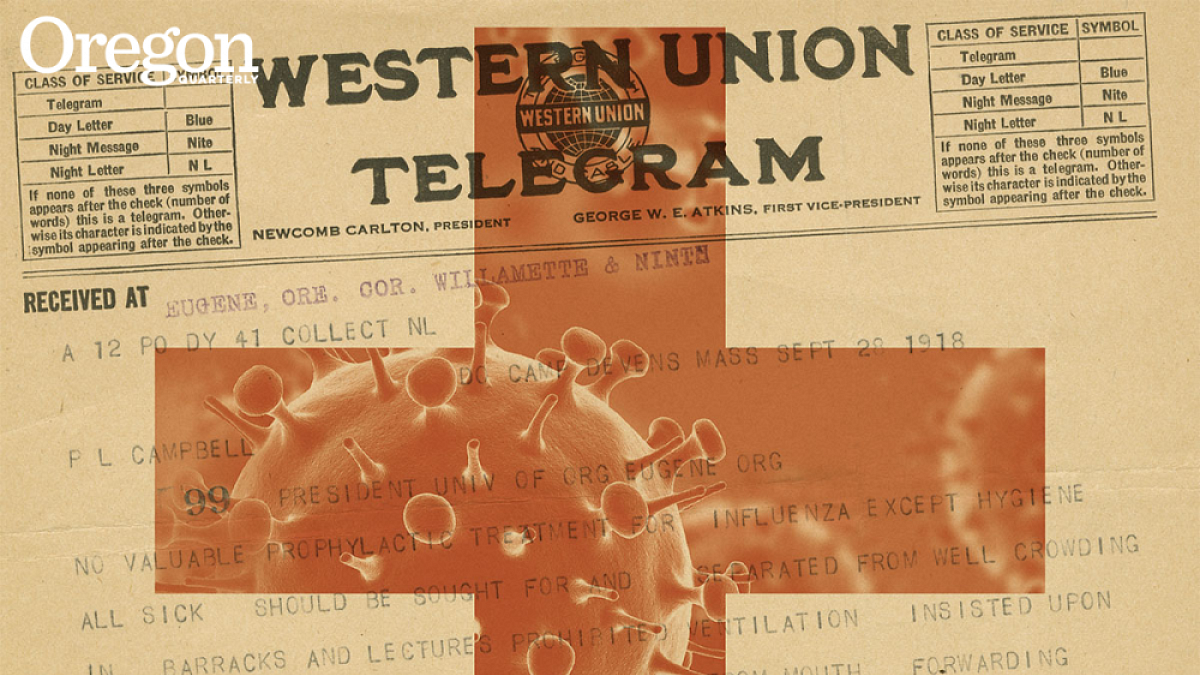

But within a month, the second wave of the deadly influenza hit the country. Soldiers stationed near Boston began getting sick on September 8, and by September 28, 100 soldiers a day were dying at Fort Devens. Campbell contacted Fort Devens for advice, and received a Western Union telegram from Lieutenant Colonel Condon C. McCormack, a surgeon stationed there: “No valuable prophylactic treatment for influenza except hygiene//all sick should be sought for and separated from well//crowding in barracks and lectures prohibited//disease spread by spray from mouth//forwarding detailed suggestions by mail.”

Campbell acted proactively. For years he had been lobbying, unsuccessfully, for money to build a student infirmary; now he began to organize temporary hospitals on campus. On October 5, the Oregon Daily Emerald announced that “beginning Monday, every student and every member of the faculty must report daily at sick call in case he is suffering from any illness, however slight it may appear. It was decided that every suspected case would be isolated for observation and treatment. Infirmaries for men and women respectively are now being put in shape and will be ready in a few days. The women’s infirmary is in a nine-room house on University Street, just back of the women’s gymnasium, while the men will use the residence on Twelfth Avenue east formerly occupied by the Phi Gamma Delta fraternity.” Students who stayed in the infirmaries were charged $2 a day.

Campbell’s wife, Susan Campbell, helped organize the campus infirmaries. She had joined the university in 1905 as supervisor of student living, then resigned and married President Campbell in 1908. She worked ceaselessly throughout the crisis, visiting ill students and providing their parents with updates.

The plague roared toward Oregon. “Influenza has spread to civilian population,” the Register reported on October 3. “Information coming to the public health service was that the disease was rapidly spreading among the civilian population of the country. The malady has appeared now in 43 states . . . it is epidemic in Virginia, South Carolina, and other places.” That day, Robert Claude Still ’14 died of influenza at Camp Colt, Pennsylvania. His brother, Lloyd, was attending the UO.

