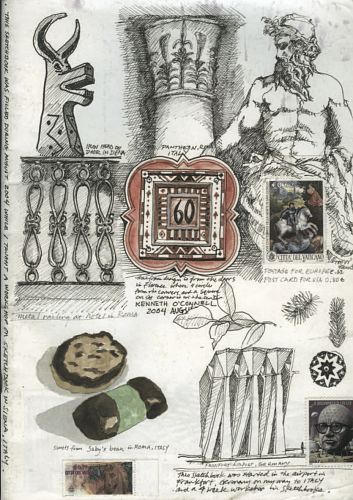

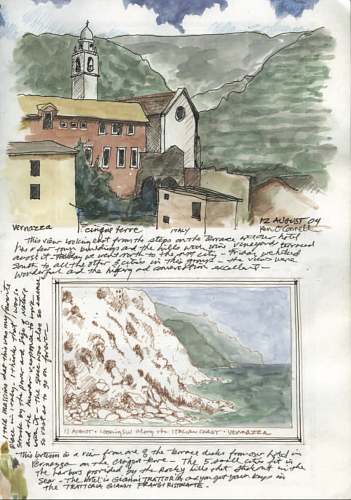

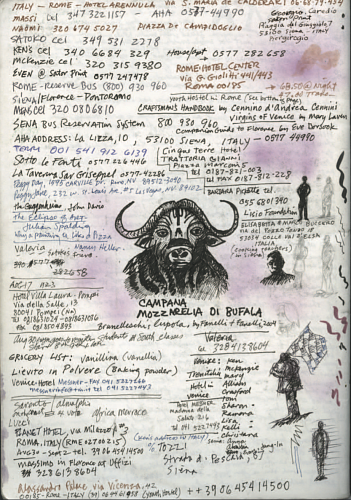

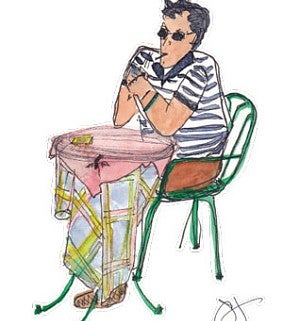

Kenneth O’Connell ’66, MFA ’72, settles into a table at the Pasticceria Anagnina and orders a pastry. Rome is hot in August, and leading a group of American artists on a sketching tour of Italy is hard work. He certainly deserves the treat. The pastry, a buttery, flaky tart with the edges crimped just so, arrives. It is mouth-watering. But before O’Connell picks up his fork, he reaches for a paintbrush. Alternating between sips of espresso and dabs from a tiny, portable palette of paints, he quickly, deftly makes a watercolor sketch of the tart, immortalizing the pastry on page nine of a slim black book. “Before I eat it I always make a sketch of it,” O’Connell says. “When I’ve long since digested and forgotten the flavor of that pastry, I still have that sketch in my sketchbook. The saying that ‘art is long and life is short’ is reinforced by simple things like this.”