On October 4, the Register reported, “Epidemic reaches Denver.” And on October 8, two days after Campbell celebrated his 57th birthday, the paper announced, “Four cases of Influenza reported in Portland.”

The next day, the influenza struck Eugene, sickening several university students.

On October 1, Congress appropriated $1 million to the US Public Health Service to “combat and suppress” the Spanish influenza. The health service sent posters advising the influenza was “As Dangerous as Poison Gas Shells.” UO students began making posters, too, and by October 10, bright orange fliers with flaring black headlines went up around campus, with directions on how to prevent the spread of the malady. That day, the Register printed an article by A. R. Sweetser, head of the UO’s botany department, called “How to Avoid the Influenza.” Sweetser advised people to avoid all spitting, to smother sneezes in handkerchiefs, and to “abandon the one finger method of cleaning the nostrils.” Eugene closed all theaters and churches and banned all dances, but the university and the public schools were still open. At Camp Arthur in Texas, Earl S. Powell ’18 died of influenza.

The next day the first two people in Eugene died of influenza and the city closed the public schools. The UO remained open.

On October 10, former UO student Earl Cobb died at Camp Zachary Taylor in Kentucky, leaving behind his widow, Ada Kendall ’13, and their three-year-old son. By October 11, 237 UO students had influenza, as did economics professor Peter C. Crockatt.

Anxious parents jammed the university’s phone lines. Dr. John F. Bovard, dean of the School of Physical Education and chairman of the student health committee, later remembered, “I cannot but say a good word for the telephone operators, who stood so faithfully by when we were so seriously in need of doctors and nurses. There were times when I was at the telephone for two hours at a stretch, and instead of becoming tired or cross they stayed at their post and did everything they possibly could to help me out. They have my sincerest thanks.”

Some desperate parents turned to the US mail. On October 11, Robert Tate, in Portland, wrote to Karl Onthank, Campbell’s executive assistant: “Would you be able to give me some more definite information about the condition of my son, E. Mowbray Tate, staying at the home of Mrs. Hughes. He writes very briefly that he is sick, first with a bad cold and then that his stomach is in bad condition and that his fever is up to 102½. He does not say how he is attended, whether he has been removed to the hospital, who is his physician, so that we could write or call him direct . . .”

Onthank replied by letter the next day. “My dear Mr. Tate: I have just talked to Dr. C. W. Southworth, who is attending your son. He tells me that while the boy has a fairly severe case of the Grip he is in no danger. If it seems best for Mrs. Tate to come down here or the boy becomes seriously ill, you will be telegraphed at once. I believe that Mrs. Hughes, with whom he was staying, wrote to you last evening.”

By October 12, the UO had set up four emergency infirmaries: two for women, located at 1191 University Avenue and at the Kincaid House at 14th Avenue and Alder Street; and two for men, at the Phi Gamma Delta and Phi Delta Theta fraternities. They were staffed by volunteers. “Mrs. P. L. Campbell has been working almost unceasingly in equipping the infirmaries,” the Emerald reported.

The bright orange influenza posters blanketing campus were proving very popular. Army lieutenant Milton Stoddard ’17, stationed at Fort Stevens in Astoria, wrote to Onthank, asking for posters, saying he first saw and heard of the posters through an officer at Fort Stevens who received one from a University of Oregon student.

By now, the plague had spread across the globe, killing millions of people, and on October 15, it killed Turner Neil ’18 in Nièvre, France.

On October 16, influenza killed Charles A. Guerne ’12 at Camp Zachary Taylor in Kentucky. But in Eugene, Campbell was optimistic that the worst was over: in a letter to J. M. Day, of the United War Work Campaign, Campbell wrote, “The epidemic of the Influenza at the University has involved some two or three hundred of the students, but with the exception of three or four cases. there is nothing of a very serious nature. I think that probably we have passed the crest of the wave.”

Campbell was wrong. On October 17, Thomas R. Townsend ’09, who had returned to the UO to attend officer’s training school, became the first UO student to die of influenza. The next day, two more students died on campus: J. H. Sargent and Richard Shisler. On October 19, the UO lost sophomore Glen V. Walter.

On October 20, influenza killed former UO students Luke Allen Farley at Camp Pike, Arkansas; Kenneth Farley at Camp Lewis; and Richard Riddle Sleight ’14 in Portland. On October 21, freshman Emanuel Northup Jr. died at the Phi Gamma Delta infirmary, and former student William Allen Casey died at the officers’ training camp at Fortress Monroe in Virginia.

Panic and misinformation gripped the nation, and Campbell dealt with it in Oregon. From Roseburg, Mrs. M. M. Miller wrote to Campbell on October 17, “Will you kindly tell me if it is true, that the boys quarantined in the ‘Girls Gym’ are without any fire & if they are sick they are left there, still without heat and the sick and the well are huddled together?”

Campbell replied on October 28: “My dear Mrs. Miller: Please pardon the delay in replying to your letter of some days again. We have been overwhelmed with work in connection with the Influenza . . . At the Women’s Gymnasium, where some of the men were quartered, there is an out-door pavilion in which a number of the men preferred to sleep. They were allowed to exercise their choice in this matter, but there was ample provision made for them inside the Gymnasium where abundant heat was provided. It is absolutely not true that the men were neglected in any way. A very careful organization was made before the Influenza started, and this has been carefully maintained up to and including this present time. I am glad that you wrote me, and I certainly hope that you may correct any mistaken impressions in regarding to conditions at the University.”

On October 20, the Emerald reported, “There are 179 cases of influenza among all sorts of men and women of the University. Most of these are housed in the University’s temporary infirmaries and 40 are in the Mercy Hospital.”

David Foulkes, an executive at the Oregonian, sent Campbell a handwritten note on October 23: “Dear President: Nettie and I thank you sincerely for your interest in Celeste. Dr. Giesy says for her to go to her room when discharged from the infirmary and remain there until her strength is restored.”

On October 25, Campbell wrote back, “Your note of October 23rd is at hand. I expect to telephone you today in regard to Celeste. Mrs. Campbell is with Celeste this morning. We are both watching the case as carefully as possible. I am writing because I want you to know the situation fully. You can telephone to me at any time as to what you desire to have me do.”

Bovard announced on October 24 that faculty wives, led by Sally Allen, wife of School of Journalism dean Eric W. Allen, had made 10 dozen masks for university nurses and attendants. “Members of the SATC [Student Army Training Corps] here were ordered to wear gauze masks during the influenza epidemic if the situation seemed to warrant it, in a telegram received yesterday morning from SATC headquarters in San Francisco.” However, the US Army surgeon decided the situation did not warrant masks. “The epidemic is practically over as far as the Students’ Army Training Corps men are concerned,” said Colonel W. H. C. Bowen, SATC commanding officer at the UO.

That day the Emerald reported bits of good news: “Elmo Madden is spending the week at his home in Seattle while recovering from the influenza. Emma Wotton Hall, who has been ill with the influenza, is reported to be much better. Margaret Kubli has returned from Portland, where she spent the weekend recovering from the influenza. Ruth Nash has been discharged from the infirmary and is back at the Delta Gamma house.”

But on October 28, two more students died on campus: John Herbert Creech and Robert Gerald Stuart.

Campbell was reeling under the strain. On October 29, he wrote, “We have been overwhelmed with the work required by the Influenza . . . it has been extremely difficult to think of anything except the serious cases which are in the hospital . . . there are two or three about whom we are very anxious.” The next day, student Sanford Sichel died on campus.

Student David Stearns Jr. recuperated from the influenza in Portland with his family. On October 30, his father wrote to Campbell: “David has recuperated nicely and practically his old self again. He is anxious to return to his college work . . . unless conditions at the college are such that if he were your son you would think it best for him to stay here for a while . . .”

“Homecoming without anyone coming home is to be the rule this year owing to the epidemic of influenza which has held the campus under quarantine for the past month,” the Emerald reported on October 31. But Campbell felt the crisis had peaked. “President Campbell today issued the following statement to the students: ‘There have been almost no new cases of illness during the past week and there is no evidence to show that the epidemic is not practically over . . . now is the time to redouble every preventative measure and wipe out the sick list entirely. Students wishing to lighten their courses owing to less time in the influenza epidemic will be permitted to do so, even below the 12-hour minimum, without petition, as a result of action taken at a special meeting of the faculty Wednesday afternoon in Guild Hall. It was made clear in the discussion that faculty members intend to be lenient in the matter of making up work missed in the present emergency, and it is desired that every student forced to miss classes feel easy on that point, since everything possible will be done by faculty members for the students’ protection.’”