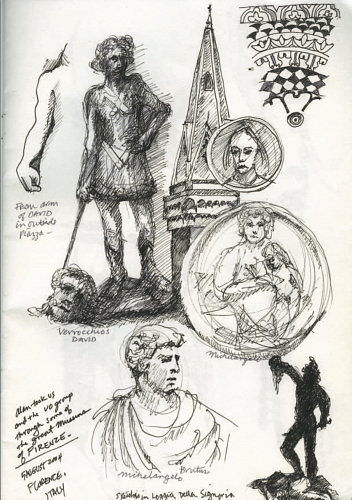

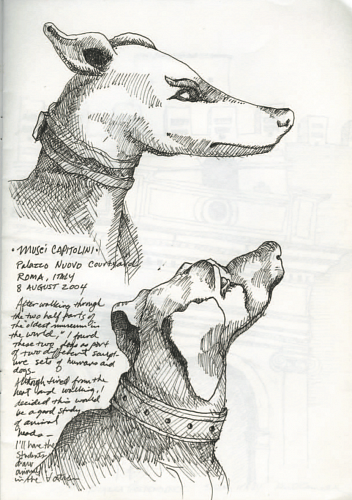

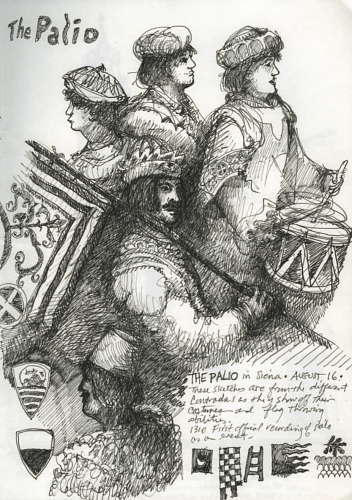

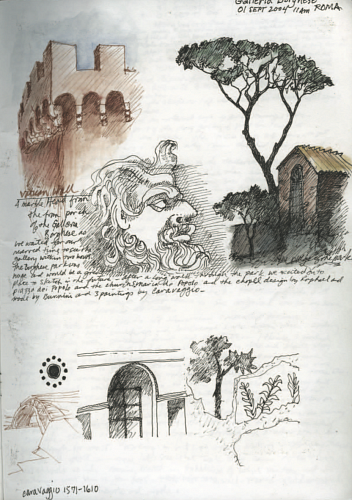

O’Connell is a master at helping his students understand the “simple things” that allow us to focus, understand, and truly participate in an experience, whether that experience is as mundane as eating a tart or as grand as contemplating the Roman skyline. Much of his technique involves breaking down the barriers that intimidate people and prevent them from relaxing into a sketch. “Italy is a great place to visit with sketchbooks because there’s so much to see,” he says—too much for some. He tells these students to focus on fragments. “I’ll say just focus on the door or some of the windows today, don’t worry about trying to draw the whole building, or trying to draw the whole sculpture; just draw the hand, or the arm, or the boot, or the animal in the sculpture.”

O’Connell earned his BS degree from the University of Oregon in 1966 and his MFA in 1972, studying fine art with David Foster. “Dave told me I should number and date my sketchbooks,” says O’Connell, “which I thought was kind of funny.” He took his mentor’s advice, however, and five decades later he is working on Sketchbook 72. (He has them all except number 70, left on a train from Conwy, Wales, to Manchester, England.) He served in the Navy and taught elsewhere for several years before joining the UO faculty in 1978, remaining with the University full time until his retirement in 2002. He taught drawing, painting, ceramics, photography, filmmaking, and animation, always with a focus on visual thinking, and as art department head for thirteen years, he helped bring the department into the digital age.

Although he always had his students keep sketchbooks, the format didn’t emerge as the focal point of his courses until 1999, when he proposed a sketchbook workshop to Randall Koch, director of the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology near Lincoln City and a former student. (“As my late professor David Foster told me,” says O’Connell, “‘Be kind to your students, they may offer you a job.’”) The workshop filled instantly, as did the next, and the next. The Oregon Coast was all well and good for sketching, but some of his students, most of them older adults with the time and inclination to travel, were clamoring for a trip to Italy. Another former student, Lucy Hart ’62, told O’Connell of a school in Umbria where her sister, Lisa Hart Guthrie ’57, had taught for a decade, and in 2006 O’Connell led his first sketchbook workshop in Italy. This summer he will lead his fifth.

The sketchbook, for O’Connell, offers both a window into the thought processes of the artist and an entry point for people who are new to art, helping them to get past the “I’m-not-good-enough” obstacles to drawing that many find intimidating. “I’ve found that people are willing to make a sketch on a napkin or the back of an envelope, but when you give them a nice, $2 sheet of handmade paper, they freeze up. The sketchbook allows them to make mistakes, try things out; they’re given permission to explore.”

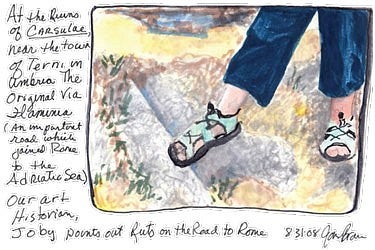

The sketchbook also enables people to see at a level they may never have experienced before. “A sketch, brief as it may be, will last for years in your sketchbook, and lengthen the memory of that place and time and temperature and sound,” says O’Connell. “People remark to me how they have traveled before but they’ve never been able to remember things so vividly as they have from sketching. It makes sense, because drawing is thinking—it causes you to really see, and pay attention, and extract from what you’re seeing elements that you would never notice if you were just glancing at something, or even taking a photograph. Sketching causes you to look at the colors, the shapes of things, to compare sizes and relationships, and suddenly you have a little sketch and it means a great deal to you.”

—By Ann Wiens

Eugene’s “Top Drawers”

Sketching also offers an opportunity to bond with people, says Harrison, even people with whom one doesn’t share a culture or language. “Sharing your sketchbooks in public brings an automatic connection with people. They recognize that you’re paying attention to something they know about, and they care about.”

“I was standing in line at Trader Joe’s, and the woman in front of me [Harrison] was showing the cashier a sketchbook, telling her she’d just been on this sketching trip to Italy,” recalls Jan Brown, an artist and graphic designer. “I asked who the teacher was, and when she said it was Ken O’Connell I was very interested. He had been my instructor at the UO in the late 1970s; he was wonderful!” Brown signed up for O’Connell’s next sketchbook trip to Italy, in 2008. “We sketched our brains out!” she says.

You can see work by Brown, Harrison, and the other Top Drawers online at www.topdrawers.org, and in the exhibition Top Drawers on Tour, on view August 1–31 at the Emerald Art Center in downtown Springfield.

—AW