“Tubbing Frosh Now Taboo,” the Emerald continued, referring to the hazing of freshmen enrolled in the SATC. “An order against all tubbing, blanketing, mill-racing, in the University was issued from the President’s office Saturday night. The order was issued on account of the recent epidemic of influenza as those measures of punishment are considered likely to endanger the health of men.”

Before the influenza outbreak in October, the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton, Washington, had sent six medics to the UO for an internship. Instead of studying, the Emerald reported, “they have given their full time to nursing influenza patients at the two men’s infirmaries on this campus. Walter Bauman, Paul Hamilton, and Arthur Ritter are stationed at the Phi Gamma Delta House infirmary, while Harold Connelly, Max Wilkins, and Boyd Haynes are giving their services at the old Phi Delta Theta house. They have been doing this work for the past three weeks and are attending no classes.” As lucky as the university was to have the sailors on campus, the sailors may have been even luckier. Influenza killed 77 seamen at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard; one of the first to die was Dr. Douglas H. Warner, UO Medical School ’18, on October 8.

On November 5, university registrar A. R. Tiffany announced that “Thanksgiving vacation this year will probably be only one day, Thursday, November 28. Some severe penalty for not attending classes Friday, November 20, will be decided Wednesday.” But on Wednesday, Campbell decided to honor the traditional, four-day Thanksgiving break. In a letter to A. C. Seeley, secretary, State Board of Health, Onthank explained, “We are very anxious to give the students an opportunity for relaxation. Some of the young women have been ill, and many others have been putting in extra time in work in caring for the sick, getting health reports and otherwise doing extra work in connection with the epidemic. The Dean of Women feels that it is highly desirable they be given the opportunity to go home and rest for a few days.”

On November 9, the Register reported that in Eugene, “Epidemic is dying out. Only six new cases reported in three days.” Campbell left for a prearranged 11-day trip to Chicago, and was there on November 11, when World War I ended. Jubilant students thronged in the streets, ignoring university staff members imploring them to continue to observe the influenza ban on public gatherings. The students and Oregon celebrated twin joys: the end of the War to End All Wars, and the apparent end of the deadliest health crisis in US history.

The epidemic had not ended, but was ebbing. The UO still banned gatherings. Then, on November 27, influenza killed Army lieutenant and UO art professor Roswell Dosch, a talented sculptor. Dosch was serving as a bayonet instructor at Reed College in Portland, working on a statuette, The New Earth, a memorial to commemorate the Oregon men who had died in the war, intended for the University of Oregon campus. Prince Lucien and Susan Campbell, who collected Dosch’s art, attended his funeral.

On December 7, Bovard said he could not yet estimate the full financial cost of the epidemic, but that drugs alone cost approximately $600, nursing services cost between $600 and $700, and physicians’ bills totaled $35 a day.

After Christmas break, the UO returned to normal. In 1919, a third, mild wave of the disease continued to sicken people: in early January, history professor R. C. Clark and five members of his family were hospitalized with influenza. By the spring of 1920, the deadly disease disappeared around the globe, as mysteriously as it had appeared. The US Department of Human Services estimates the disease killed 675,000 people in the United States, out of a population of 105 million, including 3,675 deaths in Oregon.

The new university infirmary opened at 1191 University Avenue in January 1919, paid for, in part, by a $2.50 per term increase in student fees, and in part by charging ill students $3.00 a day for all services rendered. In its first six months, 75 students used the infirmary. Its first annual report noted, “The dispensary has located sources of infection in cases of smallpox, measles, etc., and has given the committee the chance to keep the desease (sic) from becoming a general epidemic.”

A century later, headlines in Eugene are reporting eerily similar problems: globally, Ebola has killed thousands in Africa, and threatened to jump international borders; and on the UO campus, an infectious meningococcemia outbreak killed one student and sickened several others. The tools Campbell proactively used to guide the UO through the pandemic in 1918 are relevant today: organization, communication, and caring.

—By Kristine Deacon

Editor’s note: In 1936, the Student Health Service moved into a new building (now the Volcanology Building), which housed a 26-bed infirmary. In 1965, the current University Health Center opened, housing a 40-bed infirmary, isolation wing, and kitchen facility. By 1981, the need for infirmary beds had lessened and the in-patient unit was closed. The University Counseling and Testing Center now occupies the former infirmary space.